Shan villagers feel force of Burmese army anger

- Published

Jonah Fisher looks round the rebel village of Wan Hai

The journey from Lashio to the rebel village of Wan Hai in eastern Myanmar takes about five hours. The area is off-limits to foreigners so our driver had taped darkened plastic over the windows and we hoped for the best.

He needn't have bothered.

At the Burmese army checkpoints none of the soldiers even stood up, let alone look into the car.

Despite intense fighting last year the presence of the rebel group known as the Shan State Army - North (SSA-North) is accepted here and vehicles pass through with minimal fuss.

The Shan State Army - North is not a signatory to a recent peace accord between armed groups and the state

The SSA-North is a long established part of the patchwork of armed groups in Shan State. The conflicts here tend to simmer not rage. For long periods army, militia and rebels have existed in close proximity, focusing more on drug production, logging and smuggling than fighting each other.

Its own history is littered with broken ceasefires, ignored promises and internal division. It is a fairly typical Burmese rebel group.

Back in 1989 the Shan State Army, as it was then known, signed a ceasefire brokered by Burmese General and Intelligence Chief Khin Nyunt. Along with some other rebels, the SSA stopped fighting in return for unfettered control over pieces of land."

Jonah Fisher says one challenge is that this is a war that's lasted generations

Its territory, now centred around the village of Wan Hai, spans a radius of about 15km (9.5 miles), though the rebels say their influence extends further. Over the years other factions, also using the name Shan State Army, sprung up. So observers appended "North" to try to bring some much needed clarity to this melange.

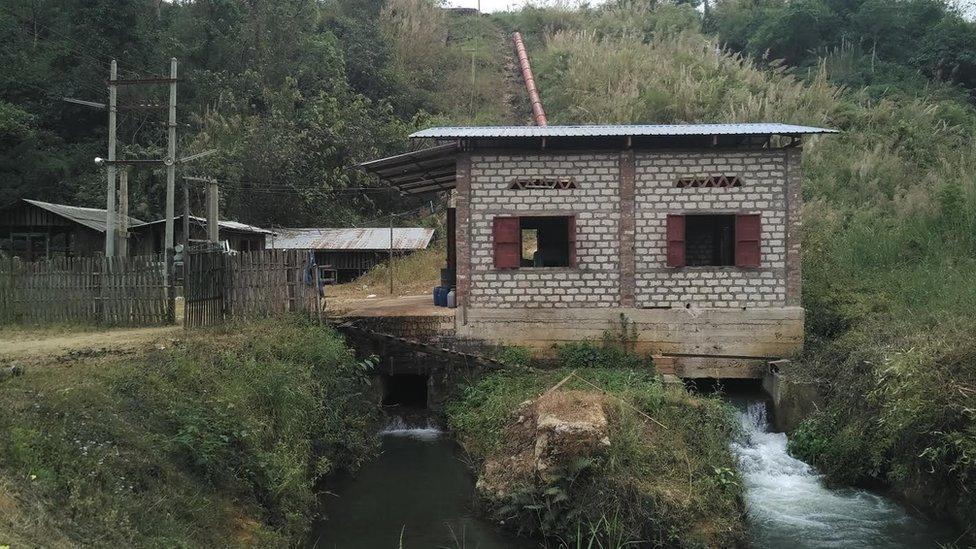

The SSA-North have run this area as a kind of "jungle government". There are schools, a basic hospital and - unlike most of Myanmar (also known a Burma) - 24-hour power, thanks to a hydroelectric turbine from China.

The turbine means the area has round-the-clock power

But it is no utopia for its residents. Villagers are "taxed" for supplies and families are expected to give up their young men to bolster rebel ranks.

A history of failed ceasefires

Early one morning we are taken to see the newest group of recruits being put through their paces, a motley bunch just three weeks into training.

Some are very young, others surprisingly old. Most of the drill focuses on how to perform a decent salute.

We are told that only once they have had a political education and reached what is called "Level Five" will they be given a gun and allowed to fight.

In 2009 that 20-year-old ceasefire negotiated by Khin Nyunt broke down when the government tried to force rebel armies to become part of a Border Guard Force.

