Afghan conflict: What we know about Kunduz hospital bombing

- Published

International charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) has demanded an independent international investigation into the US bombing of its hospital in the city of Kunduz in northern Afghanistan.

At least 30 people, including MSF staff, were killed in the early morning attack of 3 October. MSF says dozens were injured and the hospital severely damaged.

The US in November 2015 said that the crew of a warplane that attacked the hospital misidentified it - believing it to be a government compound taken over by the Taliban.

What happened?

In the early morning of 3 October, a US AC-130 gunship conducted an air strike on what crew members thought was a Taliban compound.

US officials have blamed malfunctioning electronics and human error for the targeting mistake.

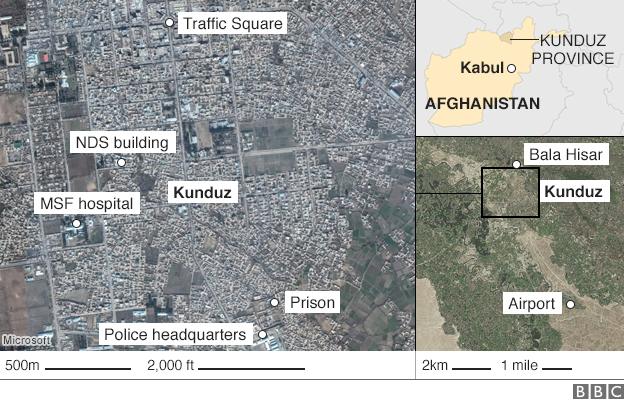

An investigation by the US in November 2015 said that the crew of the AC-130 gunship relied on a physical description of the compound provided by Afghan forces. It was this which led the crew to attack the wrong hospital, which was about 410m (1345ft) away from the intended target.

Gen John Campbell primarily blamed human error for the attack

Who is saying what?

The US military and MSF have differing accounts of the barrage, including the duration and the attempts made to stop it.

The military claims that the strike lasted for approximately 29 minutes, and ended before commanders realised a mistake had been made - despite a call from MSF urging an end to the firing 12 minutes into the attack.

The charity says that the firing lasted for nearly an hour, and desperate phone calls asking the military to stop firing were still being made about 20 minutes after the military says the assault ended.

MSF says the warring sides were well aware of the hospital's location in Kunduz, and have described the attack as a war crime and a black day, external in its history.

In a review released in early November, external, the charity said there were no weapons or fighting inside the compound in Kunduz before the bombing started.

The report said hospital staff were shot at from the air while fleeing the premises.

The BBC has gained exclusive footage from inside the MSF hospital in Kunduz

The US investigators said they found no evidence that the aircraft crew or US Special Forces on the ground knew the targeted compound was a hospital at the time of the attack.

The Afghan defence ministry said "armed terrorists" were using the hospital "as a position to target Afghan forces and civilians".

But MSF has denied this: "Not a single member of our staff reported any fighting inside the hospital compound prior to the US air strike on Saturday morning."

The US military's explanation for the incident has been muddied because it has changed its account of how the air strike came about.

Statements initially said US forces had come under fire, but then said air strikes were requested by Afghan forces under Taliban fire.

The US military chief in Afghanistan Gen John Campbell admitted in October 2015 that "the decision to provide aerial fires was a US decision, made within the US chain of command".

In November, he said that the US had "learned from this terrible incident," and that officials would be taking "administrative and disciplinary action through a process that is fair and thorough (and) considers the available evidence."

"I saw doctors and patients burning" - survivors speak to the BBC's Shaimaa Khalil

What does MSF want to happen now?

MSF says that statements from the Afghan and US forces imply they worked together to deliberately target the hospital - and amount to an admission of a war crime.

The organisation's president Joanne Liu said they "cannot rely on internal military investigations by the US, Nato and Afghan forces".

She has called on the International Humanitarian Fact-Finding Commission (IHFFC), external - a never-used body established in 1991 under the Geneva Conventions - to investigate.

