Luxury Sri Lanka resort can't hide country's divisions

- Published

Justin Rowlatt reports from a hotel run by the Sri Lankan army

Sri Lanka has everything a holidaymaker could want: a wonderful climate, friendly people, delicious food and beautiful beaches. But some of its resorts hide dark secrets.

The fact that you have to go through a military checkpoint is a warning that the Thalsevana resort is no ordinary hotel.

The troops want to see passports and check the car for cameras. I don't mention that I am a journalist, I know they are not welcome here.

We are waved through security and onto a large military base. There are canteen buildings, long blocks of barracks and mechanical workshops with military vehicles parked in the yard. And armed soldiers milling around everywhere.

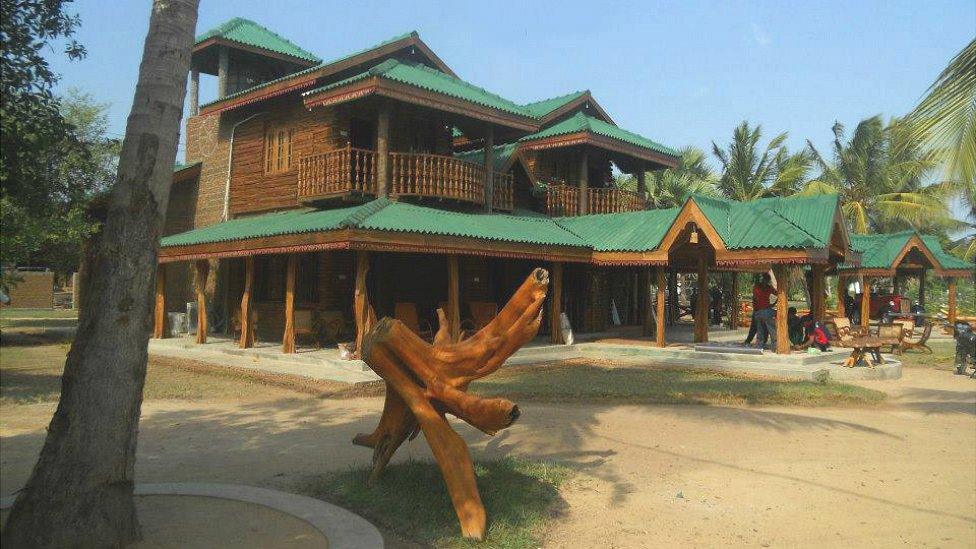

Then, after a short drive, a bizarre sight: a large, luxury hotel.

Children splash in the generous pool. A few yards away stretches a perfect arc of white sand - the hotel's private beach.

Although they don't wear uniforms, many of the staff at the resort are soldiers

I find a free table in the cafe and lean back in the large, comfortable chairs. As the sunlight scissors off the ocean an unusually clean-cut, but slightly uncertain waiter sidles up to the table to take my order.

There's a good reason the waiters have perfect buzz cuts - and appear a little unclear about their role. It is because they - and many of the other staff in the hotel - are actually soldiers.

This dream destination is evidence of the legacy of misery and division that still remains six years after Sri Lanka's civil war ended.

The hotel is owned and run by the Sri Lankan army and the military base it is in is on land seized from Sri Lanka's Tamil minority during the civil war.

Residents of a slum not far away from the resort claim the land it is on belongs to them

Just a few miles down the road, but a world away from the luxury of the hotel, is the slum where some of the people who claim to be the real owners of the land now live.

There are more than 200 people - 58 families - there, but just two water points and a couple of shared latrine buildings.

'Like living in hell'

I met Julius Selvamalar outside her cramped corrugated iron shack. She tells me Sri Lankan troops drove her family from their beachside home on a plot right next to where the Thalsevana now stands.

"We are forced to live like refugees in this slum. It is like living in hell. I had to bring up my children here," she complained.

She told me the land is now very valuable but she doesn't hold out any hope of getting it back.

The army insists, however, that the land was bare when it showed up and erected the hotel. "It is a welfare project of the army for the army personnel," Brig Jayanath Jayaweera tells us.

He says no one has tried to claim ownership of the land. But if they did? "I will have to speak to the commander," he says.

The visible scars of Sri Lanka's civil war may have almost vanished, but deep divisions still remain.

Julius Selvamalar says she has been forced to live in a slum after being evicted from her land

Even in Kilinochchi, once the headquarters of the rebel Tamil Tiger army, there are few signs of the terrible conflict that raged here for more than two decades.