The SSA-North emerged after the movement split following an earlier ceasefire

Many groups simply refused to join, but the SSA-North split, with some brigades agreeing to become part of this new force. Those that refused remained in Wan Hai and after more clashes another local ceasefire was signed in 2012.

It then joined nationwide talks alongside 15 other armed groups aimed at brokering yet another ceasefire. This time the idea was that all rebel groups could engage in meaningful talks to address the root cause of these conflicts.

But that final ceasefire proved elusive until Myanmar's outgoing President Thein Sein decided to go for broke.

He set a deadline of 15 October 2015 and called all rebel groups to the capital, Nay Pyi Daw. Of the eight groups that showed up, none were particularly active. The SSA-North was among the eight who refused. The SSA-North was among the eight who refused.

As hollow applause rang out at the signing of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement the Burmese army took its frustration out on villagers in rebel areas near Wan Hai.

For several weeks mountaintop villages were shelled and helicopter gunships used in clashes with the SSA-North. The rebels say 30 of their fighters died and claim to have killed hundreds from the Burmese army. The numbers are impossible to verify.

Several thousand villagers from ethnic minorities fled their hilltop homes to camps deeper in rebel territory. One of them was a Palaung woman called Nai Song.

Nai Song says she has been left with nothing after the fighting

We found her outside the bamboo hut that's been her home for the last three months and she agreed to take us back for a quick look at her village.

We travelled on motorbikes and then on foot up along narrow rocky paths to reach Kong Nime. From the mountaintop you could just about make out the camp where the village's residents now squat.

'I cry every day'

Before the Burmese army attacked Kong Nime there were about 500 people living here. Now there are just a handful, sent back to look after the livestock. They told us that at night they are too scared to stay in their own homes so huddle together.

When the villagers fled the shelling soldiers from the Burmese army moved in, taking everything of value. Nine houses were burnt to the ground.

Much of Kong Nime has been destroyed by the army

Nai Song says she was once one of Kong Nime's more affluent citizens, but not any more. When the fighting started she had just purchased 1m kyat (about $800) worth of supplies on credit.

"Three containers of cooking oil, three containers of alcohol, three containers of kerosene, all gone," she begins to list the things that have been taken.

Upstairs she points out some grotty blankets she rescued and washed from the street. Then she brings out a battered kettle and starts to weep.

"This all I have here now - and there's not even a lid for my kettle," she sobs.

Another woman called Ba La also came with us back to Kong Nime.

"All our medicine has been lost," she says. "We had five packs of medicine carried by five motorcycles, bought on credit for about 500,000 kyat. I've got no money to pay back."

Ba La has suffered at the hand of the Burmese army before. Back in 2011 her son Aikor was abducted by Burmese soldiers and she hasn't heard from him since. For years the Burmese military has been taking boys from ethnic minorities to use as porters.

What's changed?

Efforts to bring peace to Myanmar have been built on the assumption that the Burmese army is changing. That its leaders really want a lasting, just peace, and despite having fought against federalism for decades they are now committed to devolving power.

Large numbers of people have been displaced in the army offensives

The evidence on the ground suggests that very little has changed. The Burmese army has been looting and burning villages just like Kong Nime for decades. Elsewhere in Shan and Kachin state it is continuing to attack other non-signatory groups.

Even among those who were persuaded to sign the so-called Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement there is a strong suspicion that the army just sees the peace process as a way to force the rebels to disarm and effectively surrender.

It was a view reinforced in Nay Pyi Daw two weeks ago when the army's Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing bluntly told the signatories that he wanted a timetable for their demobilisation.

It didn't go down well.

So what then are the chances of the new government lead by Aung San Suu Kyi breathing fresh life into the fractured negotiations?

Having made ethnic peace her number one priority, she's promised to try to get all the rebel groups back into the process. But there are clear limits to her power.

"She will try," General Hsay Htin, one of the SSA-North's veteran commanders, told me with a shrug.

"But she will have a hard time because her main obstacle is the army."

- Published15 October 2015

- Published15 October 2015

- Published26 May 2023