Kyrgyzstan's elections: Six things to know

- Published

An election poster in Ala-Too village about 30 km from the capital Bishkek. Most Kyrgyz voters live in rural areas

Voters in the mountainous central Asian republic of Kyrgyzstan will elect a new parliament on 4 October in a poll markedly different from those in other ex-Soviet states in the region.

The other central Asian countries are run by all-powerful presidents, some of whom have been in office since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Kyrgyzstan by contrast is viewed as the most pluralist and politically open country in the region.

Two presidents who were seen as corrupt and authoritarian have been deposed in uprisings, and in 2010 a new constitution handed more powers to parliament.

Here are six things you need to know about the polls, in a country dubbed as Central Asia's "democratic experiment".

Sweeping up before election day at a polling station in the village of Tash-Moynok near Bishkek

1. Drama and betrayal (also known as multi-party politics)

While its bigger neighbours only offer a handful of pro-president parties, Kyrgyzstan has 14 parties competing for seats in the 120-member parliament, the Jogorku Kenesh - a number already whittled down from an initial 34 applying to take part.

"The other [states] are authoritarian and party politics really don't matter," says John MacLeod, a Central Asia expert at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR).

But in Kyrgyzstan's last election in 2010, five parties made it into the parliament, forming a variety of alliances and coalitions over the following five years.

As a result, the Jogorku Kenesh is a lively place, especially when compared with the rubber stamp parliaments of Kyrgyzstan's neighbours.

Observers say that the choice before the electorate is both familiar and confusing.

While many candidates are veteran politicians who have been on the scene for years, they are often changing allegiances, with former allies falling out and ex-rivals forming new coalitions.

A Kyrgyz boy holds a party flag at a campaign event in a stadium in Belovodskoye

2. Money and crime

All parties taking part need to comply with quotas for female candidates, national minorities, young politicians and persons with disabilities on their party lists.

Despite this, many of the candidates are rich businessmen.

This is because there is no state-funding for parties, so if you want to stand and stand a chance, you need to be able to finance a campaign in Kyrgyzstan's noisy political scene.

There have also been several cases of candidates being disqualified for having a criminal record.

The campaign has been fraught at times. Activists have torn down rival election posters, and with just days to go, a prominent opposition leader was disqualified over an alleged physical attack on a rival candidate.

Fourteen parties are taking part in the parliamentary poll

Voters lists have been compiled using biometric data for verification at each polling station

3. Back to the future

Expect plenty of the classic felt hats, or kalpaks, on display as voters queue up to cast their ballot.

But Kyrgyzstan is also making a big leap into the future, using finger print scanners to verify voters, and ballot scanners for an initial automated vote count at polling stations.

It's the first time biometric voting technology will be used in the region.

The authorities hope to combat fraud, but there are concerns that the year-long effort to collect everyone's biometric data has not been complete.

The OSCE, a pan-European body which has sent observers to watch the poll, says some citizens have not been registered "because they live in remote locations, lack interest or are unwilling to provide biometric data due to concerns about the use and protection of personal data".

Casting their vote will be a particular problem for the estimated several hundred thousand Kyrgyz working as migrant labourers abroad, mainly in Russia. Many have not had their biometric details registered, and may not be able to travel to voting centres.

Another worry is that technology might fail on the day and spark voter frustration, a concern in a country prone to spontaneous protests.

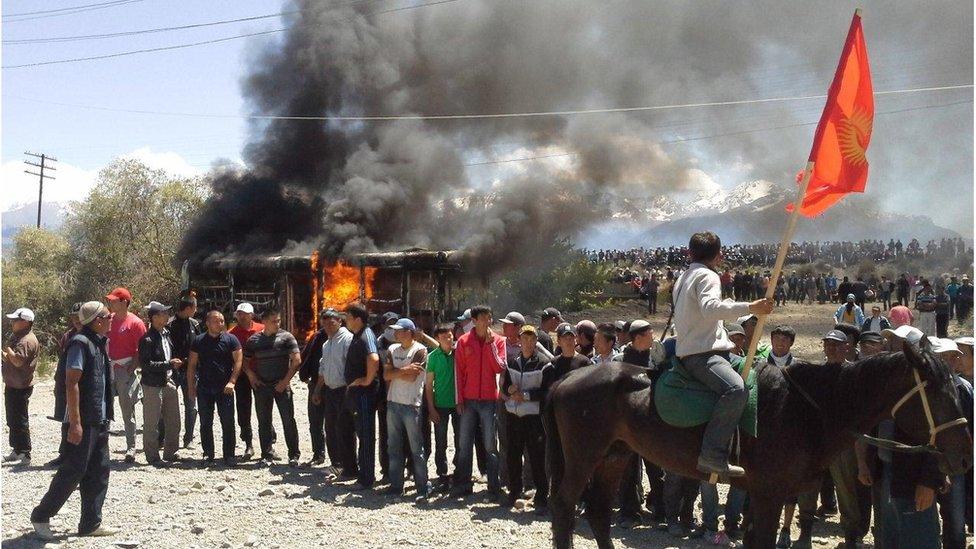

There have been dozens of protests demanding the nationalising of the country's biggest gold mine

4. Debating gold and corruption - but no ideology please

What is the Kyrgyz parliament actually doing?

One of its big obsessions has been the country's biggest gold mine, Kumtor, a major contributor to the economy.

There have been dozens of debates about the mine's environmental impact, the profit sharing deal with the Canadian co-owners and above all whether the mine should be nationalised.

Corruption is another constant topic for debate.

President Almazbek Atambayev's supporters defend his record in clamping down on fraud and bribery, but opposition parties say the government is only targeting its opponents.

What the debates lack are clear ideological lines between left and right.

"The political parties are not so much the carriers of ideas as the vehicles for political ambition, personal interests, business interests, even regional interests", says the IWPR's John MacLeod. "So there is a lot of pushing and shoving."

Kyrgyz politicians agree on tighter regulation of religious groups amidst fears of rising extremism in the majority Muslim country

5. Polygamy as a party policy

The election monitoring group, Coalition for Democracy and Civil Society tried to pin down the parties' various political programmes.

It submitted a list of policy questions to all parties so voters could figure out what each stands for.

While not entirely scientific - just eight parties replied for example - there were some interesting insights.

There were areas of broad unanimity, including support for increased regulation of religious groups (reflecting regional worries about extremism), and a big thumbs down for austerity.

Parties were divided over whether the fight against corruption had been handled well, or the need for sexual health education in schools.

On one of the more unusual policy points, a single party answered yes to the question of whether polygamy should be legalised.

Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev with his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin at a regional summit

6. More Russia, less US

Foreign policy seems to be one area of cross-party agreement with a majority of parties prioritising relations with Russia over ties with the United States.

Given that Kyrgyzstan has just joined the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union, that's hardly a surprise.

Mr MacLeod says "there's not an awful lot of interest" in the polls from Western countries, "because the perception is that Kyrgyzstan is 'lost' or has become more of a Russian satellite".

On the plus side, it is likely that the polls "will go roughly ok" and the country will end up with "a diverse, pluralist kind of system, dominated of course by personal interests", he adds.