The godmother of manga sex in Japan

- Published

Manga is hugely popular in Japan but critics fear some of it amounts to exploitation

A recent UN report weighed into a debate that provokes intense controversy in Japan, by including manga in a list of content with violent pornography. The BBC's Yuko Kato went to meet one of Japan's leading female manga artists, Keiko Takemiya, seen as the woman who opened the floodgates to sexually explicit manga.

Some readers may find some of the sexual details that follow disturbing.

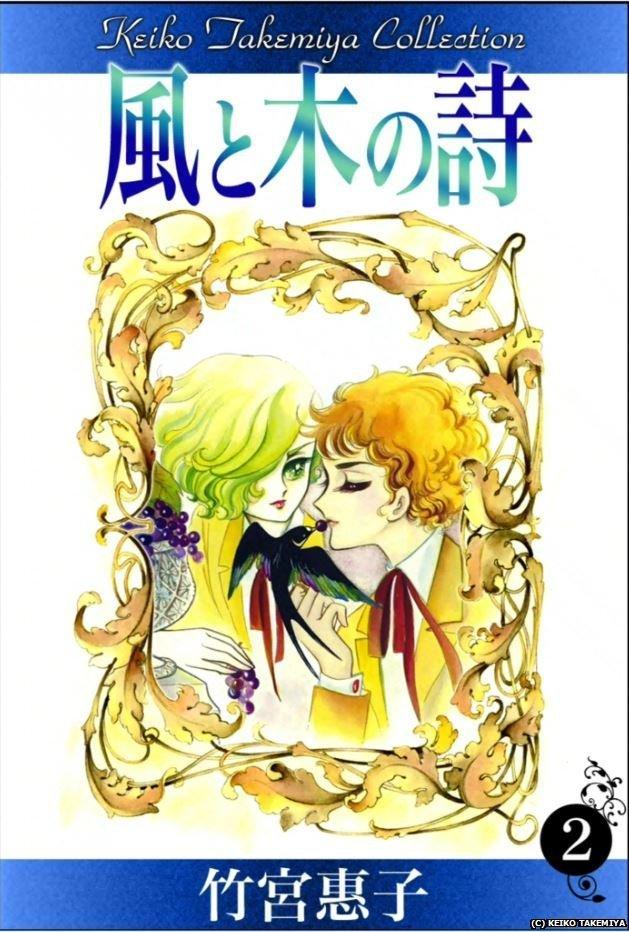

In 1976, when she was only 26 years old, Keiko Takemiya began a comic series that proved to be a ground-breaking moment for Japanese manga. Called Kaze to Kino Uta (The Poem of Wind and Trees), it opens with two naked teenage boys in a 19th Century French boarding school lying on top of each other, post-coital.

The series centres on one of those boys and another new boy. Gilbert, who was abandoned by his parents but raised by his uncle, has experienced rape and incest, and spends his time as a sex toy for the older boys and staff. He then meets Serge, the dark-skinned son of an aristocrat, and the subject of bigotry.

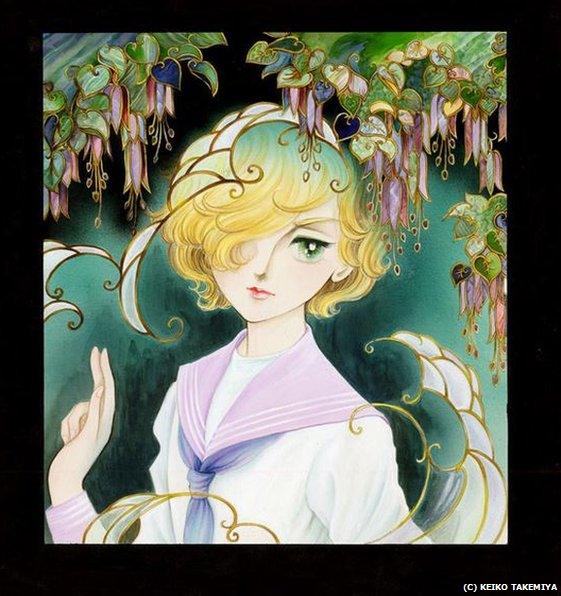

Cover art for Kaze to Kino Uta (The Poem of Wind and Trees)

It addressed and broke almost every taboo thinkable when it was published in a weekly girls' manga magazine.

