AirAsia probe: Anatomy of an avoidable crash

- Published

Indonesian transportation safety committee chief Soerjanto Tjahjono holds an aircraft model as he explains the report to journalists

Some faulty soldering was the trigger for the clearly avoidable crash of the AirAsia plane in the Java Sea in December 2014, a report from Indonesia's National Transport Safety Committee says.

It meant that a computer alarm kept going off, and in their attempt to fix the issue mid-flight, the crew lost control of the aircraft. All 162 people on board the Airbus A320 died.

The report suggests that the experienced pilot pulled a circuit breaker because he may have seen engineers do a similar thing to resolve the same problem on the ground. It is like pulling the plug to reset your computer.

Pilots are allowed to do it but only in extreme circumstances, and only when they fully understand the impact it will have.

This time around the impact seemed to take the crew by surprise. Pulling the circuit breaker switched off the autopilot.

With no autopilot, the less experienced co-pilot took over the plane. That in itself should not be a problem. But without the computer to help, aircraft can fly a little differently. It goes into a state called "alternate law".

Delayed response

One experienced pilot told me that the controls can become much more sensitive and take a few minutes to get used to.

The report says the co-pilot seemed to become disorientated as the aircraft banked sharply. He kept pulling the nose up until the plane stalled. That is not like an engine stalling on a car, but when there is not enough air going over the wings to create the lift that keeps the aircraft in the sky.

Investigators use words like "delayed response", "startled" and "disorientated" saying of the co-pilot: "He did not react appropriately in this complex emergency."

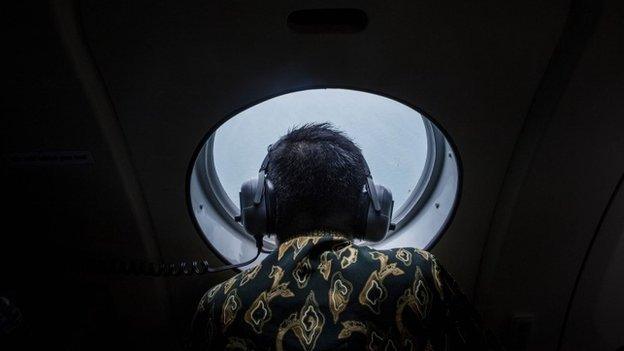

The wreckage of the plane was located days after the crash

It seems the more experienced pilot did not take control, as he is trained to do. He was doing the opposite of the co-pilot, pushing the nose down to come out of the stall, but the report says it did not have any effect because the aircraft averages out what the two control sticks are doing.

On an Airbus it is hard to see what your colleague is up to. The sticks are like computer joysticks and they sit on each side of the cockpit, on the armrest, rather than between the feet.

Meanwhile, we have found out that the same part that triggered the computer alarm had been faulty 23 times in the year building up to the crash. And four times during the final flight itself.

Precedent

Not for the first time, the spotlight falls on the way aircraft are maintained and the way crews are trained.

Despite early assumptions that this was down to storms, it seems the weather had nothing to do with it.

It all mirrors an accident in 2009, when an Air France Airbus crashed over the Atlantic killing 228 people.

Again, the trigger was a relatively simple mechanical problem. A thin tube iced up, which meant the aircraft could not tell how fast it was going.

The autopilot disengaged, alarms kept going off and a confused crew then failed to control their serviceable plane, which stalled at high altitude.

Back then it led to calls for better pilot training, especially with high altitude emergencies.

- Published1 December 2015

- Published1 December 2015

- Published5 January 2015