Afghanistan Taliban: Mistrust and fear in battle for Helmand

- Published

Afghan security forces try to douse a fire after a suicide car bomb blast attacked a military convoy in Lashkar Gah

For many in Lashkar Gah the question is whether to stay or go.

The battle for control of Afghanistan's Helmand province, the Taliban's traditional power base, has lasted for months. Lashkar Gah is the capital and in government hands.

But large swathes of the province's countryside, a centre for the drug trade that fuels the conflict, are controlled by the insurgents.

Many of my friends who still live in Lashkar Gah are thinking of getting out while they can.

Gone are the days when we enjoyed sitting on the banks of the Helmand river, watching sunsets, eating fresh fruit and chatting.

Then the gossip would be about a new car or a holiday abroad. Now it's about escaping.

The word on the street is that the Taliban are coming. But leaving the city is not an easy choice: my friends have families now, they have built houses and businesses.

Lashkar Gah is as busy as ever, but under the surface there's an edginess that's hard to miss

Ismat, a resident of embattled Sangin district on his way back home after being treated in Lashkar Gah for injuries sustained in crossfire

On edge

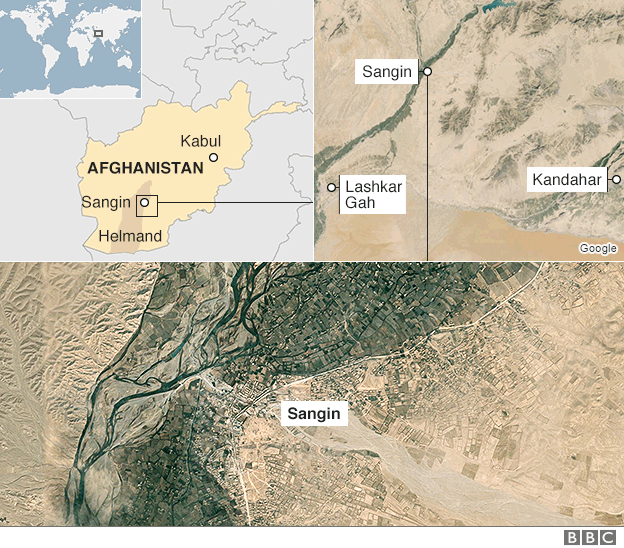

The situation in Sangin, less than 100 kilometres (62.5 miles) away, has put nerves on edge.

The town where British troops lost dozens of soldiers during their eight-year presence in the province more or less fell to the Taliban at the turn of the year with just a few members of the security forces still holding out.

But Helmand as a whole seems in danger of collapsing.

Not because the Taliban have become stronger but because the Afghan government appears to have become weaker here.

Critics say that the authorities suffer from poor leadership, corruption and a lack of communication. And all that has made the Taliban stronger.

One Taliban commander told the BBC that most of their weapons were sold to them by members of the Afghan security forces. It's a claim impossible to verify but insurgents have been observed using official army issue weaponry.

Helmand governor Mirza Khan Rahimi says the Taliban will be beaten back

The Helmand Governor, Mirza Khan Rahimi, is a heavily built veteran of the Afghan intelligence services.

Speaking to me in an interview, he brushed off accusations that he'd been ineffective in containing the insurgency:

"Withdrawal is a military tactic and we will soon clear those areas from the enemy," he said, referring to gains made by the Taliban in the province.

But questions over how well Helmand officials communicate and co-ordinate were raised when the governor's own deputy published an open letter to the president on Facebook, saying that if Helmand didn't get serious attention, it would fall into Taliban hands.

The deputy has since been referred to the prosecutor's office.

Chaos and confusion

Helmand police chief Abul Rahman Sarjang has also come under fire.

Sarjang literally means "the lead warrior" and in his first public speech the police chief appeared keen to live up to his name:

"I have not come here to make peace with the Taliban, I have come here to wage war," he said.

Locals are still mocking him for that speech. His first mission was to Marjah district where he was pushed back by the Taliban.

The area is now once again the focus of fresh fighting.

Adding to the confusion are some members of the provincial council, the elected local body made up of local elders and power brokers.

Most media outlets contact them for their opinion as representatives of the people but with everyone having their own interests and loyalties they are hardly impartial in their judgements.

And with so many officials apparently pulling in different directions, making claims and laying blame, observers say there is a danger of them becoming part of the problem. Helmand, they say, could become a second Kunduz, the northern provincial capital briefly taken by the Taliban late last year.

But Governor Rahimi says that won't happen.

"Helmand is not Kunduz," he told me. "We have enough forces - even though some say that the force is lacking a plan and co-ordination, but it's not like that. Helmand will hold its place, and not only that, we will make progress."

Kandahar vegetable market is busy but some residents are thinking about leaving

Officers conduct a search at a police post just 8km from the nearest Taliban checkpoint outside Kandahar

No relief

But the situation remains precarious, especially in Sangin where Afghan security forces are still cut off from an army brigade which is based just a couple of kilometres away.

A wounded local police commander told me about the situation he had witnessed there at the turn of the year:

"Our men were wounded, but we didn't have enough medical kit - some of them bled to death before our own eyes." he said. "Would our leaders abandon them like this, if these were their own sons?"

The operation to regain full control of Sangin is yet to get fully under way. But observers have little confidence in its success, pointing to a big operation in Helmand last spring codenamed "Zulfiqar".

Drivers at the Lashkar Gah bus terminal where taxis were heading off to Sangin when I visited told the BBC that Operation Zulfiqar had upset the local population.

"Afghan forces destroyed around 3,000 houses and nothing else," one told me, "They just made many more enemies."

Trust in the authorities has eroded to such an extent that some victims of the conflict shy away from getting medical treatment

Forgotten legacy

A lack of trust in the authorities is also apparent at Lashkar Gah's emergency medical centre.

Here I came on rumours - strongly denied - that the clinic was amputating soldiers' limbs that could be saved and treated elsewhere.

The day we interviewed two policemen from Sangin, eight injured men who had been shot in the arms and legs, had run away from Camp Bastion soon after landing there after their evacuation from Sangin.

One officer told us: "Over there the Taliban are chopping our heads off. Here the emergency clinic is chopping our limbs."

Amidst all the rumour, mistrust and confusion the Taliban are taking advantage.

They are promising good treatment for anyone who surrenders. They amnesty the person and pay a price for whatever the police officer may bring with him to the Taliban - be it an AK47 or a Humvee.

The Taliban also boast of having 600 "sleeping recruits" in Lashkar Gah, who they claim will rise inside the city once the insurgents attack.

This may be rhetoric but the fact that a Taliban flag is flying on the other side of the river, just eight kilometres to the north-west of the city centre, has frayed nerves.

Observers say that government officials insisting that all is well has led to a loss of faith in security and governance on the part of the residents of Lashkar Gah.

But Helmand police chief Abul Rahman Sarjang remains bullish, saying checkpoints are well guarded and vehicles and tanks are in place: "I give these people my word that if the Taliban enter in a thousand years, I will let the locals cut my throat as a punishment."