Subhas Chandra Bose: Looking for India's 'lost' leader

- Published

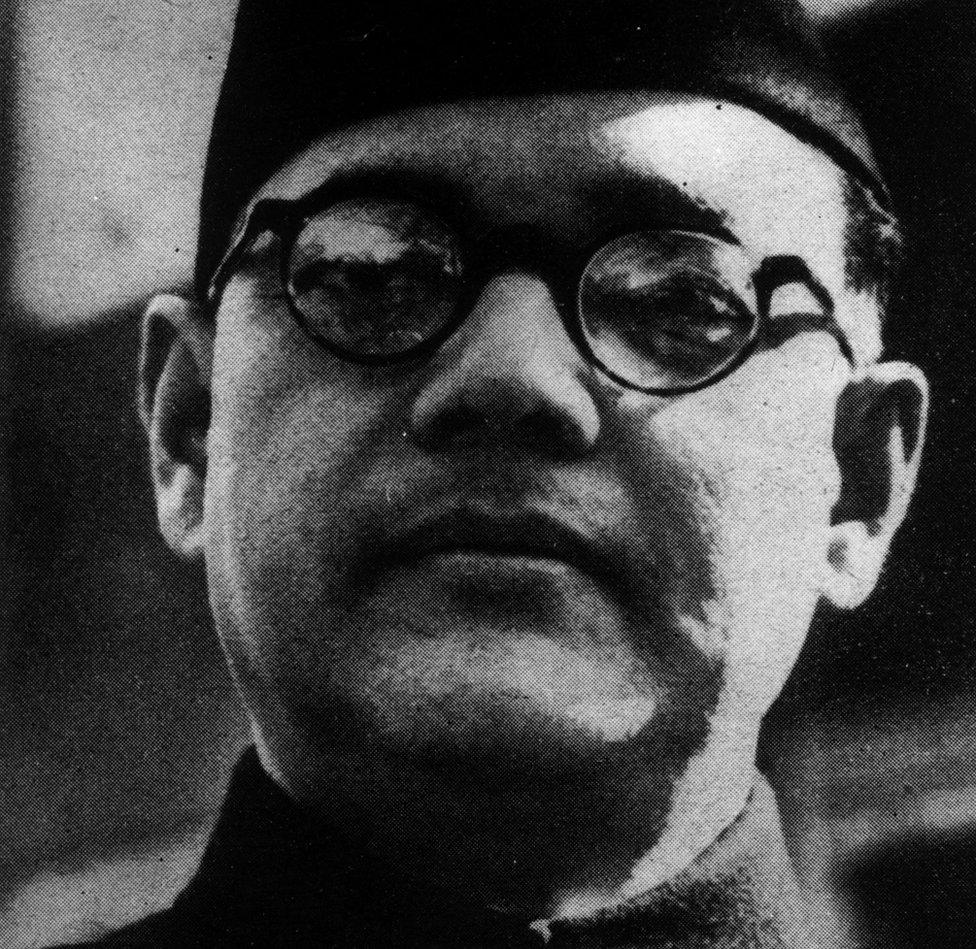

Subhas Chandra Bose became an important figure for nationalists

India's leaders need to tiptoe warily when honouring the country's pantheon of political heroes.

It's difficult to talk up one without being seen as talking down another - and when they are championed by different political, religious, regional and caste groups, you can see the problem.

Almost 70 years after independence, the fate of the nationalist firebrands of that era continues to excite powerful emotions.

That is true above all for the man often regarded as India's 'lost' leader, the charismatic Subhas Chandra Bose.

Prime minister Narendra Modi will need to bear that in mind this week when he hosts 50 or so relatives of Bose, who is also known by the title 'Netaji' or 'respected leader'.

He was a radical nationalist from an elite Bengali family who allied in the 1940s with Nazi Germany and imperial Japan to seek to evict Britain from India.

After Second World War adventures that included a dramatic escape from house arrest in India, a meeting with Hitler, an epic journey in a German submarine to Japanese-held Sumatra and the raising of an army of Indians in south-east Asia, Bose died in a plane crash in Taiwan on 18 August 1945. Or did he?

Official files released

The release last month of long-closed official files, external in Kolkata has rekindled speculation that Netaji survived the war and was either held prisoner by the Russians, lived on as a hermit-like holy man, or simply lived out his life in the style of the legendary King Arthur - standing by should his country need him as its saviour.

Historians, including those within his immediate family, are broadly convinced that Bose did indeed lose his life in that 1945 air accident.

But some family members, and many who see themselves as inheritors of his political legacy, believe fervently that Netaji did not die in Taiwan - and that somewhere in hidden archives lies buried the true story of their leader's fate.

Narendra Modi will meet relatives of Bose

Bose is a national figure, but Bengalis take particular pride in him and a party with seats in the West Bengal state assembly still fiercely champions his reputation.

Mamata Banerjee, the state's chief minister, may have imagined that declassifying files about him would be a good political move.

She went further, though, and suggested that the documents give credence, external to the notion that Bose survived the air crash.

"From whatever I have seen, it seems he was alive after 1945."

Not so, insists the distinguished historian Sugata Bose - Netaji's grand-nephew and his biographer.

He says the files "contain nothing substantially new" - though they demonstrate the intense surveillance of the Bose family and dutifully record all the speculation and stray rumour about Bose's fate.

