Why is Japan's WW2 surrender still a sensitive subject?

- Published

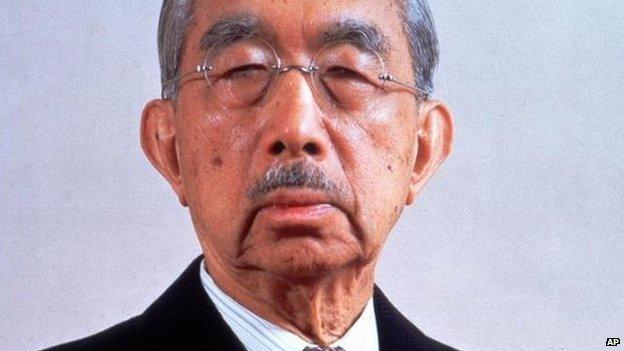

The speech of Emperor Hirohito (seen here in 1982) remains a sensitive topic 70 years on

This Saturday it will be 70 years since Japan's Emperor, Hirohito, publicly accepted the surrender terms of the key Allied countries in World War Two.

It signalled Japan's capitulation and the end not only of the war in the Pacific, but also of Japan's colonial rule of the Korean peninsula, its influence in South East Asia and its attempt to dominate China and the Asian mainland.

With Japan's conservative Prime Minister Shinzo Abe planning to issue an official statement reflecting on the past, this year is a particularly sensitive anniversary.

Progressive critics, inside and outside Japan, worry that Mr Abe's statement may downplay past apologies in favour of a "revisionist" historical interpretation that will antagonise Japan's neighbours, most notably China and South Korea.

How were Hirohito's words received at the time?

Hirohito's remarks that day were unprecedented.

Pre-recorded on a phonograph and delivered in rarefied, classical Japanese, they shocked a Japanese populace, which was unprepared for the possibility of surrender or defeat and had almost certainly never heard their divine head of state speak in public.

The country was still on a war footing.

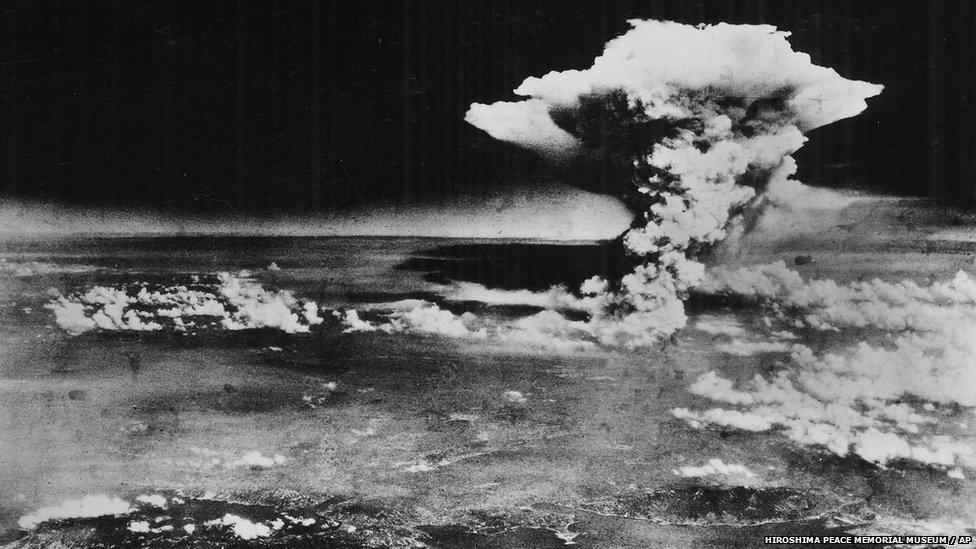

That was despite the near total destruction of Japan's navy by July 1945, a policy of economic strangulation that had imposed massive material hardship on ordinary citizens, the firebombing of major cities, and the atomic devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August.

The cathartic impact of the emperor's words allowed the public to embrace the once alien concept of defeat.

Japan surrendered nine days after the bombing of Hiroshima

The statement was also a necessary means of forcing consensus on a fractious Japanese political and military elite, some of whose members were determined to fight to the last.

Hirohito's acceptance of defeat, which was backed by his senior ministers, almost failed in the face of an abortive coup by young army officers who were trying to stop the imperial broadcast from going ahead.

