How the lives of Osama Bin Laden's neighbours changed forever

- Published

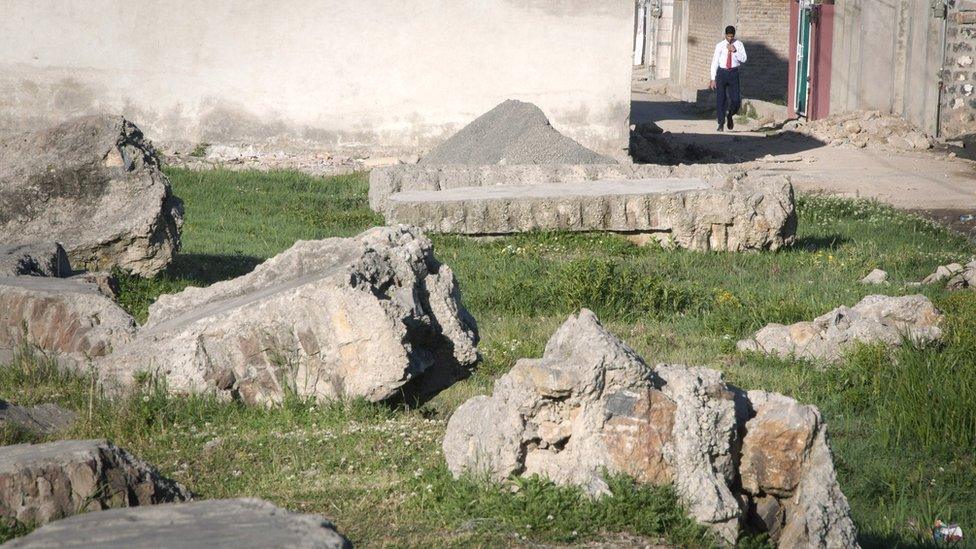

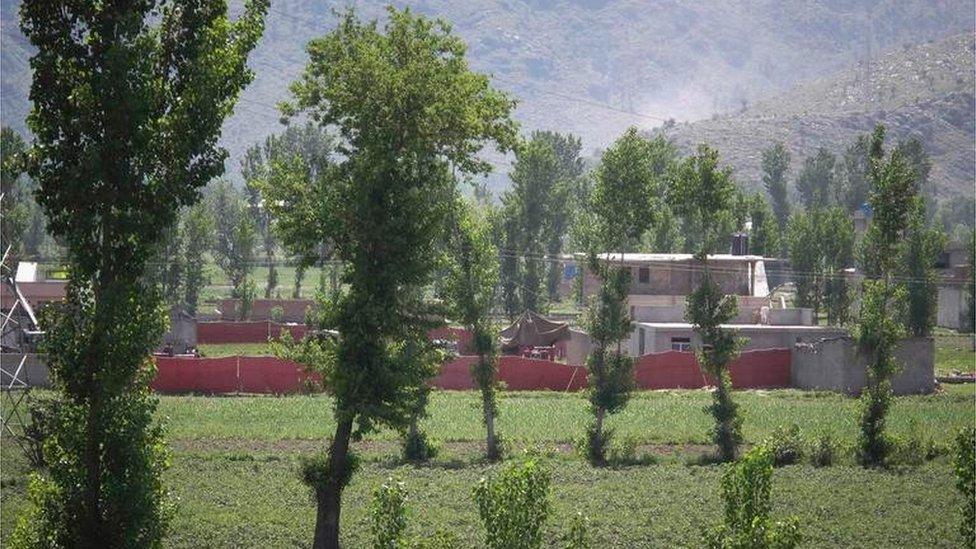

Bin Laden's compound in 2012, before it was completely demolished

Al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden was killed in Abbottabad, Pakistan in a dramatic and bloody raid by US Navy Seals on 2 May 2011. Five years on the BBC's M Ilyas Khan finds loose ends, unsettling and unanswered questions, and a neighbourhood changed forever.

It is a precarious life next to the razed Bin Laden home

The open spaces that once surrounded the sprawling compound are fast disappearing. When I first saw it, just hours after al-Qaeda's leader-in-hiding was killed, it was an open and quiet suburban lane.

Now new houses - small, box-shaped, concrete - have come up and it has the feel of an ill-planned and crowded neighbourhood. But the view opens up as you venture further down the street to where the tall walls of the compound once stood. That was all razed, just months after his killing.

