Kashmir territories - full profile

- Published

The former princely state of Kashmir has been partitioned between India and Pakistan since 1947, to the satisfaction of neither country nor the Kashmiris themselves.

Failure to agree on the status of the territory by diplomatic means has brought India and Pakistan to war on a number of occasions, and ignited an insurgency that continued unabated for decades.

Partition

When India and Pakistan gained independence from British rule in 1947, the various princely rulers were able to choose which state to join.

The Maharaja of Kashmir, Hari Singh, was the Hindu head of a majority Muslim state sandwiched between the two countries, and could not decide. He signed an interim "standstill" agreement to maintain transport and other services with Pakistan.

Islam is the dominant religion in the Kashmir Valley

In October 1947 tribesmen from Pakistan invaded Kashmir, spurred by reports of attacks on Muslims and frustrated by Hari Singh's delaying tactics.The Maharaja asked for Indian military assistance.

India's governor-general, Lord Mountbatten, believed peace would best be served by Kashmir's joining India on a temporary basis, pending a vote on its ultimate status. Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession that month, ceding control over foreign and defence policy to India.

Indian troops took two-thirds of the territory, and Pakistan seized the northern remainder. China occupied eastern parts of the state in the 1950s.

Dispute

Whether the Instrument of Accession or the entry of Indian troops came first remains a major source of dispute between India and Pakistan. India insists that Hari Singh signed first, thereby legitimising the presence of their troops. Pakistan is adamant that the Maharaja could not have signed before the troops arrived, and that he and India had therefore ignored the "standstill" agreement with Pakistan.

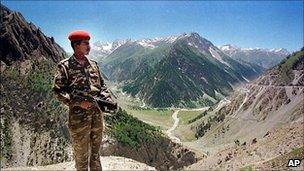

The mountains of Kashmir, scene of a violent territorial dispute

Pakistan demands a referendum to decide the status of Kashmir, while Delhi argues that, by voting in successive Indian state and national elections, Kashmiris have confirmed their accesson to India. Pakistan cites numerous UN resolutions in favour of a UN-run referendum, while India says the Simla Agreement of 1972 binds the two countries to solve the problem on a state-to-state basis.

There has been no significant movement from these positions in decades. In addition, some Kashmiris seek a third option - independence - which neither India nor Pakistan is prepared to contemplate.

Line of Control

The two countries fought wars over Kashmir in 1947-48 and 1965. They formalised the original ceasefire line as the Line of Control in the Simla Agreement, but this did not prevent further clashes in 1999 on the Siachen Glacier, which is beyond the Line of Control. India and Pakistan came close to war again in 2002.

The situation was further complicated by an Islamist-led insurgency that broke out in 1989. India gave the army additional authority to end the insurgency under the controversial Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). Despite occasional reviews of the AFSPA, it still remains in force in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir.

In the summer of 2010, 20 years after the AFSPA was imposed in Jammu and Kashmir, pro-Pakistan and pro-independence public protests erupted, and clashes with Indian security forces left more than 100 people dead.

Given that India and Pakistan both have nuclear weapons, the stakes in the dispute are high.

A thaw in relations after 2002, which saw some road and rail communications into Pakistan reopened, ended abruptly with the 2008 terror attacks in Mumbai. India blamed Pakistani and Kashmiri Islamists, in particular the Lashkar-e-Toiba group, for the attacks.

Talks between the two countries on improving ties across the Kashmiri Line of Control resumed in 2010, and relations slowly started to improve again.

By 2012, with India promising an amnesty to those who took part in the violent protests of 2010 and Pakistan gradually withdrawing financial support from insurgents fighting Indian rule in the Kashmir Valley, many former militants had become convinced of the futility of the armed struggle against the Indian authorities.But official figures show a steady increase in young men joining armed groups from 2014, with the local Hizbul Mujahideen outfit making a comeback. Kashmir analysts attribute this to anger over the hanging in 2013 of Indian Parliament terror attacker Afzal Guru, and disillusion with the governing People's Democratic Party.

Division

The population of historic Kashmir is divided into about 10 million people in Indian-administrated Jammu and Kashmir and 4.5 million in Pakistani-run Azad Kashmir. There are a further 1.8 million people in the Gilgit-Baltistan autonomous territory, which Pakistan created from northern Kashmir and the two small princely states of Hunza and Nagar in 1970.

Kashmir is renowned as a source for the fine wool known as cashmere

The government of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir has often been led by the National Conference, a pro-Indian party led by the Abdullah political dynasty. Pakistan runs Azad Jammu and Kashmir as a self-governing state, in which the Muslim Conference has played a prominent role for decades.

The National Conference moved from an almost pro-independence stance in the 1950s to accepting the status of a union state within India, albeit with more autonomy than other states.

Jammu and Kashmir is diverse in religion and culture. It consists of the heavily-populated and overwhelmingly Muslim Kashmir Valley, the mainly Hindu Jammu district, and Ladakh, which has a roughly even number of Buddhists and Shia Muslims.

The Hindus of Jammu and the Ladakhis back India in the dispute, although there is a campaign in the Leh District of Ladakh to be upgraded into a separate union territory in order to reflect its predominantly Buddhist identity. India gave the two districts of Ladakh some additional autonomy within Jammu and Kashmir in 1995.

Kashmir's economy is predominantly agrarian. The important tourism sector in Indian-administered Kashmir was hard hit by the post-1989 insurgency, but has recently bounced back and in 2011 a record 1.1m tourists visited, mainly from India itself.

Dal Lake in Srinagar was at one time popular with tourists