"In those days everything was opening up. Freedom was in the air... I wanted to explore and write about love without boundaries, love in different kinds of shapes and forms, whether it was between man, woman, child or an old person," Ms Takemiya says.

Until the early 1970s, popular manga for girls in Japan was mainly about ordinary teenagers finding boyfriends, the trials and tribulations of everyday life. It was a time when a heterosexual kiss between consenting adults in manga was considered racy. Anything more intimate was simply hands held on bed sheets, flickering candles. Burgeoning sexuality was a teenager turning beet red when her hands touched the boy of her dreams.

Ms Takemiya was one of a pioneering group of female artists who made manga a genre many consider now worthy of literary criticism, heavily influenced by Western authors like Herman Hesse, Bram Stoker, Dumas and Dostoyevsky, drawing on their perennial themes of love, hate, life and death.

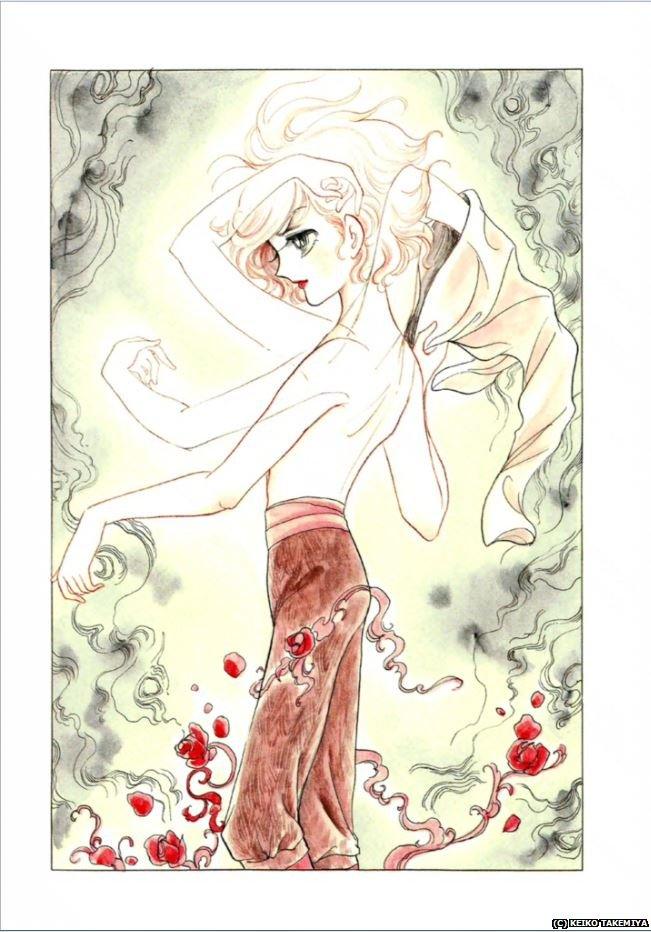

Gilbert from Kaze to Kino Uta

When asked how she got her editor to agree, she says: "I couldn't.... not for years." She also had to persuade her editors she was popular enough among her teenage readers to be worth the risk and that took years of honing her skills.

"I had to earn the right to do Kaze to Kino Uta," she said.

At that time girls' manga was still a niche market. In the pre-internet age, teenagers could keep Gilbert and Serge hidden from adult eyes. It depicts, if not graphically or gratuitously, not just physical love between two boys, but rape and incest. At one point in the series the victim is a nine-year-old boy.

In doing this, Ms Takemiya herself admits, she may have opened the door to sexual expression in Japanese manga, and it grew from something virtually non-existent to something the UN now considers could be a threat to the welfare of women and children.

Keiko Takemiya, one of the most influential figures in Japanese girls' manga, is now president of Kyoto Seika University

In 2004, when Japan revised the law against child prostitution and pornography, it was asked if the portrayal of fictional children should be included in the ban. This provoked a fierce debate about sexual expression in manga.