The compound has now been completely razed

Fragments of the concrete beams from his home are strewn about. A small pipe jutting out of the ground continues to spout water, as if a natural spring even though it is actually connected to a deep well that once pumped drinking water to the Bin Laden household.

The water is now used by neighbours in an area where shallow well water is brackish and not everyone can afford deep drilling.

Bin Laden's drinking water is now used by his neighbours

This well is located in what was the Bin Laden compound

What is unchanged is the memory of the event - which rocked Abbottabad and the entire world in May 2011 - and the measures some still take to avoid discussing it.

A construction worker who worked on the compound agreed to see me when I assured him we wouldn't reveal his identity. But when I reached his home, there was a padlock on his door. A neighbour said he took his children out the previous night.

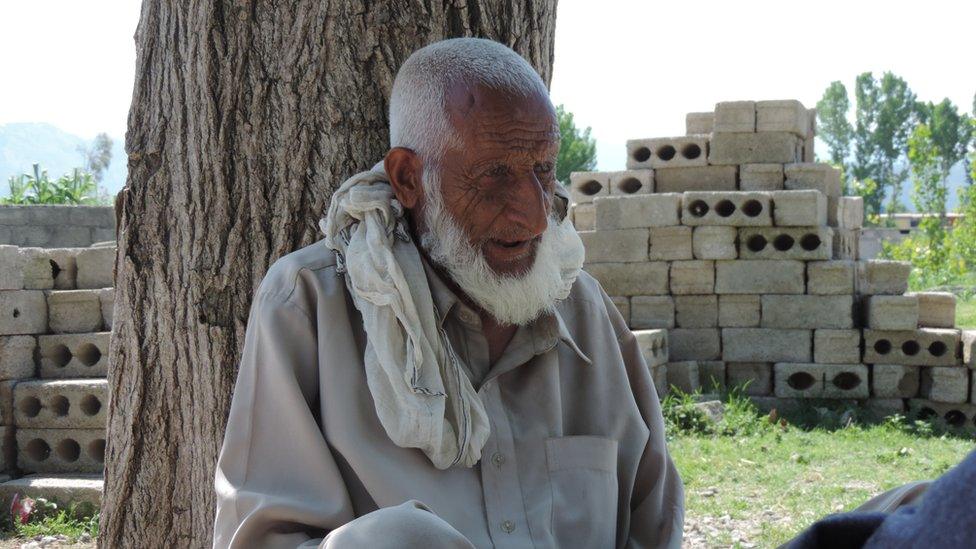

The old neighbour in and out of custody

One man will talk.

"They would tie our hands, blindfold us"

Zain Baba, 84, has the distinction of being the first, and closest neighbour of the Bin Ladens. His small house was across the street.

Every morning he comes out and sits under a huge maple tree, a sort of assembly point for the retired men of the neighbourhood.

Until that night, he and his son Shamrez Khan worked as night watchmen for Arshad Khan, an ethnic Pashtun who lived in the compound with his family and that of his brother.

To the Americans, Arshad Khan was the same man as Abu Ahmed al-Kuwati, the Kuwait-born courier of Bin Laden, whose phone calls apparently led them to the hideout.

Life goes on in Bin Laden's old neighbourhood

Zain Baba and his son had access to some parts of the compound. They were picked up by Pakistani intelligence after the raid and kept in custody for two months.

"They would tie our hands, blindfold us and take us for long drives from one place to another. They wanted to know if we saw Osama in the compound. We kept telling them that we didn't see anyone except the two brothers and some children."