The IHFFC is "the only permanent body set up specifically to investigate violations of international humanitarian law", Ms Liu said,, external and she called on the commission's signatory states to activate an inquiry.

However, according to the IHFFC provisions, an inquiry needs the specific endorsement of the parties to the conflict.

Neither the US nor Afghanistan is a signatory, and therefore they would have to issue separate declarations of consent to the investigation of the Kunduz bombing.

After details of the November 2015 US military investigation were released, MSF reiterated its calls for "an independent and impartial investigation into the attack," and said the errors detailed in the investigation illustrate "gross negligence on the part of US forces and violations of the rules of war".

What constitutes a war crime?

War crimes are acts that constitute a grave breach of the laws of war. At the heart of the concept is the idea that an individual can be held responsible for the actions of a country or that nation's soldiers.

According to the International Criminal Court (ICC), external, war crimes can include:

murder

mutilation, cruel treatment and torture

taking of hostages

intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population

intentionally directing attacks against buildings dedicated to religion, education, art, science or charitable purposes, historical monuments or hospitals

pillaging

rape, sexual slavery, forced pregnancy or any other form of sexual violence

conscripting or enlisting children under the age of 15 years into armed forces or groups or using them to participate actively in hostilities.

What do international rules say about the bombing of hospitals?

International humanitarian law bans any attack on patients and medical personnel - indeed, any attack on medical facilities, which are zones that must be respected under the rules of war.

Even if combatants, such as the Taliban, take refuge in them, they should not be attacked.

In the case of Kunduz, US investigators say that the attacking plane fired 211 shells at the compound over a 25-minute period before commanders realised their mistake and ordered a halt.

Under rules established by the ICC, any such incident would probably result in too high a number of civilian casualties - what is called the rule of proportionality.

According to Human Rights Watch, external, "given the hospital's protected status and the large numbers of civilians and medical personnel in the facility, attacking the hospital would still likely have been an unlawfully disproportionate attack, causing greater harm to civilians and civilian structures than any immediate military gain.

"The laws of war require that even if military forces misuse a hospital to deploy able-bodied combatants or weapons, the attacking force must issue a warning to cease this misuse, setting a reasonable time limit for it to end, and attacking only after such a warning has gone unheeded," the group said in a statement.

Under international humanitarian law, external "constant care must be taken to spare the civilian population, civilians and civilian objects".

Medical units, the rules say, external, "must be respected and protected in all circumstances", although "they lose their protection if they are being used, outside their humanitarian function, to commit acts harmful to the enemy".

Have there been other such bombings elsewhere?

In February 2009, nine people were killed by shells which hit a hospital, external in a rebel-held area of north-east Sri Lanka.

The hospital, in the town of Puthukkudiyiruppu, Mullaitivu district, was hit three times in 24 hours, and shells were said to have hit a crowded paediatric unit.

Sri Lanka's army denied it was behind the shelling. It accused separatist Tamil Tiger rebels of using civilians as human shields.

The International Committee of the Red Cross at the time called the strikes "significant breaches of international humanitarian law".

A Palestinian employee inspects damages at the hospital in the Gaza Strip after an air strike last year

Last year, at least five people were killed and 70 injured by an Israeli strike on a hospital in Gaza.

Doctors at the al-Aqsa Hospital in Deir al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip say several Israeli tank shells hit the hospital's reception, intensive care unit and operating theatres.

The Israeli military said it had targeted a cache of anti-tank missiles in the hospital's "immediate vicinity".

"Civilian casualties are a tragic inevitability of [Hamas'] brutal and systematic exploitation of homes, hospitals and mosques in Gaza," it said in a statement.

Has something like this happened before in Afghanistan?

Experts point out that this is not the first time international humanitarian law may have been violated in Afghanistan's current conflict.

At least 18,000 civilians have died in 14 years of war. Hundreds of people have been killed in coalition raids and bombings - although many more have been killed in militant attacks.

At times, foreign and local troops have entered medical facilities to arrest people.

But because of its long-term implications on medical assistance, the Kunduz incident, in the words of one ICRC official, ranks as an especially serious one.