When the Tokyo government tried to go down the same path six years later, Ms Takemiya, then dean of the faculty of manga at Kyoto Seika University, of which she is now president, protested vehemently. She called it an attempt to clamp down on freedom of expression and pointed out her book, seen as a classic, would have been banned.

Why hasn't Japan banned child-porn comics?

It didn't go ahead, but the battle lines were drawn and it persists today.

On one side are those who see the regulation of sexual violence in manga as a means to protect the vulnerable, arguing it encourages real life crime. On the other side are those who object to excessive state control over freedom of expression. They say there is no statistical evidence, external to prove the link. They say the graphic depiction of genitalia, even in fiction, is already banned under Japan's penal code.

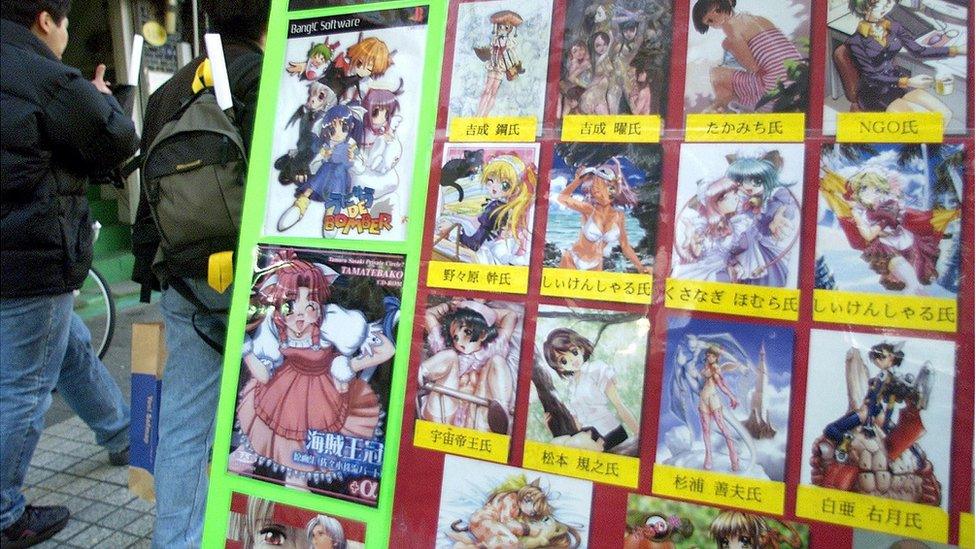

Many see the more explicit manga not as an issue of freedom of expression, but gratuitous exploitation

In March, the UN Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography Maud de Boer-Buquicchio, submitted a report to the UN Human Rights Council, external, citing a US State Department report which calls Japan "a major producer of sexually exploitative representations of virtual children".

Whether or not the depiction of "virtual children" in manga is violating an actual human right is the crux of the issue. A lot of the material that draws criticism does not aspire to the literary heights of Ms Takemiya's work and critics say it exists purely for titillation. Many believe that even if it is fiction, it should be regulated.

