Afghan Taliban: Mullah Mansour's battle to be leader

- Published

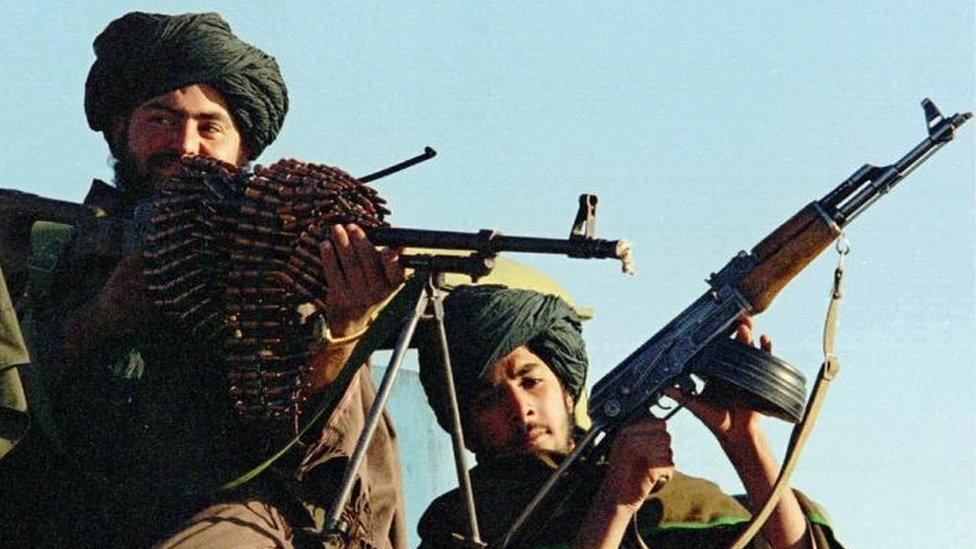

Many Taliban have known no other leader than Mullah Omar - until now

The Afghan Taliban say they have put aside disagreements and rallied around their new leader Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour.

The announcement followed weeks of intensive efforts to unite the movement behind the man who succeeded Taliban founder Mullah Mohammad Omar.

Following the announcement of Omar's death in July, Mullah Mansour was quickly installed as the new Amir ul-Mumineen, Commander of the Faithful.

The decision was initially opposed by some of Mullah Omar's followers.

Mullah Omar (left) died two years ago and his deputy Mullah Mansur swiftly replaced him

Announcement on the Taliban website saying Mullah Omar's family had pledged allegiance to the new leader

The new emir's main challengers were Mullah Omar's brother and eldest son - until now relatively unknown, who questioned the way he was appointed.

But both eventually pledged loyalty to Mullah Mansour.

"Mullah Yaqoub, the son and Mullah Manan, the brother of Mullah Omar, swore their allegiances to the new leader in a splendid ceremony," Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid told the BBC last week, without revealing the location of the gathering.

"Now the movement will continue in a united manner."

In recent weeks, hundreds of Taliban commanders, fighters and clerics travelled in and out of Pakistan to try to overcome the open divisions.

Reports from the Pakistani city of Quetta near the Afghan border said the consultations required local supporters to host hundreds of Taliban in mosques, madrassas and private houses, and organise transport and supplies.

The task of unifying the movement appears as yet incomplete with some senior figures still threatening to disobey Mansour and run their own faction and their own insurgent attacks.

There are reports of deep divisions over the Taliban's new leadership

Drive for unity

The effort put into overcoming the early challenge to Mullah Mansour's leadership suggests how important it was for the movement to preserve unity.

Waheed Mozhda, a Kabul-based expert who used to work in the Taliban foreign ministry before they were driven from power in 2001, says the group realises that unity is key to their survival.

"Their enemies are stronger than they are and therefore they know that if there are differences they will be wiped out," Mr Mozhda says.

Barnett Rubin, a leading US expert on Afghanistan, says the Taliban have been bound together by a coherent ideology that has so far prevented any splits.

"The Taliban were founded to put an end to factionalism and there is a strong presumption against it," says Mr Rubin,

"Everyone follows the commands of the emir. There have been dissident individuals who left or were expelled from the organisation, but once they were expelled or left, they lost all influence."

The BBC spoke to a number of experts on the Taliban to build up a picture of how the group operates under its new leader.

