Pakistan's counter-terror offensive after Lahore attack

- Published

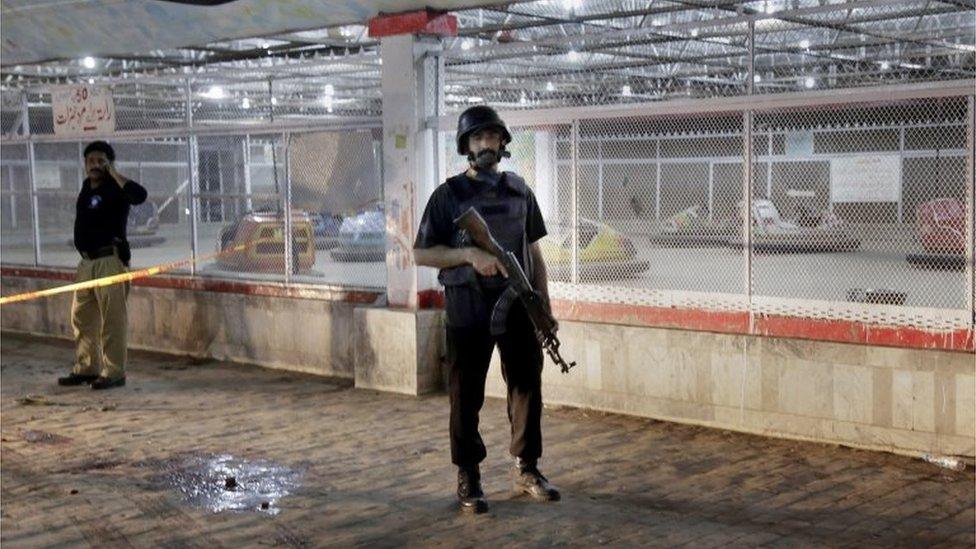

Police are guarding the park in Lahore - but the military has led the crackdown

Pakistan says more than 200 people have been detained for questioning since the Easter Sunday bombing that killed at least 72 people in Lahore. Arms and ammunition have also been recovered, the military says, in a sweeping crackdown.

Who has been arrested?

The exact number of detainees is not yet known, but an estimated 200-300 suspects are thought to have been taken into custody so far. Their identities have not been made public. Military spokesman Asim Bajwa described them as "suspect terrorists and their facilitators".

Punjab, and especially the south of the province, has been a nursery for several India-focused groups such as Laskar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad, and for sectarian groups like Laskar-e-Jhangvi. In fact, the initial arrests after the bombing were made in the southern Punjabi district of Muzaffargarh. The men picked up were relatives of a man investigators wrongly suspected of being the suicide bomber.

Where have raids taken place?

The crackdown started on Sunday night, soon after a meeting of the military top brass at which it was decided to clean up known hideouts of militants in Punjab. Economically backward, southern parts of the province have traditionally been the main catchment area for religious groups. This is due to the proliferation of religious seminaries there that provide free education, boarding and meals for students. Central Punjab, the political and economic power base of the country, is more affluent.

Initially the military targeted militant cells in Lahore and Faisalabad in central Punjab, and in the southern district of Multan. Subsequently there were joint raids by the military and police in Gujranwala in central Punjab, and the southern districts of Khanpur, Liaquatpur and Sadiqabad.

Investigators searched through debris for evidence while raids got under way

Nearly all the Pakistani extremist groups own and run their own seminaries across Punjab. These seminaries are used by these groups as their offices, contact points and residential quarters, and most of them are known to the civil and military intelligence services.

Did the military ask permission before launching raids?

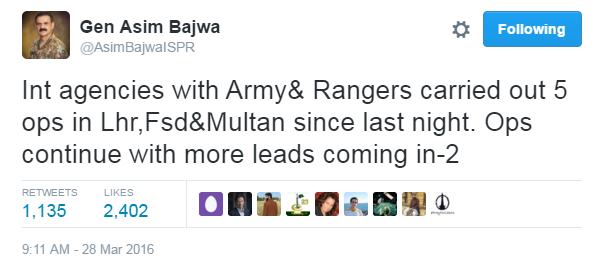

The news of the first five raids was broken by the main spokesman for Pakistan's powerful military in three tweets, external.

The fact that there was no mention of the presence of police in those raids raised eyebrows. Until now, raids in Punjab have normally been planned on the basis of intelligence provided by the military or civilian agencies, and have been led by the police, with the paramilitary Rangers providing back-up. The provincial government has had the prerogative to choose targets. But apparently none of this was in evidence on Sunday night.

On Tuesday, the provincial minister for information claimed at a press conference that the government also had the prerogative to determine "which, and how much, force should hit a certain target", implying that actually it was the political leadership that called in the army in Punjab. But for the moment, few are convinced, and there is a lingering impression that the military has forced the government's hand.

Does the PM support the crackdown?

Mr Sharif cancelled travel plans to stay in Pakistan after the bombing

Nawaz Sharif's early political career was shaped under the influence of the military regime of Gen Ziaul Haq which Islamicised Pakistani laws, promoted an Islamic public narrative and oversaw the proliferation of private religious militias. His PML-N party continued to support jihad (holy war) in Afghanistan during the 1990s and drew largely on a conservative religious vote bank in Punjab.

But the military operation to drive militants out of Waziristan and the massacre of children at a school in Peshawar have gradually pushed the party's right-of-centre politics more towards the centre. This the party has accepted more as a fait accompli than a voluntary shift. Up to now Mr Sharif's government has been resisting a military operation in Punjab, fearing that it will lose its grip on its home province, which is also the most populous in Pakistan.

It will have taken note of Karachi, where military action has rendered the Sindh provincial government largely irrelevant in day-to-day affairs.

How serious is Pakistan about tackling extremists?

Pakistan has been long accused of nurturing militant groups as an instrument of foreign policy. It has also promoted an Islamic public narrative in order to support these groups. On the domestic front, the groups and the narrative are seen by many as having helped the military keep secular political forces at bay. But the Nato drawdown in Afghanistan and Chinese plans to invest billions of dollars in infrastructure projects in Pakistan seem to have changed the equation.

Religious hardliners have been protesting in Islamabad

The Pakistani army started the long-demanded operation in North Waziristan aimed at wiping out militant sanctuaries that had existed there since the early 1980s. It was also instrumental after the Peshawar school attack in getting the political leadership to approve a National Action Plan which promised an indiscriminate crackdown against militants.

But it has continued to ignore the existence of anti-India and anti-Afghanistan groups on its soil, citing troubled relations with India. The military, and its civilian apologists, say they don't want their ranks to spread too thinly. So for the moment, only those groups which have an expressly anti-Pakistan agenda are likely to be targeted.

- Published29 March 2016