Why did Pakistan keep hard-line mourners off air?

- Published

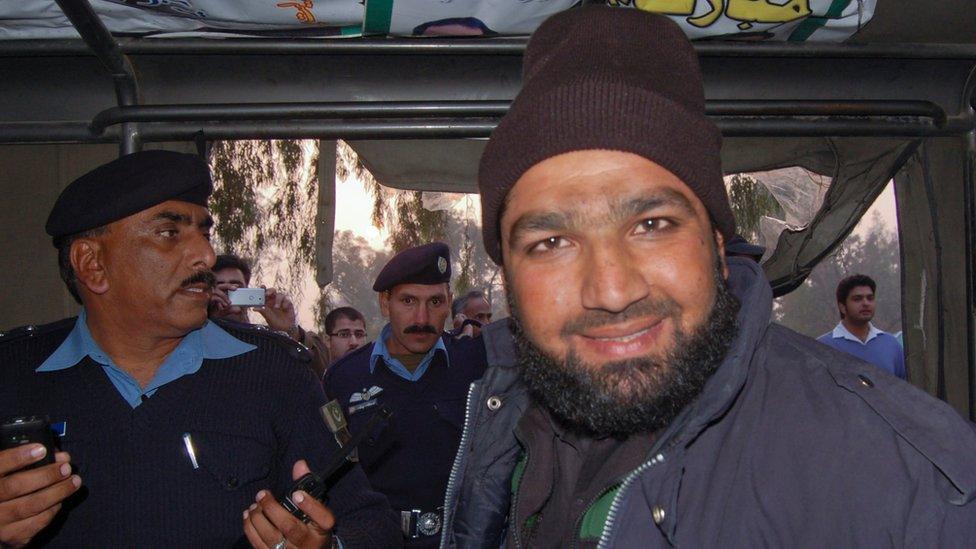

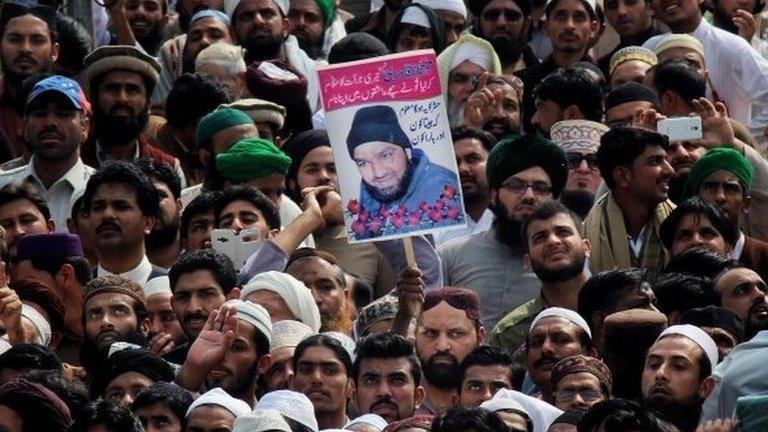

Supporters of Mumtaz Qadri protested at his execution but the protests were quieter than expected

When news of Mumtaz Qadri's execution hit the television screens on Monday morning, the Pakistani nation recoiled into long-familiar defensive mode.

Parents kept many children home from school, and some people stayed away from work. Across the country, Pakistanis were glued to their television sets in anticipation of riots on the streets by those who revered the former bodyguard who killed Punjab governor Salman Taseer for advocating blasphemy law reform.

But what protests there were were sporadic and not well attended. And though they burned tyres and beat up a couple of journalists, the protesters showed no inclination to target the security forces.

The mood of the crowds at Tuesday's funeral for Pakistan's most notorious death row prisoner was equally restrained. More importantly, news anchors of dozens of Pakistani television channels, who would normally be hysterical at such a development, seemed not to notice.

Instead, crime in Karachi and hints of a possible cancellation of an upcoming India-Pakistan cricket match dominated the headlines. So why the media silence when there was a golden chance to boost ratings?

"Obviously, they have been sent a piece of advice by an authority they can't ignore, and that authority is definitely not the political government," says Ayesha Siddiqa, a defence and political analyst.

Who is pulling the strings?

For most in Pakistan, the only authority that has been able to chastise a once-unbridled Pakistani media has been the military.

In an unprecedented move in April 2014, it was able to force one of the largest TV news channels, Geo, off air after it accused the ISI intelligence service of orchestrating an attack on one of its top journalists. The ban was "fronted" by the civilian-led media regulatory authority, Pemra, but observers saw the military pulling the strings behind the scenes.

On Monday, the day Mumtaz Qadri was hanged, Pemra held a meeting in which it threatened with closure TV channels that covered "events that glorified criminals". The message for Qadri's supporters was clear.

Mumtaz Qadri (right) was arrested in 2011 and charged with the murder of Punjab governor Salman Taseer

But Pakistan's hard-line Islamists were not always like this.

In 2012, a conglomeration of religious forces styling itself as the Pakistan Defence Council (PDC) took the country by storm, holding big rallies in every corner of the country to sell a virulent anti-American and anti-Indian agenda.

In the words of Dawn newspaper's Cyril Almeida, external, the campaigners included "jihadists, sectarian warriors, orthodox mullahs, Islamic revivalists, all banding together… to defend Pakistan".

The PDC showed no restraint at its rallies and Pemra did nothing to enforce its so-called responsible journalism guidelines.

The military establishment was widely seen by analysts as having played a role in the PDC, for two reasons: to deflect American pressure for action against the Taliban, and to frustrate the then government's plans to extend preferential trading status to India.

Is the military apolitical?

In 2014, thousands of activists loyal to former cricketer Imran Khan and a firebrand cleric Tahirul Qadri occupied Islamabad's high-security Red Zone for months, paralysing the government.

On one occasion they broke into the offices of Pakistan Television and put its various channels off air for several minutes. The military refused to intervene, claiming it was an "apolitical" institution which supported democracy.

The protests were seen by many as having had a nod from elements in the security establishment, again for two reasons - forcing the newly inducted government of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to back down from a treason case it lodged against former army chief Pervez Musharraf, and to frustrate its aspirations to normalise relations with India, which had been one of Mr Sharif's main election slogans.

So what has changed now?

Analysts point out that with Nato's planned drawdown in Afghanistan, the Pakistani military is reordering its security policy to ensure its continued influence in Afghanistan and to prevent what many pro-establishment analysts describe as "Indian hegemony".

On the heels of this development has come the proposed $46bn economic corridor the Chinese are planning to build through Pakistan. This investment is seen by many as more than making up for the drying pipeline of American aid for a military that has been holding its own within a chronically cash-strapped economy.

In order to fully benefit from this investment, forces that can cause internal chaos must be quietened.

Many say this is what has been on display in Rawalpindi this week. Apart from paving the way for Chinese investment, this also sends out a message to the international community that Pakistan has the wherewithal to control militancy when it wants, says Ayesha Siddiqa.

But since there are still no signs a similar call has also been given to groups focused on India and Afghanistan, Pakistan is likely to continue to dabble in the tricky business of separating "good" militants from "bad".

- Published1 March 2016

- Published29 February 2016

- Published9 January 2012

- Published14 January 2011

- Published5 January 2011