Money from honey: Read our experts' views on how the insurgency funds itself and why its leaders often prefer letters to phones

The BBC's Dawood Azami explains why the militants entered uncharted territory after the death of Mullah Omar

Mullah Omar was a reclusive figure who remained at the head of the Taliban for two years after his death, our obituary explains

Top down

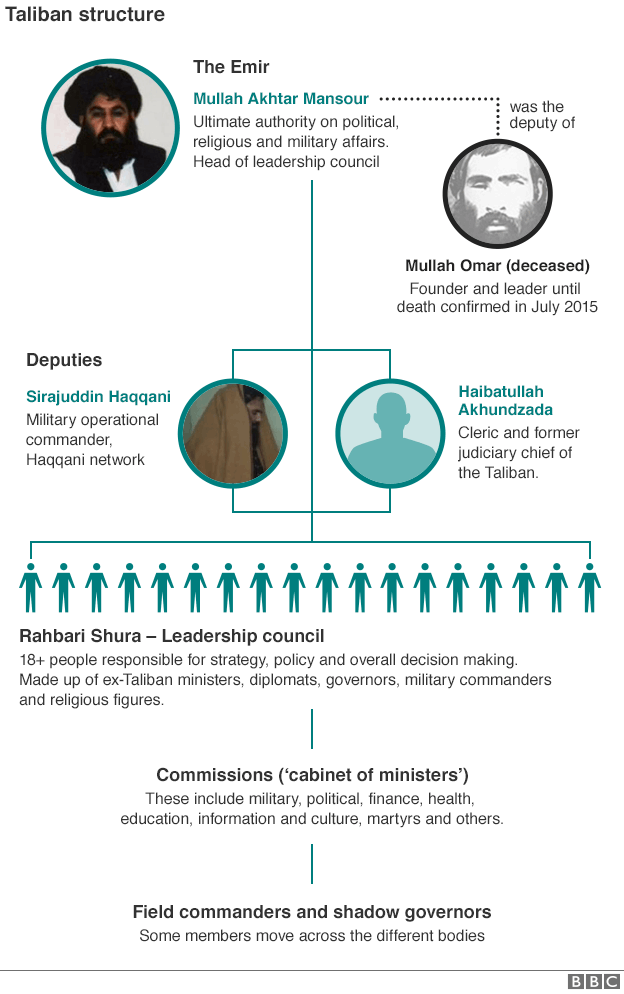

Mullah Mansour as the emir heads a strictly organised command structure with two deputies.

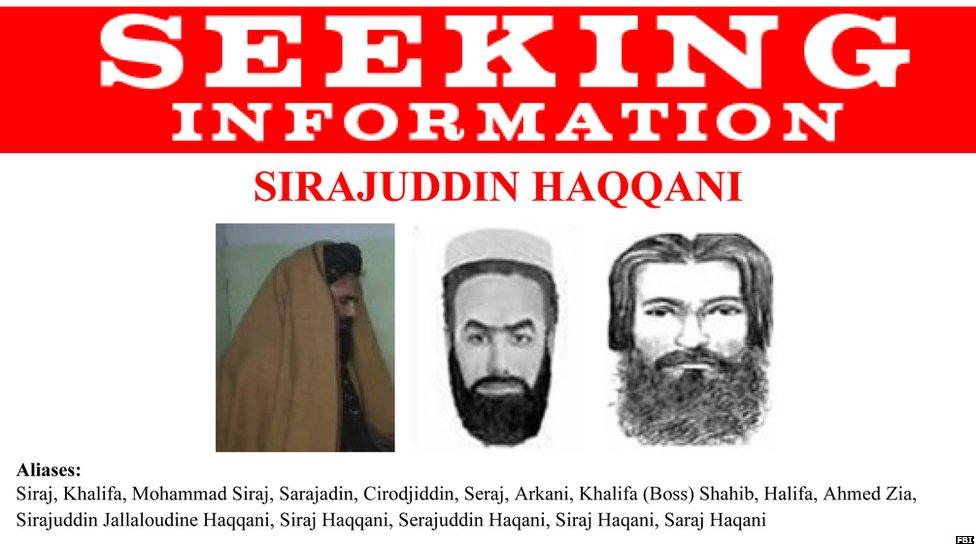

One of these is Sirajuddin Haqqani, a leader of the Haqqani network which has been blamed for some of the most violent attacks inside Afghanistan.

Sirajuddin Haqqani is wanted by the US who have offered a reward of $5m for his arrest.

The layer below is formed by an 18-member leadership council, the Rahbari Shura.

It has just been expanded to 21 under Mullah Mansour, according to the Pakistani writer Rahimullah Yusufzai, who says that the leadership belongs almost entirely to Afghanistan's Pashtun ethnic group.

"Only two members are non-Pashtun, an ethnic Tajik and an ethnic Uzbek from northern Afghanistan," he says. "Besides that an overwhelming majority of the Rahbari Shura members are from the southern provinces of Kandahar, Uruzgan and Helmand, known as the heartland of the Taliban movement and its birthplace."

The leadership council oversees around a dozen commissions - effectively the ministries of the Taliban.

Borhan Osman of the respected Afghanistan Analysts Network, AAN, says the military commission is the most important, running the insurgency.

"The head of the military commission is a person equivalent to a defence minister in a country."

On the ground the insurgency is run by a network of regional commanders and shadow governors in the different provinces of Afghanistan, Mr Osman says.

In parallel to the insurgency, the Taliban run a political commission with an office in Qatar, set up as an international point of contact to facilitate initial peace talks.

Who is Mullah Mansour?