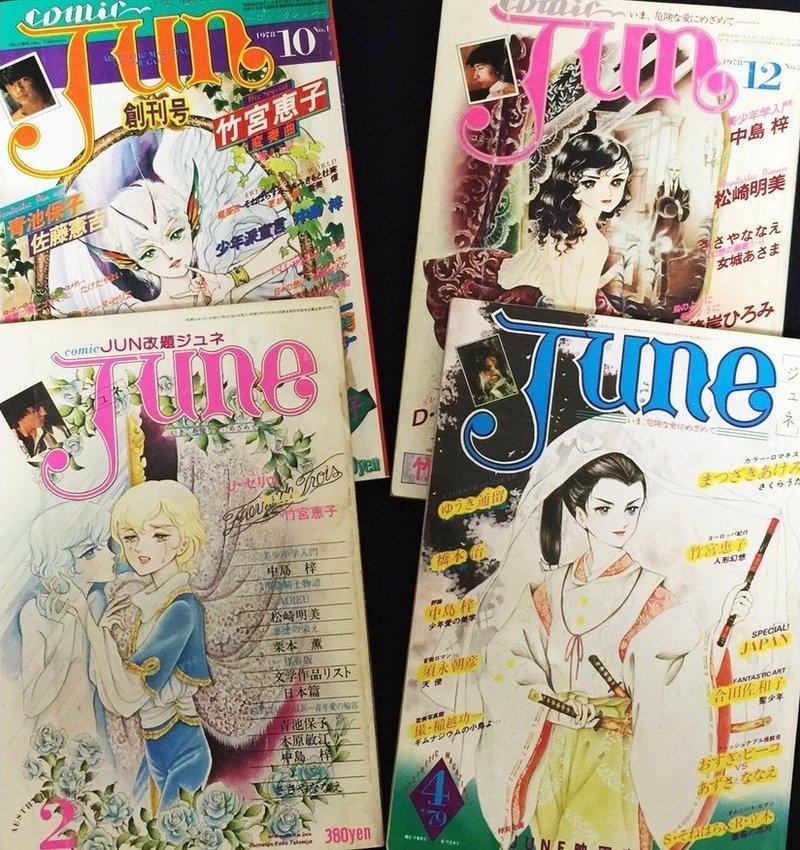

Takemiya was also the main cover artist for the popular magazine that spearheaded the "beautiful boys" manga movement in the late 1970s.

Ms Boer-Buquicchio says she is aware of the importance of striking the right balance for freedom of expression but that the rights of the child should not be "sacrificed at the expense of powerful and lucrative businesses". She points out that "any pornographic representation of a child," real or not, "constitutes child pornography".

This is a view Yukari Fujimoto, manga expert and professor at Meiji University, does not share. She feels the UN is targeting manga on false assumptions.

A scene with Gilbert and Serge from Kaze to Kino Uta

She asserts that while the intention may be to protect women and children, the effects will be counterproductive as manga has given women an outlet for their own sexual expression.

"A ban on sexual violence in manga would effectively be a ban on the hard-won achievements and expression of female artists. Banning artistic expression will neither change or improve reality."

For other observers, it is self-censorship that is the worry as there is precedent for this in Japanese society.