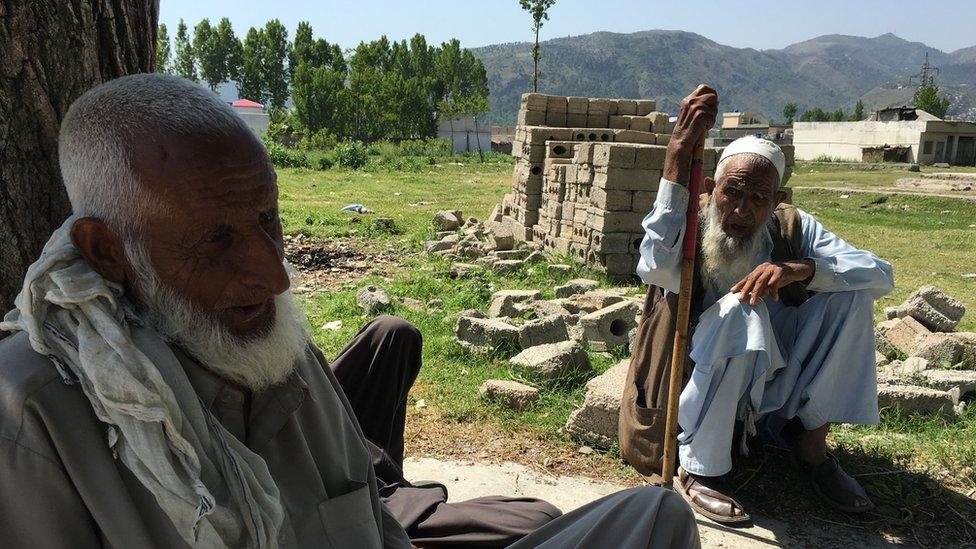

Zain Baba and his friends meet daily under a maple tree

Five years later, he is still on the security radar. When foreign journalists come to the area, they want to talk to him, he says. "Men in plain clothes riding government vehicles" drop by to ask questions about the visitors, and to warn him against "talking to such people".

He recounts how a French journalist who interviewed an aged neighbour of his was recently escorted away by security officials. The old man they had interviewed died later that night. The next day the men in plain clothes came to see Zain Baba and asked him about the whereabouts of his son, Shamrez.

"I am tired of people asking questions. I don't want to give any more interviews to the media. Even when the media speak to someone else, the security people come asking for me."

He has a wryness about him and a fatalistic approach, but ultimately no true fear. He believes little can happen to him now - it is a situation that tells more about the paranoia of the security agencies than his safety.

The contractor who was never the same again

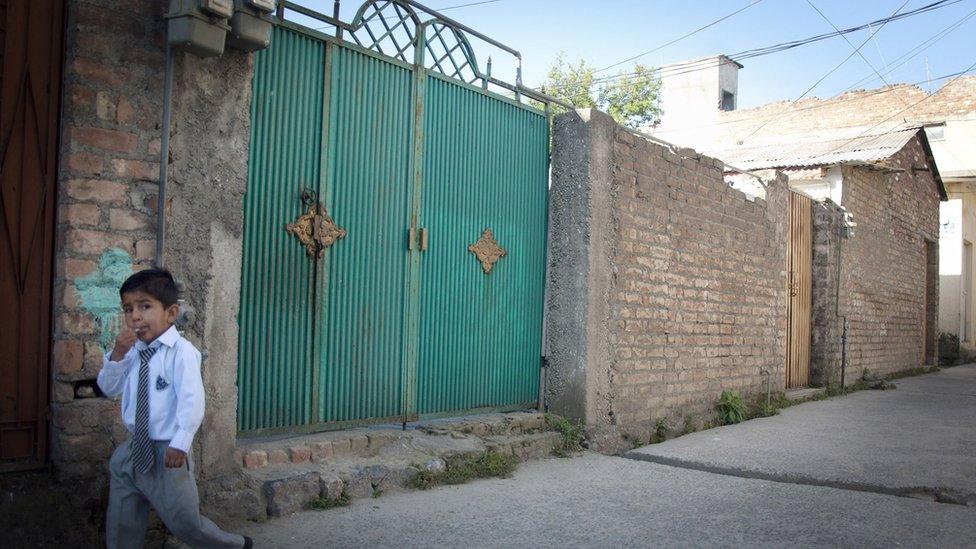

The gate to Shakil Rafiq's home was shut - and he was nowhere to be found

Shakil Rafiq is a changed man. He used to be an amiable and responsive man who mixed with his neighbours.

"He now walks with his head down, and if someone shouts a greeting at him, he just responds by waving a hand," says one neighbour.

A small-time construction contractor, Mr Rafiq's business picked up after he was employed by Arshad Khan to supply labour and material for the construction of the Bin Laden compound.

Mr Rafiq's life changed a few years later, after the US raid. Security agents raided his house and took him away. A neighbour who witnessed the arrest said the street was taken over by men in plain clothes and Mr Rafiq was escorted out carrying a shoulder bag.