For an emperor mindful of the impact of America's "new and most cruel bomb", surrender (even if he chose not to use the term) was a means of avoiding the total destruction of Japan and further civilian casualties, and revealingly, the possible "total extinction of human civilisation".

What happened next?

The end of the war prompted jubilant celebrations in Europe and the US.

In Korea it led to a similar outpouring of optimism as Koreans experienced their liberation from 35 years of Japanese colonial rule.

Koreans also saw the brief establishment of a progressive Korean People's Republic in the south of the country.

However, such optimism was short-lived, as US forces intervened to establish an American-led military government in September 1945, while Soviet forces created their own dependent government in the north of a peninsula increasingly divided along geographical and ideological lines.

Ironically, the Americans turned to former Japanese colonial administrators to handle the civilian administration of Korea, a decision that made Koreans deeply sceptical of US intentions, reinforcing the belief (still present to this day) that Korea's interests take second place to those of more powerful states.

What were the consequences for Japan and regional rivalries?

Japan's defeat had profound and in some ways contradictory consequences for the East Asian region and the wider post-war world.

It facilitated a US-led seven-year occupation of Japan that, in its first two years, promoted democratisation and demilitarisation.

Japan established a new identity of anti-militarism, aversion to nuclear weapons and a focus on economic development that ultimately produced the high-speed miracle years of the 1960s.

One of the results of Japan's defeat was a focus on economic and industrial development

More controversially, the continuing occupation, especially from 1948, reflected the onset of the Cold War in East Asia.

US policy makers worried about ideological divisions within Japan, the growing ascendancy of Mao's communist forces in mainland China and the Soviet presence in Japan's "northern territories" (the Kurile islands occupied by the Russians in the closing days of the war and still held by Moscow to this day).

Japan, as America's most important emerging ally in the region, became bound into the strategic and ideological conflict between the communist and Western blocs, but in a manner that, some critics contend, fatally limited its autonomy and policy-making independence.

How has strategic balance in the region changed since then?

From the vantage point of 2015, the 15 August anniversary is a reminder that Japan under Prime Minister Abe is still confronting difficult strategic challenges that echo those of 70 years ago.

These include a Russia that is unwilling to cede territory to Japan, and a still-divided Korean peninsula but one in which North Korea is now a de facto nuclear state and therefore a more threatening power.

Compared to 1945, China is a much more powerful actor able, through its more assertive maritime presence, to challenge the territorial possessions of its neighbours in the South China and (in the case of Japan) East China Seas.

What is the contemporary significance of Hirohito's comments announcing Japan's surrender?

Hirohito characterised Japan's decision to go to war as an attempt to "ensure Japan's self-preservation and the stabilisation of East Asia".

Controversially, he also pointed out that there was no intention "to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark on territorial aggrandisement".

While past Japanese prime ministers have acknowledged the suffering that Japan caused its neighbours during the Pacific War and expressed their "remorse", there are some conservative voices in Japan who identify with the sentiment embodied in Hirohito's August 1945 statement.

The US has asked Mr Abe to avoid inflaming historical tensions

To them, Japan's past actions were neither aggressive nor illegitimate, and they have been lobbying Mr Abe to reflect this alternative interpretation in his own, contemporary statement.

It remains unclear to what extent the prime minister shares these views.

What balance will Mr Abe need to strike?

Given the historical sensitivities involved, any expression of such conservative views would invite condemnation from China and South Korea, as well as from progressive opinion within Japan, at a time when the Abe administration is seeking to pass new legislation to enhance the strategic flexibility of its self-defence forces.

For these reasons, as well as the need to avoid antagonising its US ally, which has called on Japan to avoid inflaming historical tensions, the government is likely to tread carefully.

History, it seems, is anything but an academic matter.

Mr Abe will need to be agile in pursuing a pragmatic foreign policy agenda while maintaining the support of his more conservative allies at home.

Dr John Swenson-Wright is head of the Asia Programme at the Chatham House, external think tank. Chatham House will host the conference The Future of Capitalist Democracy: UK-Japan Perspectives, external on 21-22 September 2015.'

- Published23 July 2014

- Published6 August 2015

- Published6 August 2015

- Published9 August 2015

- Published29 October 2024