Have we fallen out of love with elephant rides?

- Published

Elephant rides and other animal encounters have long been a staple of the Asian backpacking experience. But with steady reports of animal cruelty, the BBC's Anna Jones asks whether tourists are starting to turn their backs on such adventures.

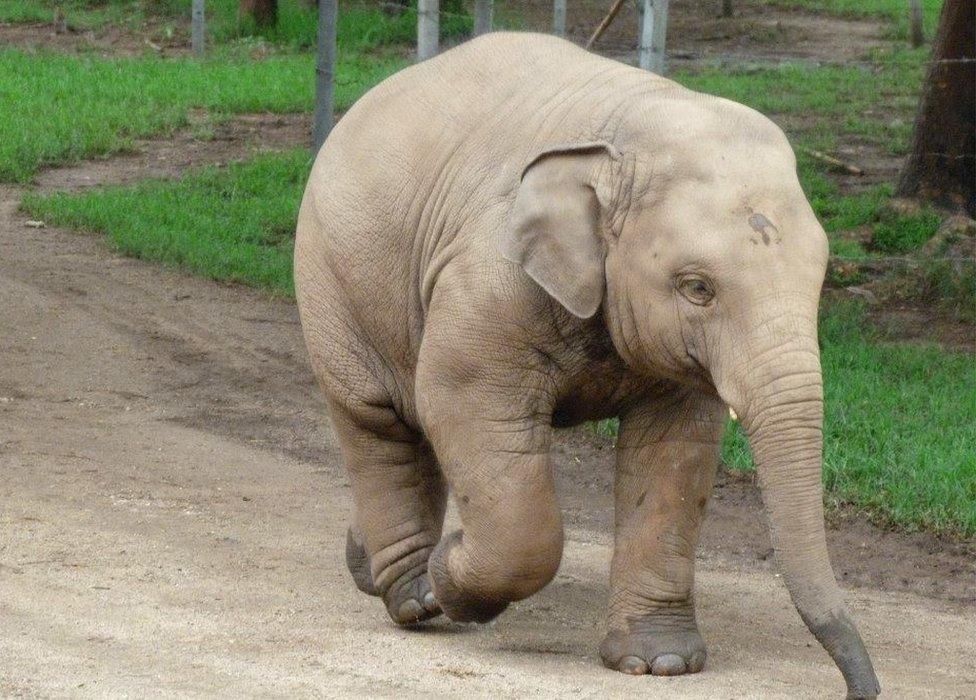

I've done it. Like so many tourists to Asia, I have ridden an elephant.

It was many years ago while backpacking in Thailand, and I recall it as a mostly uncomfortable experience, sliding around a wooden seat on a purpose-built track through a sticky jungle.

That's me in the picture above.

There was also a degree of moral discomfort. To my untrained eye, the elephant seemed fairly uncomfortable too.

The mahouts - the handlers - carried curved spikes to keep the elephants in line as we trekked around that track for quite some time.

When I asked if the hooks hurt as they hit the elephants on the forehead with the spikes every now and again, they said no. Their skin was too thick, I was told.

But on a more recent visit to Cambodia, the guide on our bus asked if anyone wanted to ride an elephant up to an Angkor Wat temple. The response from everyone was a resounding no.

There is still a healthy market for elephanteering and those tour operators say they prioritise the welfare of the elephant

Then this week, an online petition calling on Cambodia to totally ban elephant rides was launched, and has already exceeded its target of 50,000 signatures.

It was driven by the news that an elderly elephant had collapsed and died while shuttling tourists along that same Angkor Wat route in 40C heat.

'No cruelty-free rides'

This elephant's death has prompted thousands of people to sign a petition against the animals' use in tourism

Elephants have never been truly domesticated. They are captive wild animals, and if they decide to turn on handlers or riders, it can be deadly.

Operators generally reassure tourists that they look after their elephants well, but critics say there is simply no way rides can happen humanely.

Procuring an elephant to use in logging or tourism often means taking it from the wild as a baby and literally breaking its spirit, in an often brutal process.

Years of carrying tourists takes its toll on an elephant's body. An Asian elephant is meant to have a peaked back, for example, but heavy saddles can flatten it.

They risk dislocated legs, die younger than they would in the wild and, their advocates say, the inability to behave naturally takes a severe toll on these highly sociable and intelligent animals' mental health.

Photos with tigers often appear on dating profiles, but are they ethical?

Alyx Elliott, UK head of campaigns at World Animal Protection, says she has noticed "a significant shift in public attitudes".

"You only have to look at the public comments to TripAdvisor on social media to see people's shock and outrage as they learn about the cruelty that is involved when elephant rides are offered."

But it's also clear from TripAdvisor, a travel review portal, that there's still enthusiasm for such elephanteering.

"Elephants are trained to pose for pictures and make noises," one five-star review said of a tour from Bangkok last January.

Another rave review of a tour in Nonthaburi praises an "incredibly fun and exciting" day spent "elephant riding, monkey feeding and visiting tiger temple, where we fed a 7 month old tiger cub".

Consistent five-star reviews mean a tour can get a TripAdvisor "Certificate of Excellence".

Elephants are highly sociable and form tight bonds among family groups

World Animal Protection, which has already persuaded more than 100 tour operators to commit to stopping selling or promoting elephant tours and shows, now has TripAdvisor in its sights.

It says most people just aren't aware of the cruelty involved in the attraction they're reviewing. It wants TripAdvisor to give more information on animal attractions, and to override ratings so no operation where animal welfare is in question can get a certificate of excellence.

TripAdvisor has said its reviews are not endorsements, that it doesn't promote any illegal animal operations and that it is up to national governments to to ensure businesses are operating legally.

A key source of income

Intrepid Travel believes it was the first tour operator to stop including elephant rides in its packages altogether.

It did so after commissioning extensive research from World Animal Protection in 2010 which found almost no operators met its welfare standards.

Co-founder Geoff Manchester said some clients still asked about elephants, but that once they explained their view, "99% will come around".

Places like Thailand's Elephant Nature Park say they offer an ethical way for tourists to come close to elephants

Tourists can have other options if they want to encounter elephants, at places like hospitals which treat injured animals and sanctuaries like the Elephant Nature Park in Thailand, which rescues animals or buys them from commercial operators and sets them free to roam its secluded valley outside Chiang Mai.

But a flat ban on making money from elephants - which have been used as working animals in Asia for centuries - isn't necessarily practical.

"If all elephant riding stops the mahouts who own the elephants wont have any income, and they won't have any way of supporting the elephants," says Mr Manchester.

The onus should be on governments to help operators diversify, he says, citing a scheme announced in Thailand under which the government would pay mahouts to take their elephants into the jungle to roam free instead of using them commercially.

But he says that while demand for elephant rides might be declining from Western tourists, he had noticed a rising enthusiasm for them from Asian tourists.

And the truth, he says, is that the rides "won't stop unless the demand stops".

- Published26 April 2016

- Published2 February 2016

- Published6 July 2014