How Tajikistan's President Emomali Rakhmon consolidated his power

- Published

Tajikistan's President Emomali Rakhmon has been in power since 1992

On 22 May, the people of Tajikistan will vote in a popular referendum on constitutional amendments that could effectively make leader Emomali Rakhmon president for life.

The bill removes the presidential term limit for "the leader of the nation", the title given to Mr Rakhmon. He is currently serving his fourth term - and has used previous constitutional changes to get around the two-term limit.

His current term, which is supposed to be the last one, will end in 2020. But if the suggested amendments are adopted, he will be able to serve as many terms as he wishes.

And Mr Rakhmon normally has no difficulty in getting re-elected, although according to international observers, most elections in Tajikistan haven't met democratic standards.

Emomali Rakhmon has been in power since 1992, and has managed to increase his power by cracking down on political dissent and freedom of expression.

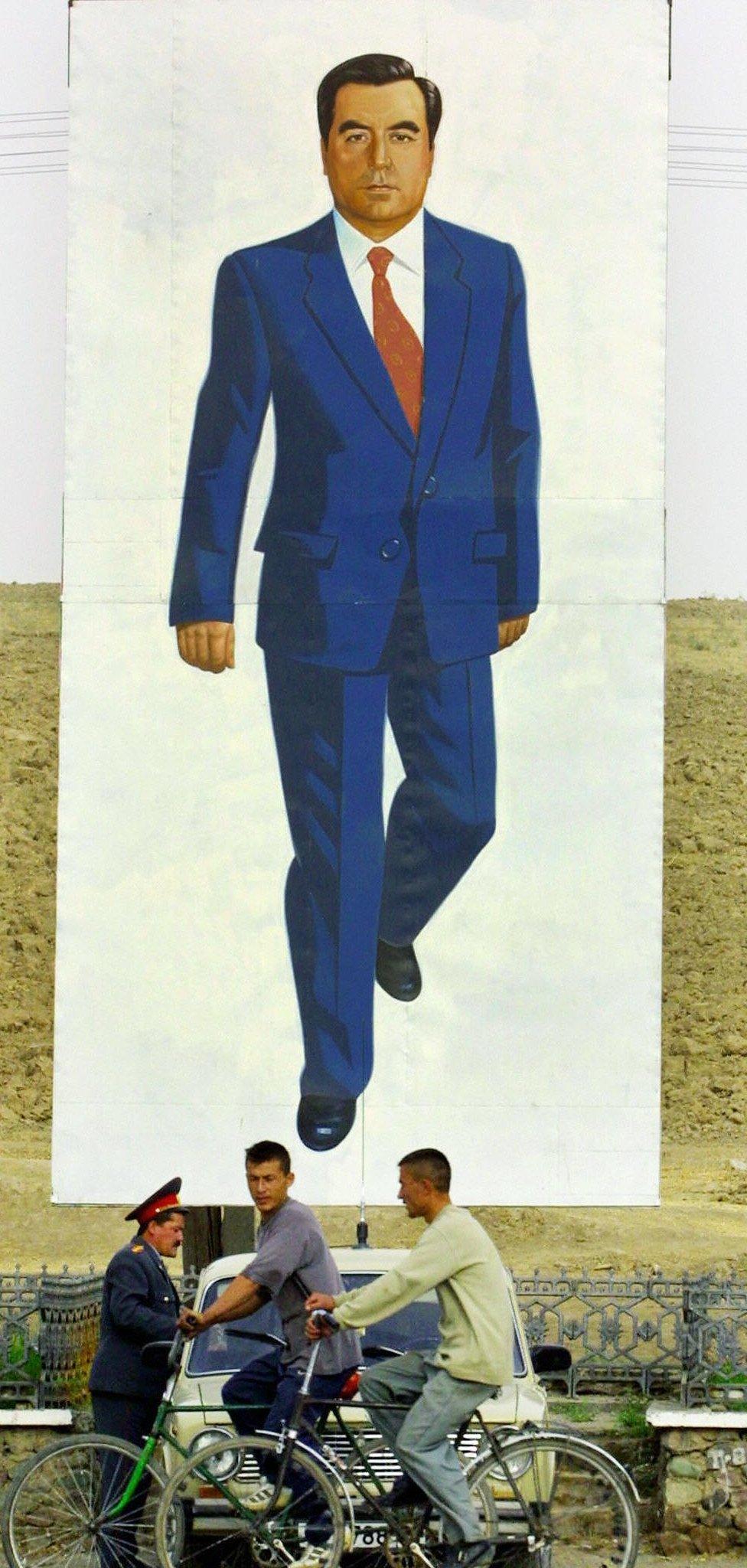

Mr Rakhmon has substantial public support - and his rather serious face can be seen on posters across Tajikistan.

People sing his praises and dedicate poems to him. And huge crowds turn up to presidential rallies - although attendance is obligatory for state employees.

