The amazing adventures of Sue in Tibet and her creator

- Published

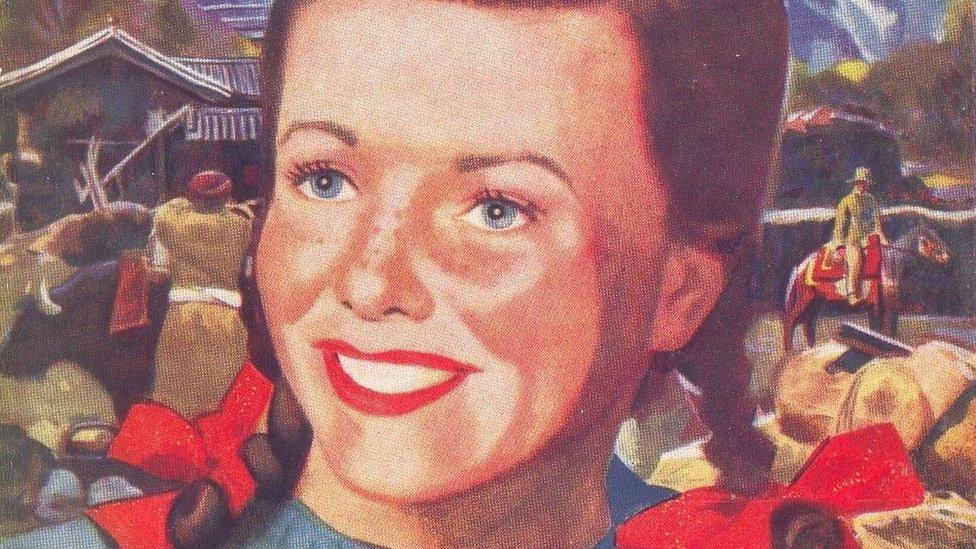

The cover art for Sue in Tibet shows a smiling girl, poised for adventure

Girls did not often star in the adventure stories of the early 20th Century, but the chance discovery of a little-known book by the daughter of an American missionary who lived in a Tibetan border town led researcher Tricia Kehoe to uncover an extraordinary life story, one marred by tragedy.

Everybody remembers when Tintin went to Tibet, but not what happened when Sue was there.

While browsing around a tiny second-hand bookshop in Nottingham, I came across a dusty, worn cloth-covered out-of-print book entitled "Sue in Tibet". As a scholar of Tibetan studies, I was familiar with Tibet-based adventure and mystery novels published in the 1920s, but these were invariably centred on the stories of the men.

This was intriguing because it looked like it could be the first piece of western children's literature ever set in Tibet, and its main character was a teenage girl. Published in 1942, it tells the story of Sue Shelby, the eldest daughter of an American missionary family stationed in the remote Tibetan border town of Batang.

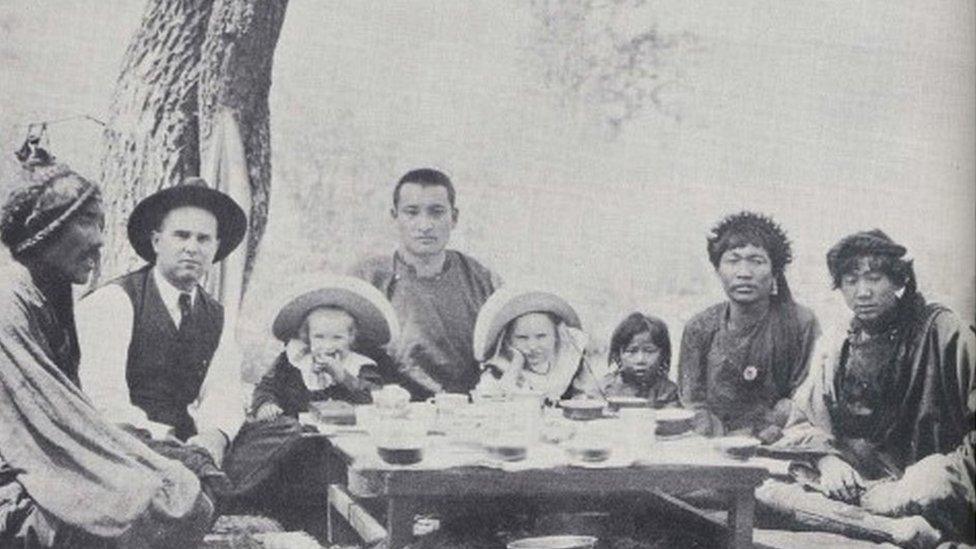

This photograph may record the Shelton family's first journey from the interior of China into Tibet

