Creeping capitalism: How North Korea is changing

- Published

High heels and Western dress are evident among Pyongyang's commuters

What should we make of North Korea? It's the most isolated country on the planet with a leadership which boasts that it has nuclear devices. Our correspondent Steve Evans is there and reports that it is a country which is changing.

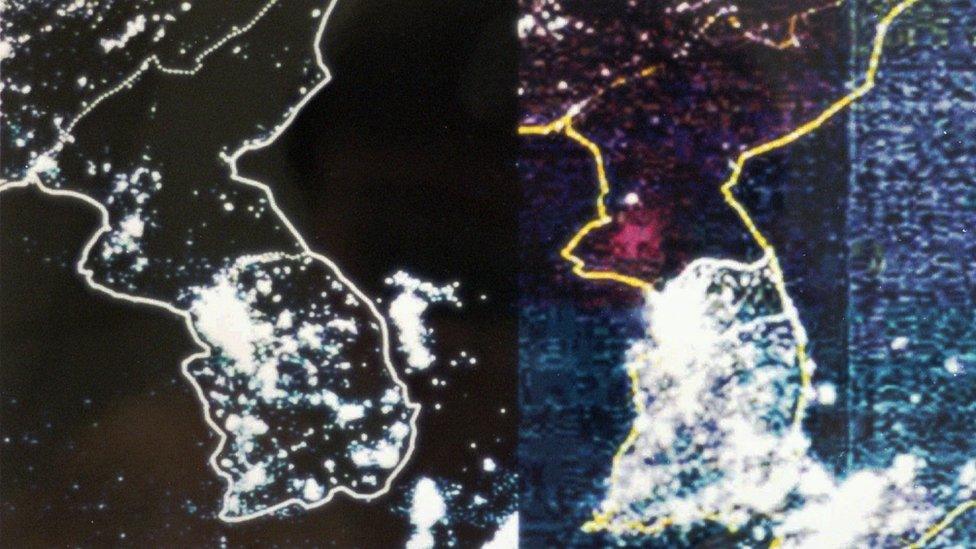

What jumps out at you as you drive into Pyongyang is the darkness. There is a famous picture of North Korea taken from a satellite showing the Democratic People's Republic of Korea as a dark mass in contrast to the neon festival of light which is South Korea shining up into space.

But that darkness becomes real at street level: as night falls, you pass apartment block after apartment block in Pyongyang with barely a light glimmering from the windows. This remains a country where electricity is in short supply.

Satellite photos taken in 1986 (L) and 1996 (R) of the Korean Peninsula at night show how brightness greatly expanded in South Korea, the lower part of the peninsula, while darkness spread throughout North Korea, except Pyongyang, during that decade

During the day, small solar panels are visible on some balconies, an indication of how ordinary people are bypassing official sources - literally taking power into their own hands.

That assertion of private action is happening in lots of ways. After the famine in the 90s, the economy started to change. Starving people found ways of growing their own food and then trading it - private markets helped relieve a problem of life and death. Once invented, these markets have refused to disappear. They are now tacitly acknowledged by the authorities. On top of that, some enterprises behave like capitalist organisations, offering managers the ability to keep profits - they get a private cut and the state gets its public cut.

'Creeping capitalism'

A kind of creeping capitalism is occurring in North Korea.

That means there is money there - some money for some people. As well as a changing way of doing business internally, a porous border with China to the north means all kinds of goods are entering. In the department stores of Pyongyang, products are available for those who can afford them (the crucial caveat).

North Korea is one of poorest countries in the region and among the most insular in the world

It should be said, though, that North Korea remains much poorer than many other countries, particularly South Korea. Even in Pyongyang, there are not riches to compare with Seoul.

Apart from the view of North Korea from space, there is another classic picture: that of long, empty roads, completely devoid of traffic apart from the odd ox cart.

Today, there are traffic jams in Pyongyang, traffic jams on roads clogged with Chinese vehicles, but also with BMWs and VWs.

Political control

But what hasn't changed is the level of political control. On Saturday, there is a big parade for what is a big celebration. Dignitaries and busloads of journalists are arriving to witness a display of military hardware - and of power over the country's own citizenry. Every street seems to have gangs of workers, often in military uniform. The squares of Pyongyang are filled with young people rehearsing the most minute choreographed move.

Minders are allocated to all journalists and these government officials supervise their charges rigorously, ruling out any contact with ordinary people, telling cameramen not to film. Books about North Korea are confiscated from incomers at the spanking new Pyongyang Airport.

Pyongyang has a new international airport

The airport illustrates the dilemma for the regime. It's been built to facilitate the arrival of millions of visitors clutching dollars and euros.

But the authorities remain very mistrustful of outsiders. They want them and their cash but not their disrupting ideas. How can North Korea get outsiders in while blocking material which it feels would corrupt the citizens with dangerous outside ideas like democracy or Christianity?

- Published26 April 2019

- Published19 July 2023