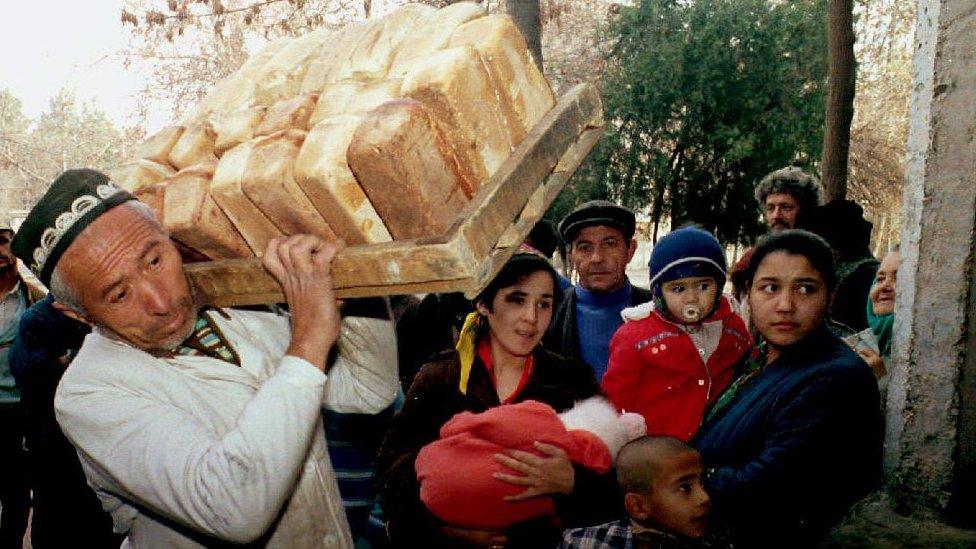

Mr Rakhmon's supporters are grateful the civil war of the 1990s is over - but life is not easy for most Tajiks.

Tajikistan is the poorest country among post-Soviet states, with more than a third of its population living below the poverty line.

Many Tajiks are forced to go to countries like Russia to find work, and their remittances make up half of the country's GDP.

In contrast, the president's family members and close relatives are some of the richest people in the country, running major businesses and holding top government jobs.

How common is it to appoint family members to senior posts in Tajikistan?

Mr Rakhmon's daughter Ozoda was recently appointed as the head of the presidential administration, while his son Rustam Emomali is the director of the anti-corruption agency.

Many believe Rustam is being groomed to become his father's successor - and this view appears to be supported by the upcoming referendum.

One of the suggested changes proposes lowering the age limit for presidential candidates from 35 to 30. This means that Rustam Emomali, who is 29, will be able to run for presidency in the next elections in 2020 should it be necessary.

More than a third of Tajikistan's population lives below the poverty line

The constitutional amendments have been backed by the government and the courts.

Umed Davlatzod, deputy minister of economy, said the changes would "provide guarantees in protecting human rights and freedoms, and attract the youth into the political life".

The constitutional court, meanwhile, has ruled that the proposed amendments "will strengthen the constitutional regime" and "reflect the democratic development" of Tajik society.

However, critics say the proposals reflect cementing authoritarianism rather than democratic development.

Many Tajiks migrate to Russia to find work

Muhiddin Kabiri, a self-exiled leader of the main opposition Islamic Renaissance Party (IRP), told the BBC that the referendum is against democratic principles since it will ensure that power remains in one hand.

"The elite want to secure their rule for good," he said.

He claims his party was shut down last year because they were the only group that "could prevent one-man or one-family rule".

The constitutional amendments put to the referendum propose to ban any parties based on religion, making the Islamic Renaissance Party illegal.

That would end a peace deal agreed back in 1997.

Bloody history

After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, a civil war broke out in Tajikistan as different groups started competing for power.

Tajikistan became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991

To end the bloodshed, the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), an alliance of political parties and local strongmen in which the IRP played a key role, signed a peace agreement with President Rakhmon.

According to this agreement, the IRP and other opposition groups became legal and Mr Rakhmon had to share power with them. The opposition was supposed to have a third of all cabinet seats.

But over time, UTO members were pushed out of the government.

Over 20,000 people were killed and 600,000 displaced during the five-year civil war

Key opposition figures fled the country, fearing persecution - but also faced threats abroad.

Politician Mahmadruzi Iskandarov, who was in Russia, was brought to Tajikistan against his will in 2005 and jailed for terrorism.

Another activist, Umarali Quvatov, was killed by an unidentified gunman in Turkey in 2015.

Those who have tried to challenge the president from within Tajikistan have also faced difficulties.

Zayd Saidov, a former minister of industry and one of the richest men in Tajikistan, was arrested in 2013 shortly after he announced his plans to start a new opposition party.

Lawyer and human rights activist Oynikhol Bobonazarova tried to compete in the 2013 elections

And human rights activist Oynikhol Bobonazarova, who was nominated by the opposition as a presidential candidate during the 2013 elections, and who clearly posed little threat to the incumbent, says she was forced out of the race,

Ms Bobonazarova failed to get enough signatures to enrol as a candidate - which she blamed on the police harassing her supporters and campaign activists.

So, is Mr Rakhmon likely to become a de factor president for life, until he decides to hand power to his son?

Tajikistan is officially a democracy, and the changes still need to be accepted on a referendum.

But in Tajikistan elections and referendums rarely deliver surprise results, so few observers doubt that the popular vote will be overwhelmingly in favour of the proposed changes.

- Published30 October 2024