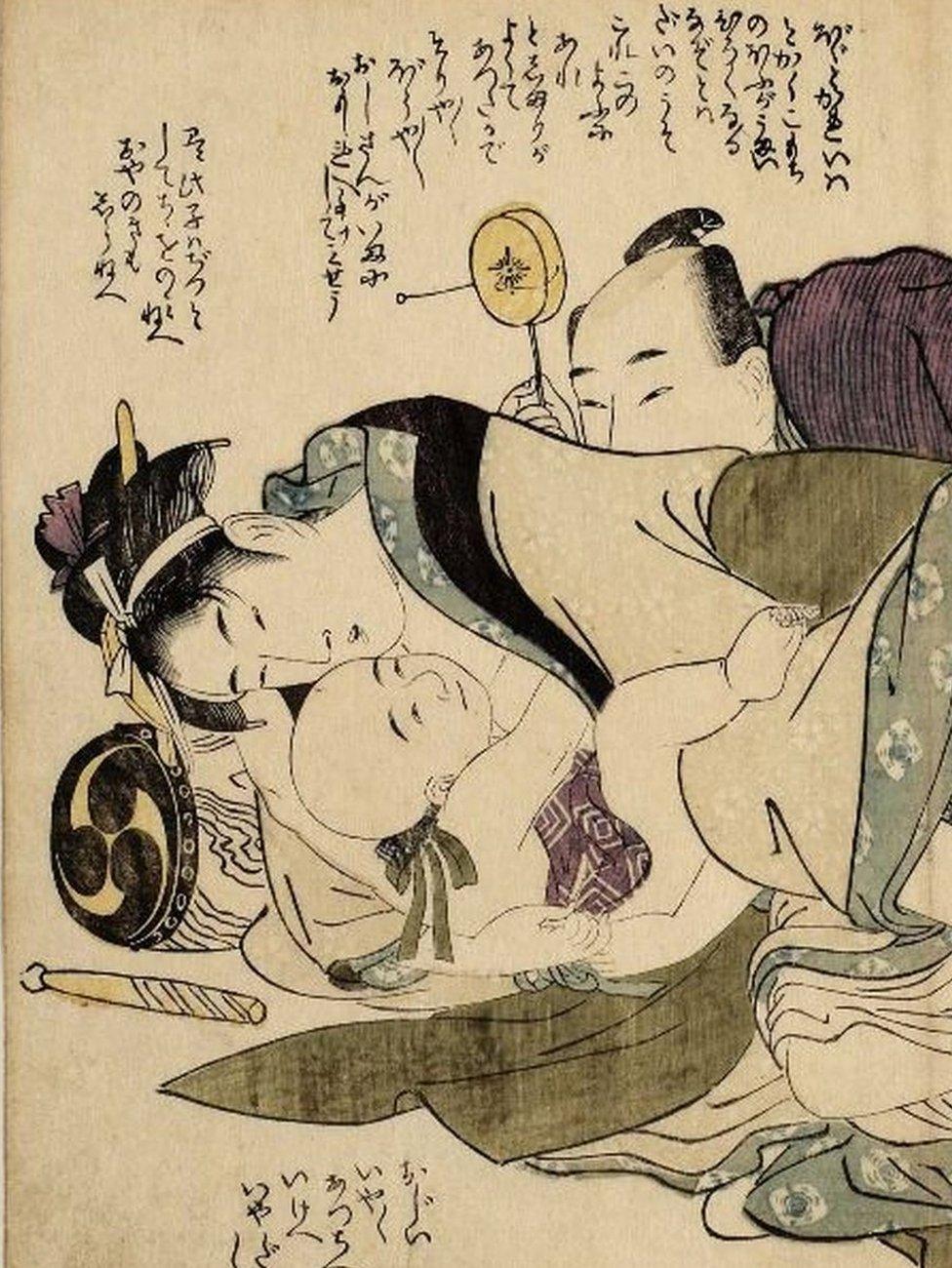

Writer Mari Hashimoto, an expert on Japanese classical art, points out that the first major exhibition of the classical erotic shunga (literally, "spring pictures") could be held in Japan in 2015 only after the success of major international exhibitions., external

In shunga, Ms Hashimoto explains, it was standard to depict a small child next to a couple having sex. It was an expression of normal life in a particular historical context. But with modern notions of seemliness, these pieces were discreetly removed from exhibition catalogues.

She says when artists, curators and critics "are made to feel they have to restrain themselves... this will cause culture to atrophy".

A section of a shunga depicting a couple and a baby from Ehon Toko no Ume (Picture book: Plums in Bed) by Kitagawa Utamaro, Courtesy of the International Center for Japanese Studies.

The public reaction in Japan is divided. Some are passionate about free expression, others draw the line between what they see as artistic quality and what they judge to be purely smut, and others are not interested. There is no national consensus.

This may be in part because the debate is framed somewhat differently in Japan. The concept of "kawaii" or "cuteness" dominates Japanese popular culture, from merchandise to pop music, and so the Japanese public could be argued to be less squeamish about the use of child imagery than a Western audience might be.

Keiko Takemiya is not apologetic about including troubling portrayals of sexual violence involving children.

Gilbert from Kaze to Kino Uta has become an iconic character in Japanese girls' manga

"Such things do happen in real life. Hiding it will not make it go away. And I tried to portray the resilience of these boys, how they managed to survive and regain their lives after experiencing violence."

This was the late 1970s when such things were not talked about in mainstream media, let alone girls' manga. Ms Takemiya recalls receiving a letter from one of her readers who said she had been raped by her father.

"She never thought something like that happened to other people, but reading my manga told her that she wasn't alone and that saved her," she recalls.

Ms Takemiya doesn't know if the letter was authentic, but she staunchly believes denying human nature is not the answer.

"I may have opened a Pandora's box of sexual expression, but the box had to be opened for Hope to come out."

- Published7 January 2015