There are new roads and the so-called "Northern Line" railway has been rebuilt.

Yet many human rights abuses have yet to be addressed. Tens of thousands of Sri Lankans are, like Julius, still displaced.

Rajapaksa returns

Finding a long-term solution is a key issue in next week's parliamentary elections.

The current government, under President Maithripala Sirisena, says it wants to devolve power to Tamil regions. That's the option most Tamils support.

But the former president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, is warning that would be a disaster.

I met him in the kitchen of his large home in a suburb of Colombo, the Sri Lankan capital.

He lost power in January, but now he's back, standing as an MP and trying to rally the Sinhalese majority behind his bid to become prime minister.

Tamils are worried what will happen if Mahinda Rajapaksa does well in next week's elections

Mr Rajapaksa told me he was convinced that devolving power could lead to Sri Lanka splitting in two. He said he would do everything in his power to stop that happening.

But he is not popular in Tamil regions. He led the country in the last years of the war, when both sides committed appalling violations of human rights.

Tamil leaders say he did little to address their concerns once the war ended. They are worried what will happen if he does well in next week's elections.

Could conflict resume?

The Tamil National Alliance expects to get the lion's share of the Tamil communities' vote.

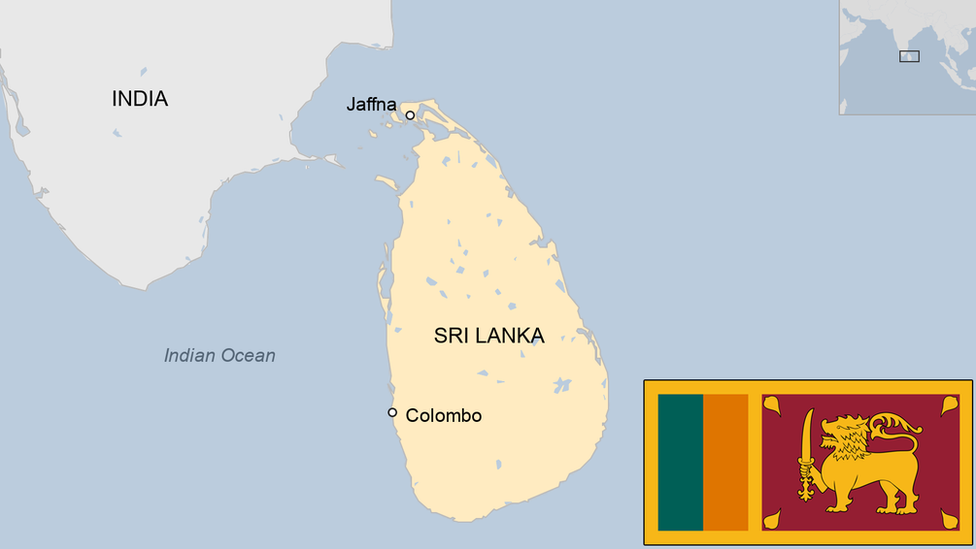

I spoke to the party's spokesman, Suresh Premachandran, in the pretty little garden outside one of the party's offices in Jaffna, the largest city in the predominantly Tamil north of the island.

He told me he thought a return to armed struggle was a real possibility. "Who knows what might happen if Tamils aren't accorded the same rights as other citizens?" he asked.

Is that a threat? "It is not a threat," he said calmly. "Maybe in the future it might be a reality."

That is a frightening thought for a country that is only just beginning to recover from a 26-year-long civil war.

Sri Lankan military's tourist portfolio

The Lagoon's Edge hotel is one of many holiday resorts owned by the Sri Lankan military

If the Thalsevana doesn't appeal, Sri Lanka's military runs a number of other tourist businesses, including:

The exclusive Lagoon's Edge hotel, reserved for senior military personnel and their families. It offers guests the questionable pleasure of enjoying a cocktail as they look out over a stretch of water where thousands of Tamil civilians and soldiers died in the last days of Sri Lanka's bloody civil war

A number of roadside restaurants along the A9 highway that runs to the north of the island

A travel agency, Air Travel Services, which boasts on its website that it is "the latest sphere" of activity for the Sri Lanka army, "after the military victory over the terrorism in North and East"

A whale-watching venture run by the navy and offering tourists the opportunity of an encounter with "the largest living mammals and spinning dolphins in luxury and comfort". But you'll have to wait to get a booking - the service is suspended while the navy's passenger vessel is in dock for maintenance.

- Published10 August 2015

- Published14 August 2015

- Published4 October 2024