Long seen as acting head of the Taliban, and close to its founder Mullah Omar

Born in the 1960s, in Kandahar province, where he later served as shadow governor after the Taliban's fall

Was civil aviation minister during the Taliban's rule in Afghanistan

Had an active role in drug trafficking, according to the UN

Has clashed with Abdul Qayum Zakir, a senior military commander, amid a power struggle and differences over negotiations with the Afghan government

A man claiming to be Mansour met former Afghan President Hamid Karzai for peace talks in 2010 - but it later emerged he was an imposter, external

Secret communications

With the leadership thought to be based in Pakistan and commanders and fighting units scattered over many different Afghan provinces, communication is a major challenge,

BBC Urdu's Islamabad bureau editor, Haroon Rashid, says the main consideration is keeping sensitive information safe.

"The best and safest option for them is through 'word of mouth'," he says. "But they have also been communicating through written letters. I have seen some letters in North Waziristan's main town of Miranshah which suggests that written letters were the most popular way of communicating."

Borhan Osman says field commanders and shadow governors will use electronic methods too.

"While the provincial governor may not be himself talking to one of his commanders, one of his aides might do it, using all this code language, maybe talking on the phone and also increasingly now on walkie-talkies when they are close by in the same area."

Some of the names used for the Taliban leadership council, such as the "Quetta Shura" suggest a firm base in a specific location, but Borhan Osman says such terms are misleading.

"It's a name for a mechanism rather than for a headquarters," he says. "They meet at the home of one of the members or supporters. The next day they meet in another town."

Haroon Rashid agrees that it would be wrong to think of the Taliban as an organisation with a firm infrastructure.

"They survive on the bare minimum," he says. "They remain on the move all the time. Pakistani seminaries and mosques have remained their favourite place to operate from."

Mullah Omar dead: What we know, in 1 minute

Money from honey

The Taliban have traditionally relied on donations from sympathisers in the Gulf.

But some experts say that such "foreign aid" has dwindled.

"I have the impression that this source has decreased as the focus of global jihad is now back in the Arab world itself," says Barnett Rubin. "Inside Afghanistan the main income seems to come from protection rackets and tolls, bribes or taxes collected or extorted from commercial and other traffic."

Mr Rubin says that some Taliban also own businesses in the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

"The Haqqanis have a large business network in Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Persian Gulf, including the sale of honey. And of course everyone in Afghanistan who controls land that grows poppy or roads over which opiates are transported makes money from protection and extortion of the drug industry."

The potential of Afghanistan's national resources has also not been lost on the Taliban. The ex-Taliban official Waheed Mozhda says that the group added a special branch to its finance committee to deal with mining just last year.

"The committee leases those mines under the Taliban's control to people and companies," he says.

The Afghan Taliban have been fighting for more than 20 years and make money from many sources

Pakistan connection

The Afghan government consistently claims that its neighbour Pakistan is supporting the Afghan Taliban, something Islamabad rejects.

"Pakistan officially denies it has any control whatsoever over the Afghan Taliban," says Haroon Rashid. "But there is hardly any denying the fact that Pakistan has influence on them and has contacts."

Barnett Rubin says that claims the Pakistani security services, the ISI, have close connections have some credibility.

"It is quite possible that many Taliban operations are directly run by ISI or ISI contractors embedded with the Taliban," he says. "This was the case during 1994-2001."

Mr Rubin says that Pakistan may use the Taliban to further its strategic interests in Afghanistan:

"Pakistan wants to use the pressure of Taliban operations in Afghanistan to prevent consolidation of a pro-Indian or pro-Pashtunistan government. They have said so. But implicitly they are offering to stop the Taliban insurgency if those demands are met."

The Pakistani Taliban are thought to back Mansour although support is largely symbolic

Allies and rivals

Pakistan of course has its own insurgency to deal with at home, the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), as well as al-Qaeda affiliated groups.

Observers say that while links to the Afghan Taliban exist, this amounts to little practical co-operation.

"The TTP has pledged allegiance to Mullah Omar and by default [they] would be transferring that allegiance to Akhtar Mansour," according to the AAN's Borhan Osman.

"But even from the beginning it was more of a symbolic solidarity. The TTP is a completely different organisation, with a different ideology, different goals, different mechanisms. It's the same as with al-Qaeda. It pledged allegiance to the Taliban, but that is just symbolic solidarity."

One potential rival to the Afghan Taliban has emerged with some insurgents in Afghanistan declaring allegiance to the Islamic State group which claims a presence in some parts of the country. But observers say these are mainly disgruntled fighters.

"Some Taliban with grievances against the leadership and who found it impossible to organise factions, instead left the organisation and joined IS," says Barnett Rubin.

There are still some challengers to the new emir's authority.

One prominent field commander in southern Afghanistan, Mullah Mansour Dadullah has accused the new leader of being a puppet of the Pakistani intelligence service and there have been reports of clashes between his supporters and mainstream Taliban fighters.

But despite these challenges, the AAN's Borhan Osman thinks there is no sign that the Taliban are seriously weakening.

"The fight is going [on] as intensive as ever. So we don't see any changes on the ground, so far at least."