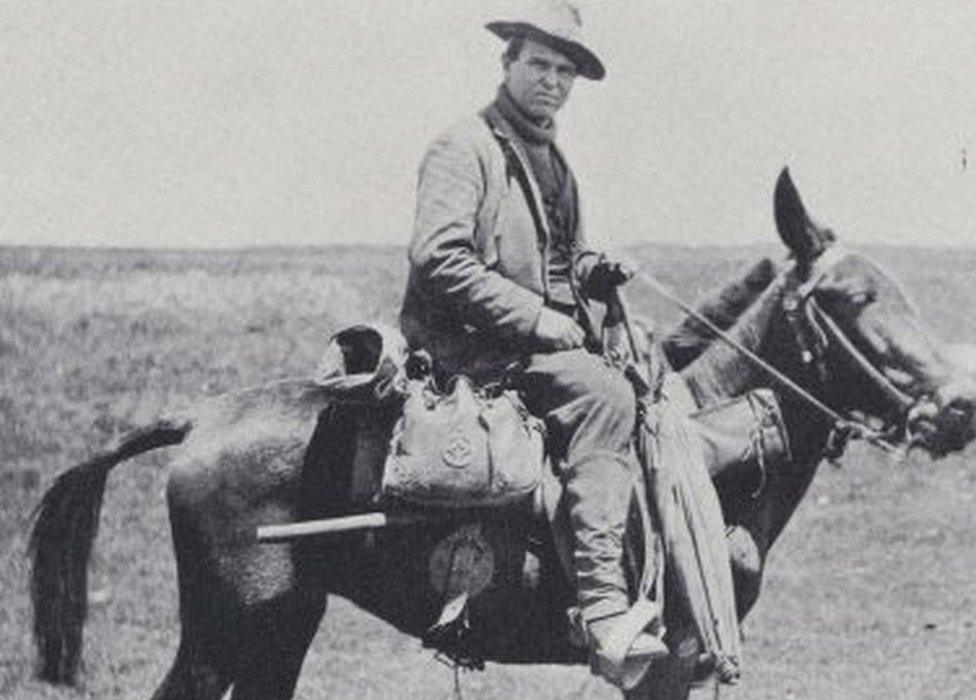

Set against the backdrop of rampant banditry and skirmishes between Tibetan and Chinese soldiers, it begins with the dangerous journey on horseback across snow-capped mountains by Sue's family before they eventually settle in Batang. By the end Sue, fluent in Chinese and Tibetan, acts as an interpreter at a crucial military conference, so ensuring peace at a time of unrest.

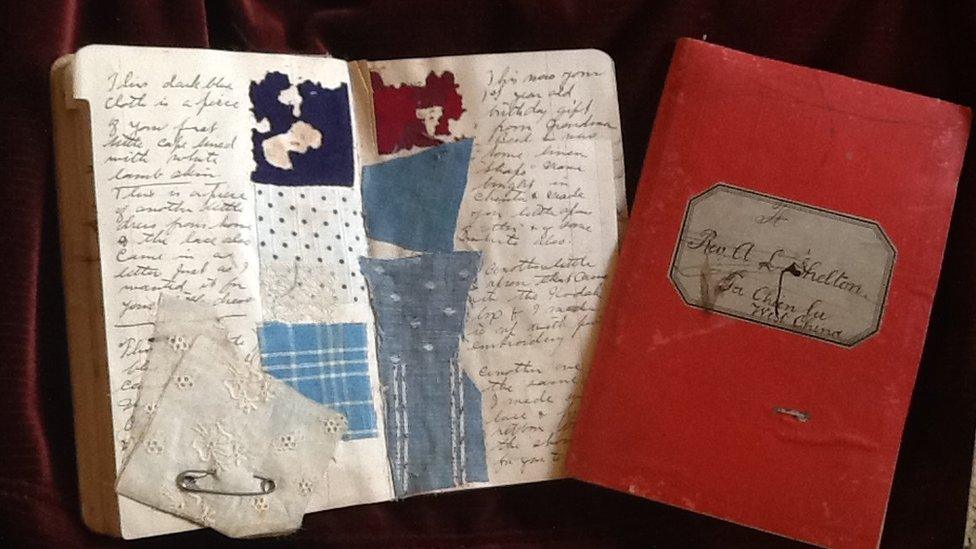

Its observations are astonishingly accurate - because it is based very closely on the true-life adventures of its author, Dorris Shelton Still. However, her story did not have the same happy ending. As a woman back in the United States, so her children told me, Dorris almost never spoke of her unique childhood.