Family issues

Family politics are often, of course, as contested as national politics - and Narenda Modi has that minefield to contend with too.

Subhas Chandra Bose was one of 14 siblings and the extended family is huge.

Subhas Chandra Bose:

Born: 23 January 1897

Twice-elected president of the Indian National Congress, founder and president of the All India Forward Bloc, and founder of the Provisional Government of Free India.

Advocated armed struggle for Indian independence from the British Empire.

Placed under house arrest by the British before escaping from India in 1940, arriving in Germany in 1941., external

Attempted to rid India of British rule during World War Two by enlisting the help of Nazi Germany and Japan.

Played a role in establishing a Free India Legion, made up of Indians captured by Rommel's Afrika Korps, formed to aid a possible future German land invasion of India.

Moved to Japanese-held Sumatra in 1943, where he revamped the Indian National Army, which fought alongside the Japanese army in its unsuccessful attempt to invade India.

Believed to have died in 1945 when his plane crashed in Taiwan.

There have been mutterings within the Bose clan that the prime minister is giving a platform to distant relatives who are "non-believers" - who refuse to accept the well-documented account of Bose's death and espouse what others within the family have described to me as "wild stories that are just so tiresome".

"It is odd that Narendra Modi, who keeps his own family at arm's length, should be so keen to be seen rubbing shoulders with certain members of Netaji's extended family," Sugata Bose tartly remarked in a recent article, external.

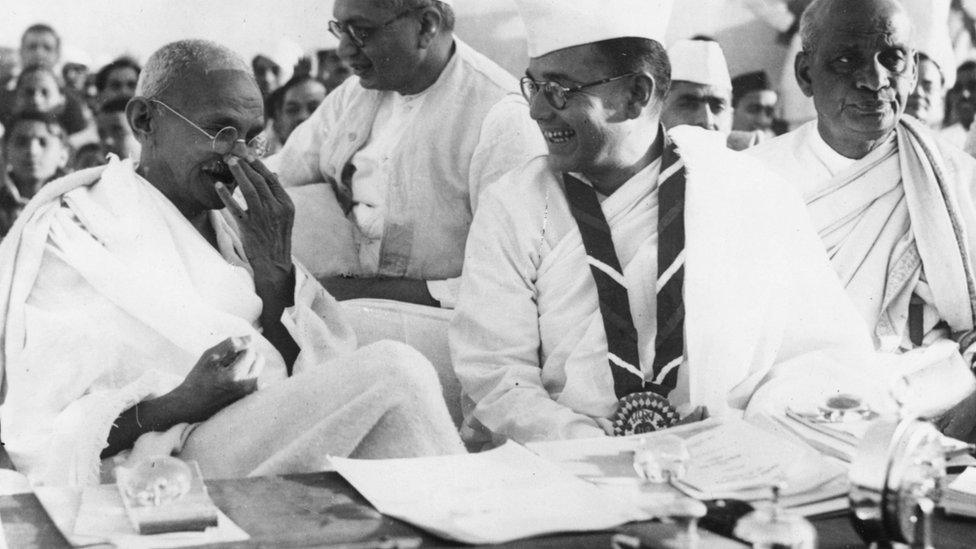

Many Indians refuse to believe that Bose (second from right) died in a plane crash

"I had heard he was opposed to family-based politics."

Absent from the gathering at the prime minister's official residence in Delhi will be Netaji's only child - a daughter he last saw when she was four weeks old. Anita Pfaff, a retired German academic - Bose's wife was Austrian - tells me she hasn't received a direct invitation from Modi's office.

While she understands she is welcome to attend, she hopes to meet the prime minister one-to-one in a few months' time.

The controversy surrounding Bose's fate marks him out from other independence-era leaders, but he's not the only one whose standing and legacy is contested.

Mahatma Gandhi of course is a renowned apostle of non-violence and advocate of religious harmony. But he's no longer so well regarded by those at the bottom of India's caste hierarchy whose interests he championed.

New icon

Among many, he has been displaced as icon by BR 'Babasaheb' Ambedkar, the jurist who wrote India's constitution and who was himself (unlike Gandhi) a dalit, from one of the marginalised groups once labelled as "untouchable".

As low caste parties have increased in strength, Ambedkar's image is much more on display and statues to him have proliferated.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the man who led India to independence, is commemorated in statues and street names - and his political legacy is kept alive in another, more partisan manner.

Ambedkar is sometimes described as the "darling of the dispossessed"

His daughter and grandson followed in his political footsteps as prime minister and his great-grandson, Rahul Gandhi, is the great hope of the opposition Congress party.

When you think of family politics in India, it's the Nehru-Gandhi political dynasty (nothing to do with Mahatma Gandhi in this case, by the way) that has dominated Congress for 80 years which first springs to mind.

A dynasty that attracts both deference and derision.

As for Subhas Chandra Bose, those family members meeting Mr Modi and those staying away all agree on one issue - that the Delhi government must open up its own remaining Netaji files.

Ms Pfaff says she expects these to offer "proof of continued co-operation of the Indian and British secret services post-independence and spying on members of my family and interception of letters".

That wouldn't put the Indian government in a very positive light - which, she suspects, may be why the archives have remained under lock and key for so long.

Over to you, prime minister.

Andrew Whitehead was the BBC India correspondent and is now honorary professor at the Institute of Asia and Pacific Studies, University of Nottingham

- Published18 September 2015

- Published2 October 2015