Why is Nepal's new constitution controversial?

- Published

The constitution sparked protests and rallies across Nepal

Nepal is on the cusp of adopting a new constitution. It potentially ends a saga that began shortly after the end of the Maoist war in 2006.

But while many are happy that the new republic now has the much-heralded document, some, for varying reasons, remain deeply unhappy with it - and its birth-pangs have been violent. At least 40 people have died in clashes linked to the constitution.

How did the new constitution come about?

Maoist rebels waged a 10-year civil war until a peace deal was reached

The demand for a new constitution was raised by Maoists rebels, who waged a 10-year civil war which ended with a 2006 peace deal. The Maoists won elections to a constituent assembly two years later, leading to the abolition of the 240-year-old monarchy. But because of squabbles, the assembly failed to draw up a new constitution.

A new assembly elected in 2013 is once more dominated by the traditional parties. They and the Maoists, working together, pushed through the new draft charter in June, saying the disastrous earthquakes in April and May had concentrated their will to get it done.

Over the past few days assembly members have passed all its articles and the document is to be enacted on Sunday.

Nepal's politicians celebrated after the new constitution was approved in parliament

What does the new constitution say?

The new republic will become a federal one. The Maoists' proposal of federalism was later adopted by many more mainstream parties because of the diversity of Nepal. Its people speak over 100 languages. They're split by divisions such as high- and low-caste, Nepali-speaking v speakers of indigenous languages, hill ethnicities v lowland ethnicities, and gender divisions, with high-caste men from the hills almost supremely dominant up to now.

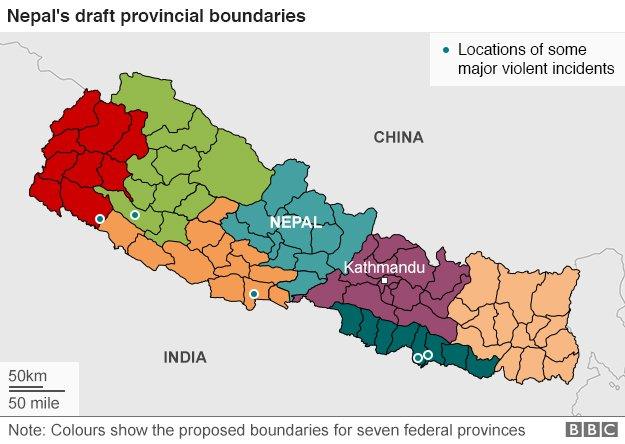

The new document has drawn up provisional boundaries for seven states but their names are to be decided by their eventual assemblies and a commission has yet to fix their final boundaries. Nepali society has become deeply polarised on whether the states should be ethnically delineated.

At least 40 people have died in clashes at protests over the draft constitution. Some of the most violent incidents include (from left to right):

Tikapur, Kailali district: Clashes kill 8 police officers and a child, 24 August

Birendranagar, Surkhet district: Three protestors were shot dead by police, 10 April

Bethari, Rupandehi district: Four killed in police firing including a four year old boy and a 14 year old girl, 15 September

Jaleshwar, Mahottari district: Three protesters shot dead by police on 9 September; one police officer killed on 11 September

Janakpur, Dhanusa district: Three protesters killed in police firing, 11 September

Why are some ethnic groups unhappy?

Many members of traditionally marginalised groups fear that the constitution will still work against them as it's been rushed through by established parties which - including the Maoists - are dominated by high-caste, mostly male, leaders.

One grievance is that a smaller percentage of parliament will now be elected by proportional representation - 45%, compared with 58% under the previous post-war interim constitution. The PR system has helped more members of indigenous and low-caste groups, historically repressed and marginalised, get elected.

Tharu activists have rallied against the proposed federal states

Some ethnic communities are unhappy at the proposed boundaries of the new provinces, although these may be subject to change. This disquiet has been especially intense in the Terai - Nepal's long southern lowland strip bordering India, where recent years have seen tensions between lowlanders and highlanders who have migrated there over recent decades.

In the western Terai one lowland group, the indigenous Tharus, are unhappy at the prospect of being split in two and forced to share their provinces with hill districts that they fear will predominate.

Who else is unhappy?

Activists at a rally demanding women's rights in the constitution

Women's groups and campaigners on women's issues say the new constitution discriminates against Nepalese women in what is already a patriarchal society. According to the Kathmandu Post, external, under the new constitution it will be difficult for a single mother to pass her citizenship to her child.

And if a Nepali woman marries a foreign man, their children cannot become Nepali unless the man first takes Nepali citizenship; whereas if the father is Nepali, his children can also be Nepali regardless of the wife's nationality.

In eastern Terai the so-called Madhesi communities, ethnically and socially close to Indians just across the border, complain they have always faced discrimination and lack of acceptance by the Nepalese state. They say the above citizenship measures will disproportionately affect them because there are many cross-border marriages.

Madhesi groups say citizenship measures will discriminate against them

On the more conservative side, Hindu groups that want the restoration of the country's officially Hindu status (abolished nine years ago) are not happy.

The new draft enshrines secularism - although it is a moderate secularism, which says the state is responsible for protecting ancient religious practices, and also makes the cow, sacred to Hindus, the national animal.

Those who favour strong devolution say the new provinces will have fewer powers than originally envisaged - for instance their autonomy on provincial laws, banking and foreign aid will be limited.

Hindu activists have demanded the constitution declare Nepal a Hindu state

Many campaigners for change complain that this new draft was rushed through, with only token and brief public consultations, overseen by the security forces.

And some of those who fought for the Maoists, or supported their aims in their guerrilla war, or who saw them as the most progressive post-war party, now accuse the leftists of betrayal and wonder why the war was fought. In their original charter the Maoists vowed among other things to end patriarchy, let ethnic minorities form their own governments, and redistribute land from large holders to the landless.

Who is happy?

Supporters of the new constitution gathered to celebrate on Thursday

Very many Nepalis are simply relieved that the country has a new constitution after seven years of wrangling. "Now that we have a constitution let us hope there will be rule of law," wrote one woman on Facebook. "As the country stabilises and starts moving towards development, there will always be possibilities of unfavourable laws to be amended."

Some see the document as progressive as it provides for quotas for some groups, including women, indigenous communities and low-caste Dalits, in serving on constitutional bodies.

One notable social group praising the new document is the Blue Diamond Society, which has successfully campaigned for rights of sexual minorities including transgender, gay, lesbian and bisexual people. Its leader, Sunil Pant, who was a member of the first Constituent Assembly, has praised articles that list "gender and sexual minority people" as disadvantaged and that enshrine their right to participate in state mechanisms.

What of the future?

Nepalese youth staged a flower rally to welcome the new constitution

Some say this constitution is not the way forward and may spur further violence.

One Madhesi leader, Shivaji Yadav of the Federal Socialist Forum, has alleged that "the big parties have tried to crush the minority groups" and "pushed the nation into chaos". He says the constitution has been rushed through for the sake of the privileged old guard of politicians, not "the people".

A similar warning has come from Bhoj Raj Pokhrel, a former national election commissioner. He said the "rushed" constitution was leading to conflict, and the state must immediately address the grievances of those opposing it; the country's future depended on it.

But senior politicians are hailing the document. The foreign minister, Mahendra Bahadur Pandey, said Nepal's people "have achieved a republican nation that they have aspired for for decades".

The Maoists' leader, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, called the adoption of the constitution "a victory of the dreams of the thousands of martyrs and disappeared fighters".