Afghan city hopes for lift from Iran sanctions deal

- Published

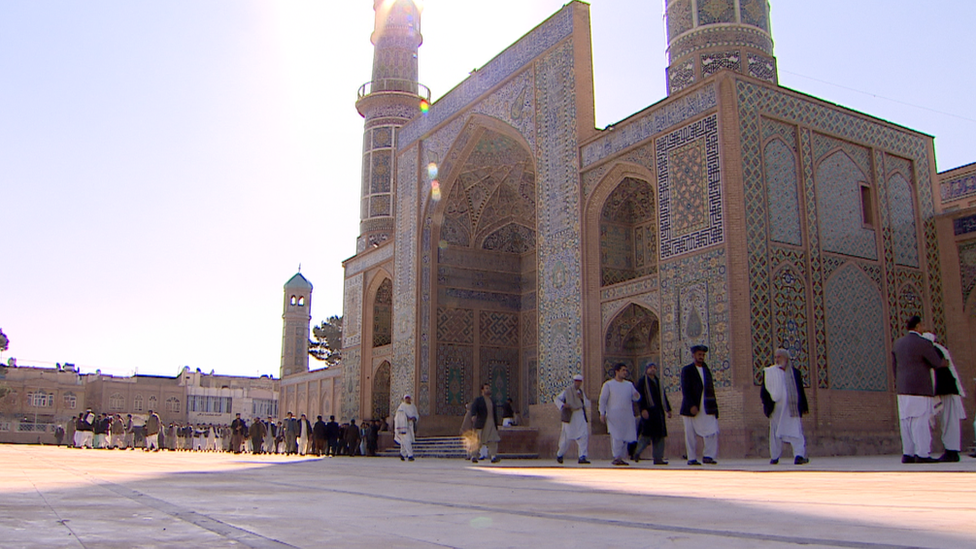

Herat has some striking buildings, including the Friday Mosque

If Afghanistan had a tourist industry, Herat would be top of the list of must-see destinations.

This magnificent city on the vast dusty plains that stretch westwards from the mountains of the Hindu Kush was once a staging post on one of the greatest trade routes of the world - the ancient Silk Road between China and Europe.

The city's blue glass and intricate carpets were celebrated across the globe.

But what used to be known as the Imperial Road is not so imperious now.

Sanctions on Iran have helped push what was once a busy thoroughfare to the very margins of the world economy.

The border never actually closed.

But the sanctions, particularly on banking, made doing business with Iran much more difficult.

The hope now is that Afghanistan - and the rest of the world - will benefit as the potentially vast Iranian economy opens up once again after more than a decade.

Billions of dollars of frozen assets will pour back into the country as the restrictions on moving money in and out of Iranian accounts are lifted.

The market continues to be busy

The Herat region has fallen on hard times

There is no shortage of deals to be done, Herat Chamber of Commerce head Hamidulla Khadam says.

"We have motorbikes, soft drinks, mineral water, paints, disposable crockery and plastic bags," he tells me, listing proudly just some of the products his city produces.

"The most important thing is that we will be able to transfer money via the banks, which we can't do now because of the sanctions," he tells me.

"That is likely to make it easier for us to buy Iranian goods, but more importantly it is also going to make Afghanistan a transit point for trade with other countries."

Possible downsides

Increased competition may mean local manufacturers will suffer.

But in Herat's busy market, the traders say virtually all the products they sell are already either made in or imported through Iran.

"If there is something we want to buy," one trader tells me with a broad grin, "we just smuggle it in."

Local craftsmen have a good reputation

Herat is famous for its glassware

Local people hope for a boost to trade

Lifting sanctions will make trade more straightforward, though.

"It should make the products I sell cheaper," he says.

In fact, the whole world is already feeling the effects of new competition from Iran.

Iran has the fourth biggest oil reserves in the world. And fuel prices are falling in anticipation of it opening up the taps.

But the hope is the benefits of lifting the sanctions will be more than just financial.

I chat with the commander in charge of the border, over a cup of saffron tea, a local delicacy (the desert honey is delicious too).

He says they will need to treble the number of staff to 6,000, to cope with the extra demand.

"Fewer people are going to want to join the Taliban," he tells me.

And that is a key part of the rationale of lifting the sanctions.

Economics and politics are closely entwined. And knitting Iran more closely into economy of this troubled region should knit it into its politics too.

Just a few years ago, Iran was regarded by the international community as a pariah state.

The hope now is that it can become a force for stability - another development that would benefit the entire world.

Herat:

Afghanistan's third largest city

capital of Herat province

in the fertile valley of the Hari River

has a number of historic sites, including the Herat Citadel, which dates from 330 BC and was saved from demolition in the 1950s, and the surviving minarets of the Mosallah Complex

governed by Afghan rulers since the early 18th Century

lies on the ancient trade routes of the Middle East, Central and South Asia

traditional gateway to Iran