The Shelton family making a precarious crossing over a lake in the Batang region

Like Sue, Dorris was the eldest daughter of the Sheltons, an American missionary family stationed in the remote Sino-Tibetan border town of Batang between 1908 and 1921. Batang was not a strange or exotic land for Dorris, it was home. Clues to the Sheltons' life come from Sue's story too.

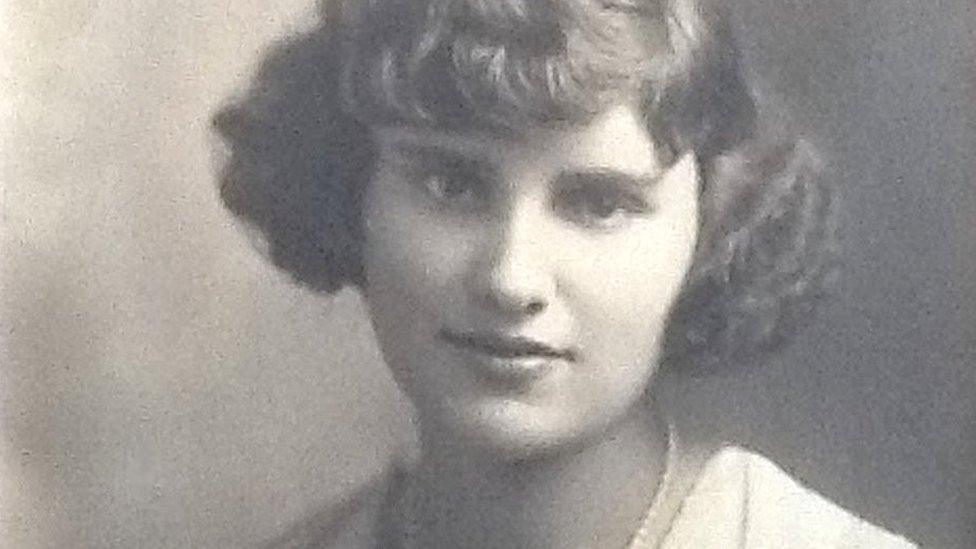

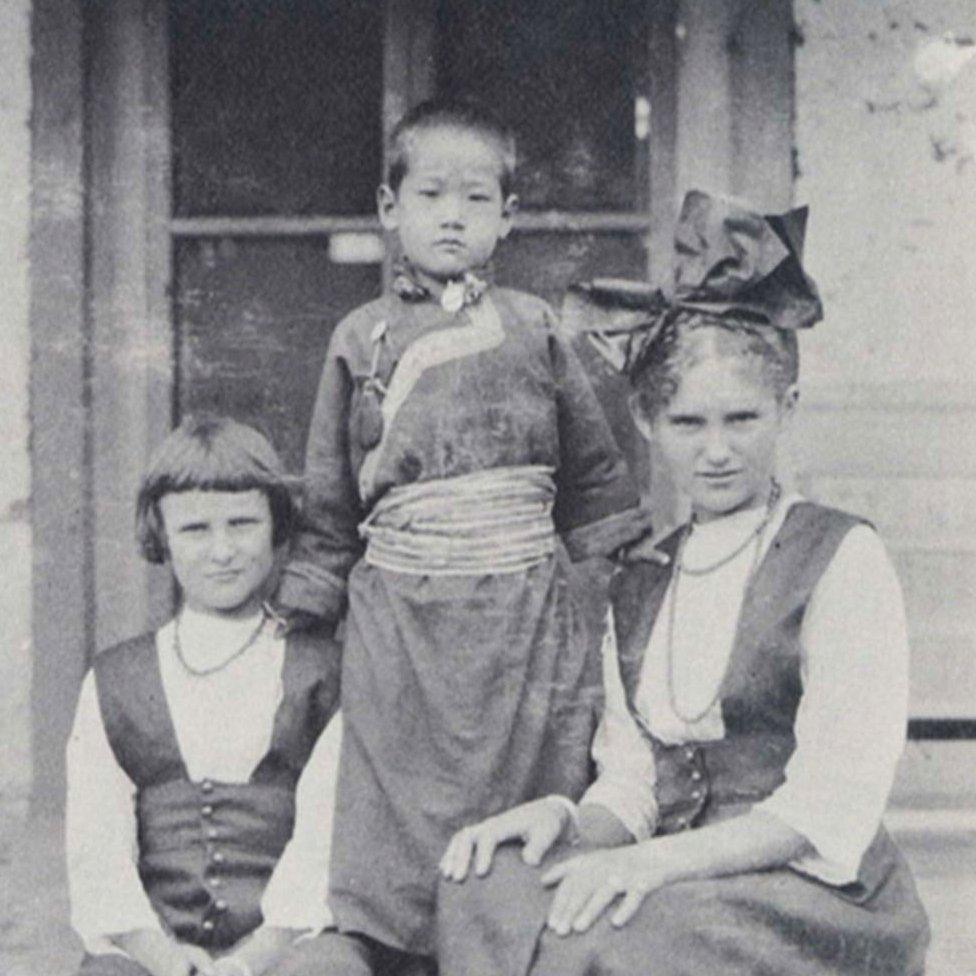

Dorris Shelton was sent away from Batang in 1921 to attend boarding school in the US

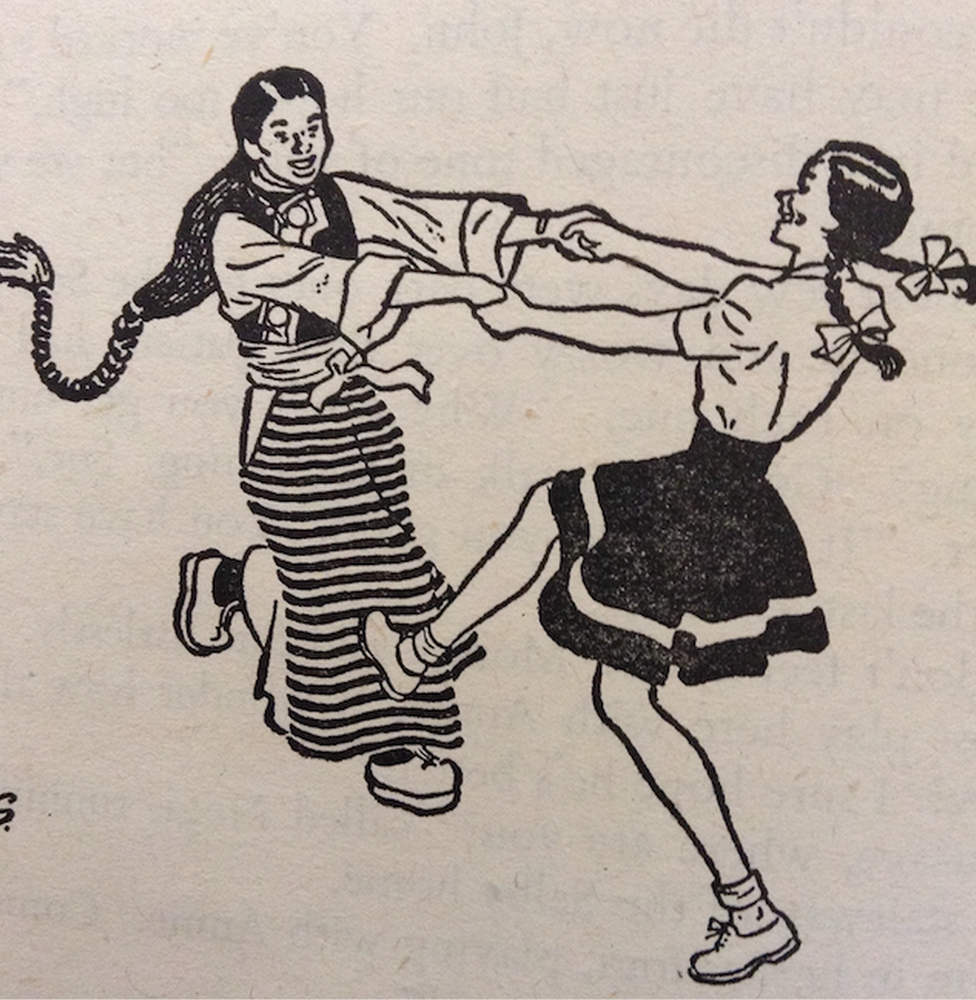

Sue in Tibet recounts the heroine's close friendships with Tibetan girls in Batang

