Paris attacks: Fighting Islamic State at home and abroad

- Published

At least one of the perpetrators of Friday's attack was known to French authorities

French President Francois Hollande has spoken of waging "a pitiless war" against those responsible for the latest horrors in Paris. The rhetoric is strong. Security has been stepped up. Troops have been drafted in.

But the weekend's bomb attacks and shootings have highlighted once again the difficulties in providing total security in a modern, open Western capital.

But to what extent was there a lapse in security? Might or even should the French intelligence services have stopped this attack?

And what about the broader campaign against the so-called Islamic State (IS) abroad? Is anything likely to change there in the wake of the murderous carnage on the streets of the French capital?

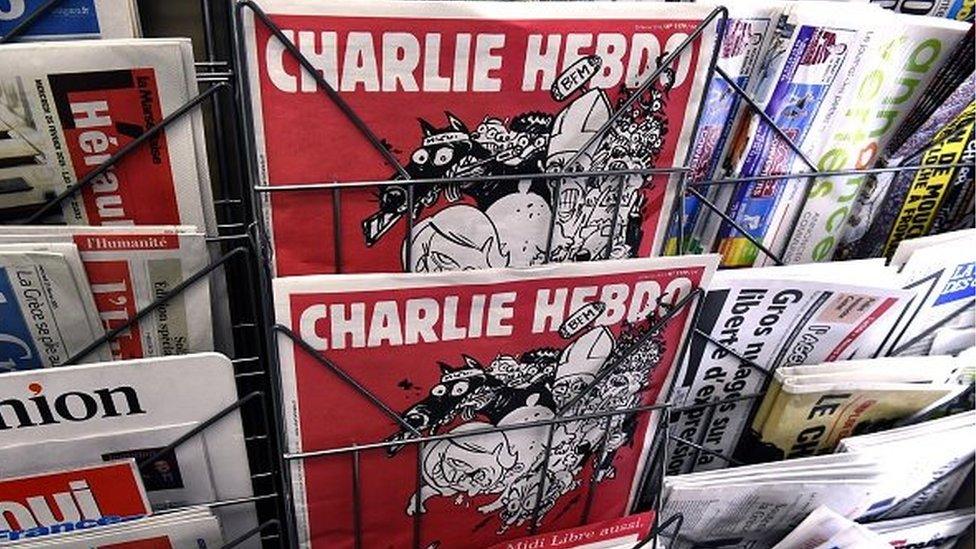

The events of last January - the attacks on the offices of the satirical paper Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket - were bad in themselves, but they represented a terrible warning that worse was to come.

A month after the massacre of the Charlie Hebdo editorial staff, the weekly paper went back on newsstands

In the wake of those attacks, the security services were reinforced.

Hundreds of new posts were created at the various French intelligence agencies, and new arrangements were established to enhance co-ordination and information sharing between them.

Inevitably, this all requires time to take effect and many of those new posts are only coming on stream now. But even these reinforcements may be insufficient for the job at hand.

Once again - just as in January - it looks as though at least one of the perpetrators of last Friday's attacks was known to the French intelligence services.

The Bataclan theatre was one of the sites that was struck, by a man known to police

Ismail Omar Mostefai - one of the suicide bombers at the Bataclan concert hall - was a French citizen and petty criminal.

He had been on the radar of the intelligence services since 2010 as being at risk of radicalisation. According to the Le Monde newspaper, he may have spent time in Syria between 2013 and 2014.

For whatever reason, alarm bells did not ring if and when he returned. French security sources have in the past complained at being simply inundated with case files.

There are just too many potential targets to watch and if individuals appear uninvolved in any suspicious activities, it is very hard to justify the deployment of scarce surveillance resources against them.

Links to Belgium

Mostefai's biography is typical of this generation of radicalised activists.

What seems to be different about these latest attacks though - and here the French authorities have given few details - is that they clearly believe that there is an external guiding hand behind the operation.

The cell that carried out the Paris attacks seems to have links into Belgium, another long-time focus of Islamist extremism.

US-led airstrikes have been used to try and contain IS

So while much has been made of the differences between al-Qaeda and IS - not least the latter's determination to secure and hold a territorial base in the Middle East, IS too is now demonstrating its long reach abroad.

The downing of the Russian airliner over Egypt, bombings in Turkey and against Hezbollah in Lebanon, and now these attacks in Paris all demonstrate its ability to strike against its enemies far from its heartland in Syria and Iraq.

So quite apart from stepped-up and streamlined domestic and Europe-wide counter-terrorism efforts, the terrible events in Paris suggest the need for a new look at how IS can be defeated. And here too there are few easy answers.

Syria power vacuum

Up to now, the focus has been largely on containing IS in those areas of Iraq and Syria that it controls. This has been the job of US and allied air power, with the constant refrain that without effective ground forces, it will be very difficult to roll back IS entirely.

More recently, things have begun to change. Kurdish forces have had significant local success retaking the town of Sinjar. Some progress has been made by Iraqi forces around Ramadi.

Kurdish fighters have driven IS out of Sinjar in Iraq

There are more US and other foreign advisers with the anti-IS ground forces, and more US aircraft have been deployed to bases in Turkey from where they can spend much more time over Syria.

There are even the first glimmers of the emergence of a new international peace plan for Syria, though crucially this has been drafted without the direct involvement of any of the warring factions on the ground.

Bringing an end to the power vacuum in much of Syria is a crucial condition for defeating IS. But it is hard to see this phenomenon disappearing altogether.

IS itself is simply a new eruption of the radicalism of al-Qaeda fighters who were forced underground in Iraq during the "Sunni Awakening".

The removal of its territorial base and the constant harrying of its leaders did though contain and deplete al-Qaeda.

Grimly though, there may be no permanent answer to this kind of challenge.

Security services need to be at the top of their game. European societies need to be better integrated. Countries in the Middle East need to be better able to serve the needs of all their citizens.

That's just three ambitious wishes for the New Year, you may say, after 12 months which, in Paris, is ending even more horribly than it began.