North Korea nuclear: What now after H-bomb test claim?

- Published

North Korea says it has carried out its first test of a hydrogen bomb with "perfect success". John Nilsson-Wright, head of the Asia Programme at Chatham House, examines how plausible the claim is, and what it could mean for the region.

What are North Korea's motives?

The North Korean leadership is trying to do two things:

Firstly, to strengthen Kim Jong-un's authority by demonstrating that the North is moving forward in its goal to enhance the country's military capabilities and specifically its nuclear deterrent.

Since the 1960s, successive leaders of the DPRK have sought to develop an effective nuclear weapons programme as a means of underlining the country's political and strategic autonomy, while also boosting the reputation of its individual leaders. Kim Jong un, since coming to power in December 2011, has made the goal of a strong economy and military the centrepiece of national policy.

The test comes a few days in advance of Kim's birthday and this demonstration of military defiance may be intended to bolster Kim's credentials as the country's supreme leader and effective commander-in-chief.

Secondly, by provoking international attention - by bringing the diplomatic spotlight back onto North Korea - the aim is to force the international community, and specifically the United States, to negotiate with the North.

Pyongyang hopes to prompt talks leading, amongst other things, to a peace treaty formally ending the Korean War, diplomatic recognition from the United States, and some measure of integration with the global economy and the relaxation of economic sanctions.

Was the latest nuclear test successful?

It's too early to say whether this was in fact a genuine H-bomb test. Early reports of the seismic activity surrounding the putative test site in the country's north-east suggest that it was a 6 kiloton test, roughly equivalent to the last test the North carried out in February 2013.

A genuine H-bomb would most likely produce a much higher yield and therefore technical specialists are sceptical about the North's claim to have tested a fully-fledged hydrogen bomb.

Some have speculated that hydrogen isotopes may have been used in the nuclear chain reaction, providing limited, formal confirmation of the "hydrogen" character of the bomb, but this would be far short of a genuine, fusion (as opposed to fission) device.

The Punggye-ri site has previously been used to conduct underground nuclear tests

It will take considerable time to gather sufficient technical data to ascertain the precise nature of the test.

Judging from the process of remote data gathering following the 2013 test, it will take weeks, perhaps months, for international scientists and monitoring agencies to be able to develop a clear view on the test.

What are the likely repercussions in the region?

The response from South Korea and Japan has been, as one would expect, sharply to condemn the actions of the North.

Together with their US ally, Seoul and Tokyo have anticipated the likelihood of a fourth North Korean test for some time and should already have devised a well-planned and co-ordinated response.

China has also spoken out forcefully against the actions of its North Korean ally and China's leader, Xi Jinping, will likely be intensely irritated by the further ratcheting up of tensions on the peninsula.

Senior Chinese participation in the 10 October Workers' Party of Korea anniversary celebrations last year had suggested that Beijing had been able to exert some moderating influence on the North.

This new development suggests China's influence is far weaker than might have appeared and that Kim Jong-un is committed to acting in defiance of his Chinese ally.

What can the international community do to temper the North's nuclear ambitions?

An emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council was speedily convened. There will be efforts to draft a resolution condemning the North's actions as a violation of international law.

This is likely to be coupled with fresh efforts to impose tighter economic sanctions against the North Korean government, particularly measures targeted against senior members of the government and the elite in Pyongyang.

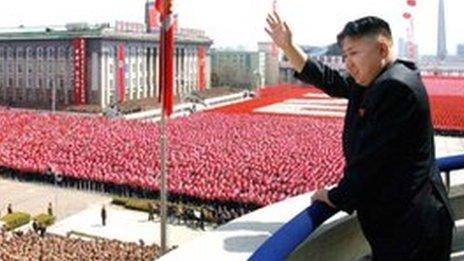

A picture from North Korean state TV showing leader Kim Jong-un signing the document for the hydrogen bomb test

However, sanctions in the past have had limited impact in retarding the North's nuclear programme.

A critical issue here is the reluctance of China, which provides the bulk of North Korea's food and energy assistance, to impose substantive pressure on the DPRK for fear of destabilising the Kim government.

Regime collapse risks generating an exodus of North Korean refugees across the 800-mile border with China, as well as a power vacuum in the North that might be filled by the US and its South Korean ally - two scenarios that Beijing is keen to avoid.

What are the long-term implications?

A North Korea that steadily enhances its nuclear and conventional force capabilities poses a growing strategic danger to the region.

The biggest worry is that through the latest test, the North will be able to miniaturise a nuclear warhead (a hydrogen weapon provides, pound for pound, more destructive clout than an atomic bomb) and in turn place it on a land or submarine-based ballistic missile capable of hitting South Korea, Japan or possibly the west coast of the United States.

For now, the evidence suggests that the North is some years away from developing such a capability, but the longer the North is able to test with impunity, the more fragile the strategic calculus in the region becomes and the more limited the choices of the surrounding powers when it comes to confronting the North Korean challenge.

North Korea and nuclear weapons

October 2002: North Korea first acknowledges it has a nuclear weapons programme

October 2006: The first of three underground nuclear explosions is announced, at a test site called Punggye-ri

May 2009: A month after walking out of international talks on its nuclear programme, North Korea carries out its second underground nuclear test

February 2013: A third nuclear test takes place using what state media calls a "miniaturised and lighter nuclear device"

May 2015: Pyongyang claims to have tested a submarine-launched missile, which are more difficult to detect than conventional devices

January 2016: North Korea says it has successfully tested a hydrogen bomb

Dr John Nilsson-Wright is head of the Asia Programme at Chatham House, and senior lecturer in Japanese Politics and International Relations at the University of Cambridge

- Published6 January 2016

- Published6 January 2016

- Published6 January 2016

- Published3 September 2017