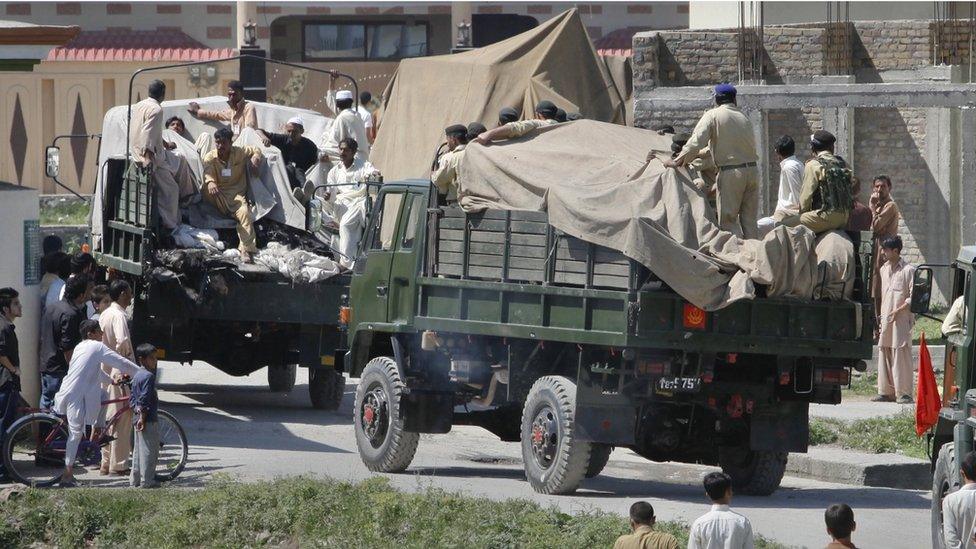

Soldiers cleared debris from Bin Laden's compound after the US raid in May 2011

A security official who was part of the post-raid investigations says Mr Rafiq was picked up after it was found that various facilities were registered in his name. He didn't return for several months.

In the intervening years, Mr Rafiq has disappeared several times for varying durations, the latest being just a few months ago, say neighbours and local journalists. He did not respond to several attempts by the BBC to contact him.

One neighbour said: "Every time he walks out carrying a shoulder bag, it's a sign that he is going to be away for a while. Where exactly? Nobody knows."

The policeman who knew too much?

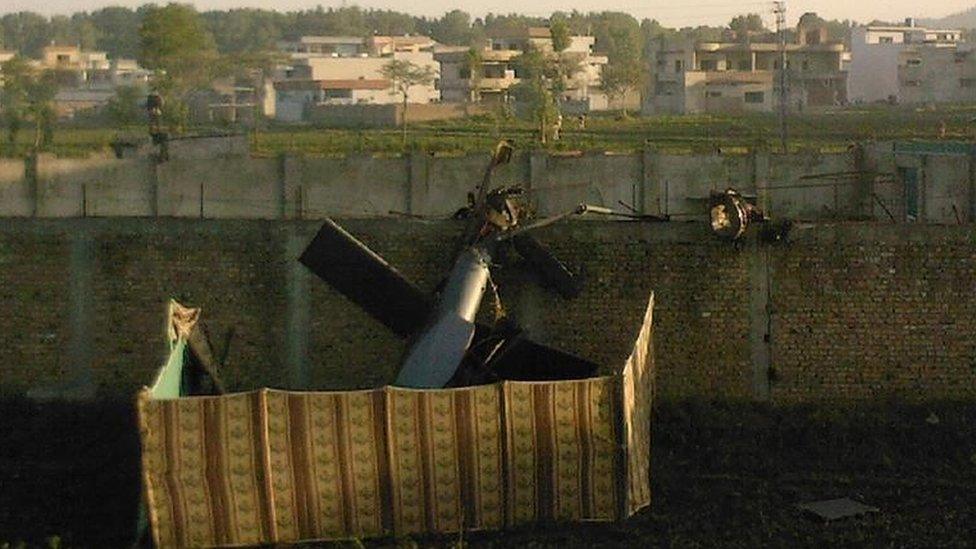

A US helicopter crashed near the compound during the US raid

Did policeman Yasir Khan know more than he ought to? Did he have direct links with residents of the compound? Nobody will know.

He was posted to Abbottabad's police intelligence department back in May 2011, and did not live far from the compound. He was often seen hanging around in the area in plain clothes, sniffing for information like all spies do, says one senior security source.

His colleagues say he was at home around midnight on 2 May, when the Americans destroyed one of the helicopters that crashed during the raid.

The sound of the blast alerted police, and Mr Khan was one of several officials called to respond. The next day he was picked up by men in plain clothes.

Dozens were taken away after the raid

He is among dozens of people taken away by men in plain clothes after the raid. He is the only one who has not yet returned. A security official says he was alive until a year ago, but did not say where he was being held, or by which intelligence service.

