Frozen child: The youngest person to be cryogenically preserved

- Published

Matheryn Naovaratpong is the youngest child to be preserved in this way

Earlier this year, a two-year-old Thai girl became the youngest person to be cryogenically frozen, preserving her brain moments after death in the hope that she will one day be brought back to life. The BBC's Jonathan Head visited her family outside Bangkok to ask why they chose to grieve this way.

The room where Matheryn Naovaratpong spent the last few months of her life is bare and white, furnished only with the drip-stand that helped sustain her, and her cot, also white. The only splash of colour in this austere setting comes from a small gold Buddhist statue, a few favourite stuffed toys, and a huge portrait of the little girl on the wall.

It has the feel of a shrine to a young life tragically cut short. Matheryin, or Einz as her family nicknamed her, developed a rare form of brain cancer just after her second birthday. She died on 8 January 2015, just before she turned three.

But by then her parents, both medical engineers, had made a decision that they hope may give Einz another chance of life.

Sahatorn and Nareerat Naovaratpong say they firmly believe Einz will live again in the future

"The first day Einz was sick, this idea came to my mind right away that we should do something scientifically for her, as much as is humanly possible at present," says her father, Sahatorn. "I felt a real conflict in my heart about this idea, but I also needed to hold onto it. So I explained my idea to my family."

That idea was to preserve Einz through technology known as cryonics. The body, or in Einz's case just her brain, is put into a deeply frozen state at the point of death, and kept that way until, at some point in the future, extraordinary advances in medical technology allow her to be revived, and for a new body to be created for her.

"As scientists we are 100% confident this will happen one day - we just don't know when," he said. "In the past we might have thought it would take 400 to 500 years, but right now we can imagine it might be possible in just 30 years."

'This will happen one day'

At first Sahatorn said it was difficult for the rest of the family to accept this idea, but as Einz's health deteriorated, they came round.

Einz lived for much of her short life in hospital in Bangkok

"Matheryn had something special about her from the day she was born," he says. "She communicated with her love more than the other children, always wanting to be part of our activities."

Sahatorn and his wife Nareerat have three other children. Nareerat had to have her uterus removed after the first birth, so Einz and her younger brother and sister were conceived through IVF. Technology, they say, played a central role at the very start of her life, and could well help restore it.

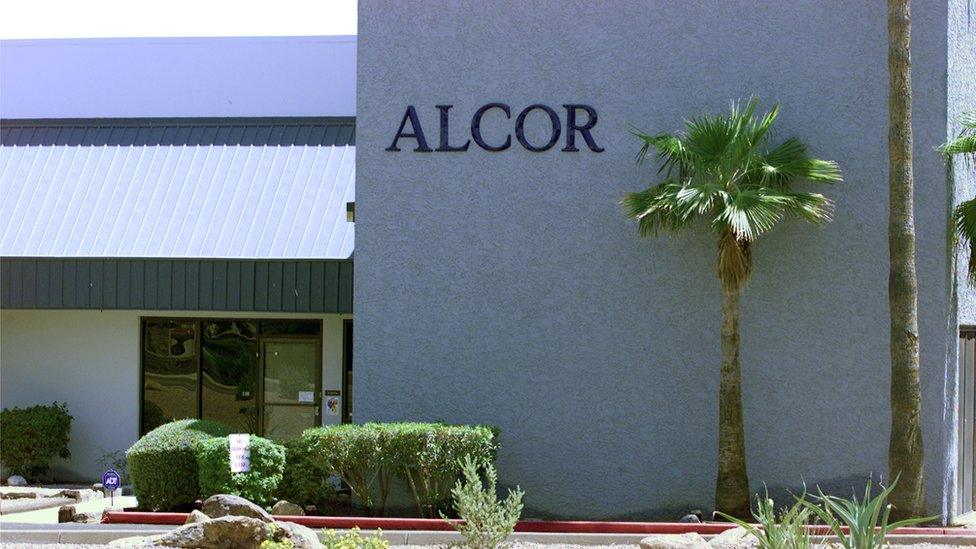

The Naovaratpong family chose Alcor, an Arizona-based non-profit organisation that is the leading provider of what it calls "life extension" services, to carry out the preservation of Einz's brain. The family was closely involved in the preparations, designing the special coffin in which she would be transported to the United States.

A standby team from Alcor flew to Thailand to supervise the initial cooling of the body. As the little girl deteriorated, she was moved from hospital to her own room. The moment she was pronounced dead, the Alcor team begin what is known as "cryoprotection"; removing bodily fluids and replacing them with forms of anti-freeze that allow the body to be deep frozen without suffering large-scale tissue damage.

After arriving in Arizona her brain was extracted, and is preserved at a temperature of -196C. She is Alcor's 134th patient, and by far its youngest.

A personality preserved

Sahatorn's description of the procedure sounds like the stuff of science fiction, even brutally clinical, when you remember this was after all the moment of loss of a much-loved daughter. But the family are very clear about their feelings.

The parents say it was their love for Einz that drove them to try to preserve her

"I tell you we still feel our love for her. Although we fought to be strong, when she had passed away, we were no different from other families; we cried every day. We still need time to heal."

In his mind, Einz's thoughts and personality are preserved with her brain at Alcor, and may at some stage be enough for her life to be reconstructed. He and his wife also plan to have their own bodies preserved cryogenically, although he acknowledges there is little chance they will be able to meet Einz again in their new lives.

They also plan to visit the Alcor facility, to see the steel container in which Einz's brain is being kept in what the company calls "biostasis". The Naovaratpongs say they have donated similar sums of money to what they have spent on Einz's cryopreservation to cancer research in Thailand.

The science of putting off death

Alcor says its operation is "an experiment in the most literal sense of the word". It does not promise a second chance at life, but says cryonics is "an effort to save lives".

It says "real death" only occurs when a dying body begins to shut down and its chemicals become so "disorganised" that medical technology cannot restore them. Future technology could make it more likely that the process can be reversed.

Moments after a customer is declared legally dead, the body is put on artificial life support, and blood replaced with preservatives, for transportation from anywhere in the world to Alcor's headquarters.

The body is flooded with chemicals called "cryoprotectants", which cool cells to -120C without ice forming, a process called vitrification.

The body is then cooled further to -196C and stored indefinitely in liquid nitrogen.

And what of the future? That time, possibly long after their deaths, when technology might allow Einz to live again? The family is collecting pictures and recordings from her life and theirs, so that she will know something of her previous life. Alcor, in its contract with them, promises to supervise a careful re-entry into life for its patients.

This doubtless makes uncomfortable reading for many people. It may not be easy understanding or accepting the reasoning given by the family for taking this path. You cannot help wondering whether this is just a way of avoiding the enormous grief of losing such a young child, or wondering how valid Alcor's pledges are for something that may not be possible for decades, even centuries.

Yet Sahatorn and Nareera clearly are grieving, while at the same time holding out hope for a future most of us cannot imagine yet, in which Einz will live again. They have thought very deeply about it, and feel comfortable with what they have done.

"It was our love for her that pushed us towards this dream of science", says Sahatorn. "Surely our society is moving towards a new kind of thinking that can accept this."