Tackling the deadliest day for Japanese teenagers

- Published

The intensity of the competitive school environment is seen as one trigger for teenage suicide

"My school uniform felt so heavy as if I was in armour," said Masa, who was bullied as soon as he started high school.

"I couldn't bear the school's ambience and my heart was pounding. I thought about killing myself, because that would have been easier."

Masa, which is not his real name, had an understanding mother who did not force him to go to school. Otherwise, he wrote for a newspaper for children who refuse to attend school, external, "I would have chosen to kill myself on 1 September when the new semester started".

Masa was not alone in thinking so bleakly in Japan, which has one of the world's highest suicide rates.

Last year, for the first time, the most common cause of death, external of those aged 10 to 19 in Japan was suicide.

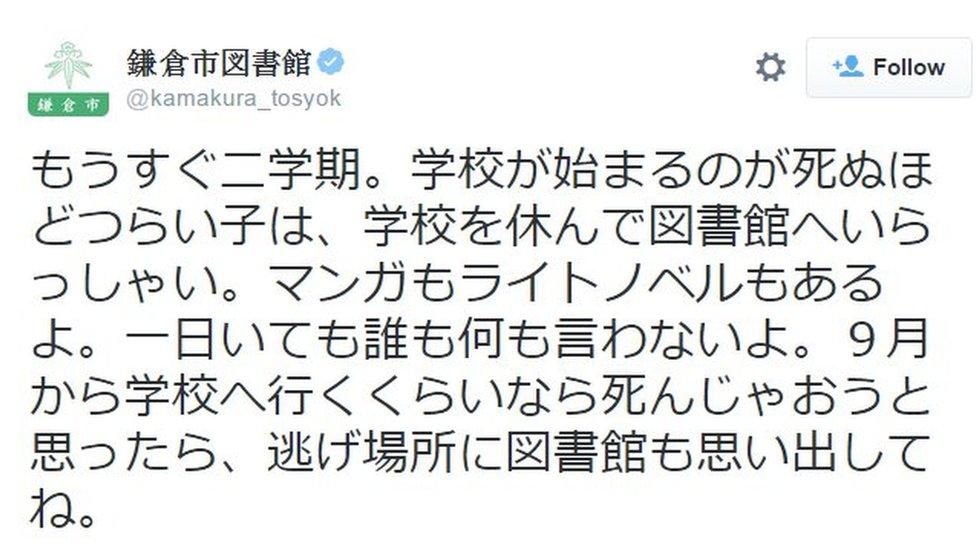

The library's tweet offered itself up as a refuge for students who couldn't face school

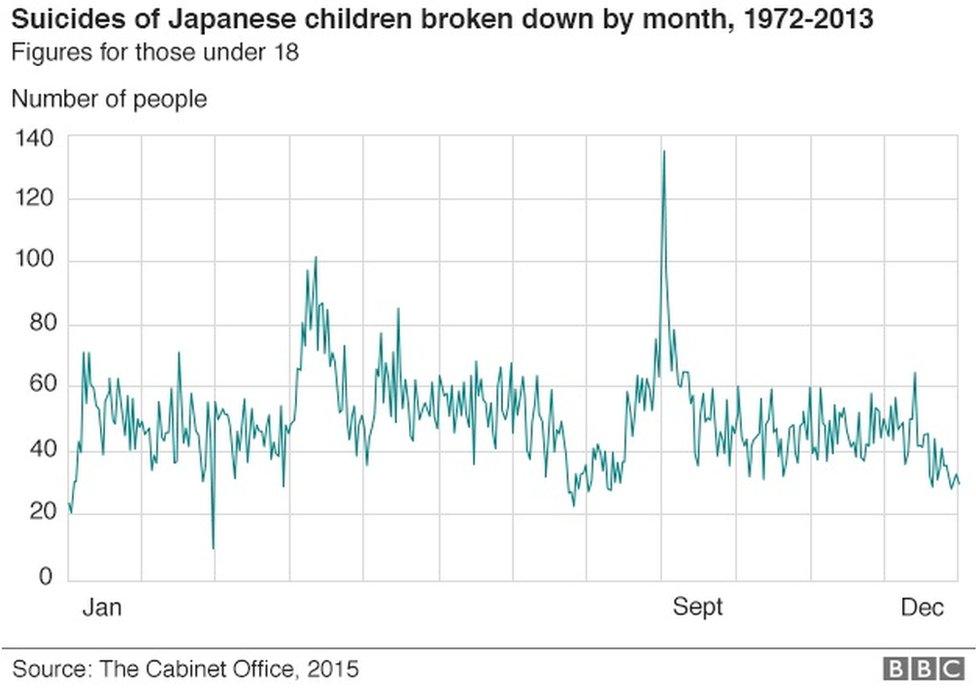

And according to the cabinet office, external, 1 September is historically the day the largest number of children under 18 have taken their own lives.

Between 1972 and 2013, of the 18,048 children who killed themselves, on average 92 did so on 31 August, 131 on 1 September and 94 on 2 September.

The numbers were also high in early April when the first semester begins in the Japanese school calendar.

On seeing the statistic earlier this month, Maho Kawai, a librarian in Kamakura, tweeted: "The second semester is almost upon us. If you are thinking of killing yourself because you hate school so much, why not come to us? We have comics and light novels.

"No-one would tell you off if you spend all day here. Remember us as your refuge if you're thinking of choosing death over school in September."

It was a controversial move for the library, which is part of the city's education committee, not to encourage children to stay in school. The director of the library Takashi Kikuchi told the BBC that there was even talk of deleting the tweet.

But it touched many hearts and within 24 hours, it was retweeted more than 60,000 times.

'Not a choice between school and death'

The high rate of 1 September suicides "was well known in the teachers' community," said Shikoh Ishi, who edits the newspaper for school refusers.

"We started this non-profit organisation 17 years ago because in 1997, we had three shocking incidents involving high school children just before the second semester started.

"Two of them killed themselves on 31 August. Around the same time, three children also set their school on fire and said if it was burnt down, they thought they wouldn't have to go back to class," he added.

"That's when we realised how desperate children were and we wanted to send out a message that it is not a choice between school and death."

The government has set up numerous helplines, external and other systems to support those - not only children - who are suicidal.

But only last week, a 13-year-old boy killed himself on the morning of the opening ceremony of the second semester.

'I hated all the rules'

Mr Ishii himself wrote a suicide note when he was the same age. "At that time, I thought there was no other choice because I didn't know that not going to school was my option," he said.

"I felt helpless because I hated all the rules - not just the school's rules but also the rules among kids. For example, you have to observe the power structure carefully not to get bullied. Even then, if you choose not to join the bullies, you can become their next target."

And the classroom's hierarchy is not as simple as the bully against the bullied. According to the latest government report, external, nearly 90% of the children surveyed said they have both bullied and been bullied.

"Only a few percent of them continue to be one or the other," Mr Ishii explained. "The bigger issue is the competitive society where you have to beat your own friends."

His own experience of being suicidal started when Mr Ishii failed to get into an elite high school. The Japanese term for the entrance exam race includes the word "war" - it is a fierce battle for many Japanese children.

But for Mr Ishii, it was the fact his parents found his suicide note and allowed him to stay at home that saved him.

"I want children to know that you can run away from school," he says, "and things will get better".

If you are in the UK and are affected by this issue there are a range of organisations who can offer support

If you are in Japan these sites and helplines will offer you support , external

- Published3 July 2015

- Published5 July 2013

- Published30 August 2015