His family never speak to the media, but their pain is not hidden from their neighbours. His mother is still alive and he has a wife and children still clueless about his fate.

One of the first men on the scene

Unusual but not extraordinary. That was how police interpreted the midnight blast of 2 May 2011.

Abbottabad is a garrison town, and a helicopter crash, though rare, could be expected, explains a police officer who was among the first police officials who entered the compound.

The compound was closely guarded in the days following Bin Laden's death (file photo)

"In the dark, we couldn't make out if the burning helicopter was Pakistani or American." They found women and children crying and shouting.

The compound was soon taken over by the military and the police couldn't probe the matter any further. He remained part of the military-led investigations, but will not share those details.

"It was an embarrassing moment. We could neither admit nor deny that Osama was here. Our best option was to not to say anything."

But staying silent on the matter has not helped the ghost of Bin Laden leave the town.

"There is a continuing state of alert in Abbottabad," he says.

The legacy of the most wanted man on earth

Osama Bin Laden evaded capture for nearly a decade

The implications of that night resonated well beyond this neighbourhood. Would Bin Laden be turning in his grave over the way al-Qaeda has gone? Could he have changed things?

It has been increasingly overshadowed by the so-called Islamic State in many parts of Africa and the Middle East.

In the Afghanistan-Pakistan region - which is the original birthplace of militant Islam - al-Qaeda continues to have links with local groups but appears to be more of one-among-equals now. Many say that al-Qaeda is more decentralised, with regional groups acting independently of the central leadership.

This could be partly because the leaders are not as militarily experienced, ideologically articulate or charismatic as Bin Laden was, and hence cannot inspire the same loyalty. But it could also simply be the changed security environment.

The embarrassment may be the key to the paranoia

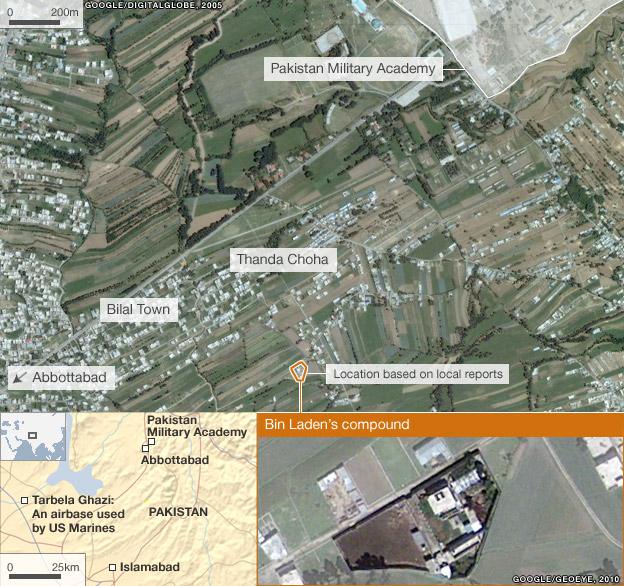

It was the fact that Bin Laden's home was spitting distance from a prime military academy that led to speculation about the lack of, or the extent of, Pakistani complicity.

It has been a huge embarrassment for the Pakistani military, which literally runs the country's security policy - and so the response of officials has been silence.

They have also kept tight vigil over those connected to the compound to prevent them from passing on any information to the media or "foreign agents disguised as journalists", as one official put it.

Pakistani and US officials have publicly said that Pakistani authorities were not aware of Bin Laden's presence in Abbottabad, but many have contrary views.

American journalist Seymour Hersch argues Bin Laden had been in Pakistani custody since 2006 and was killed after the country struck a deal with US. Part of his argument is the ability of US helicopters to fly nearly 200km over Pakistani territory to get Bin Laden, and fly back, without being interrupted.

A screenshot of a video seized from Bin Laden's compound, released by the US, shows a man identified as Bin Laden watching President Barack Obama on TV

If true, then this "prisoner" also had enough freedom to travel around in the tribal region until as late as May 2010, as the BBC discovered on good authority.

Official circles and independent analysts here say that while the Pakistani government could not possibly have had any knowledge of Bin Laden's whereabouts, that a handful of top officials in some powerful quarters may have known cannot be ruled out.

Either way, the events of a small block of this mountain town five years ago not only changed the lives of those unlucky enough to be his neighbours, but also marked a moment with massive implications for the world as we know it.