Just a few years after the British invasion of Lhasa in 1905 and a subsequent massacre of missionaries and converts by Tibetan lamas in Batang itself, the fictional family are received with a mixture of curiosity, fear and suspicion. Nevertheless, Sue becomes best friends with local girl Nogi, who teaches her to apply yak butter to her skin after bathing. They swap snacks of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for yak meat and dried yak cheese.

Sue even befriends a so-called Living Buddha, known in Tibet as a tulku or reincarnated lama. This story has some basis in reality as one remarkable photograph now held at the Newark Museum shows. It documents the occasion when the Shelton family sat down to a picnic with an incarnate lama who had been disbarred from priestly functions because he fell in love.

When Sue met a so-called Living Buddha

When Dorris met an incarnate lama (second from right)

As she notes in her memoirs, Dorris never forgot her friends in Batang, and would regularly pine for butter tea and tsampa, the traditional staples of Tibet. Although she longed to return, it was never to be.

But the triumphant climax of Sue in Tibet is where fiction departs from reality. When Sue's father is prevented by injury from acting as interpreter at a crucial military conference, Sue jumps in, and after a gruelling journey on horseback, she saves the day, returning to a heroine's welcome in Batang.

It was not like that for Dorris and her sister, who were dressed like sober American girls and kept to a strict schooling schedule. In 1921, they were sent off to boarding school.

They were never again to see their father, the heroic doctor whom Sue's father is closely based on.

Dorris and her sister, despite their very Tibetan way of life, were kept in Western clothes while in Batang

While on a mission to Lhasa to set up a medical centre, he was shot by bandits on the road. He died days later. His family were not there, but a travelling companion later provided a graphic and tragic account of what happened, paying tribute to the doctor's courage and crediting him with saving his life. After the bandits moved on, they found the doctor lying on the side of the road.

"There were blood stains all over his face. I could see a large wound open on his forehead. "

He was desperate for water, but that was scarce. Nursed for a few days, the doctor knew what was coming once his arm was amputated.

"Ming Shang. I will be gone in a few days, no hope to live, I love you, be a good boy. I have told the other folk to look after you," Dr Shelton said.

"I was extremely sad, a man who loved me as his own son, now I had to carry his amputated arm on the back of my horse," the account goes on to say.

Her father, a doctor, was on the way to set up a medical mission in Lhasa, when he was killed by bandits

Even though Dorris went on to write about Sue in Tibet, her children believe the pain of the loss of her father lay behind her personal silence in her later years. Her granddaughter, Andrea Still does recall one conversation, possibly a tribute to Dorris's father's work as a doctor.

"She spoke about ...where Western and Eastern philosophies met with most friction. It was that if someone was injured...in Tibetan culture, they would write a prayer down on a slip of paper, cover the paper in mud and swallow it down while saying prayers and walking in supplication, while the Westerner finds his trusty doctor."

Dorris Shelton went on to involve herself in Tibetan causes from the US

Tibet clearly stayed with Dorris. She was involved in raising money to help Tibetan refugees and sponsoring Tibetan businesses in Dharamsala, the Indian city which has become a hub for Tibetan exiles. She also had private audiences with the Dalai Lama.

In many ways, the book was ahead of its time. In the 1940s, out of the 284 children's books published in the US, only 21 had girls as their main characters. Sue, however, is centre-stage. Faced with unfamiliar and dangerous situations, she is an independent and quick-thinking girl with a strong sense of curiosity and a passion for adventure.

It is clearly a reflection of Dorris's spirit too and she wrote about her time in Tibet with a poignant nostalgia in her later journals.

"We were happy youngsters in a beautiful land with friends we loved and endless wonderful things to do."