What's the point of Asean?

- Published

Judge Asean by what it has prevented, rather than achieved, some say

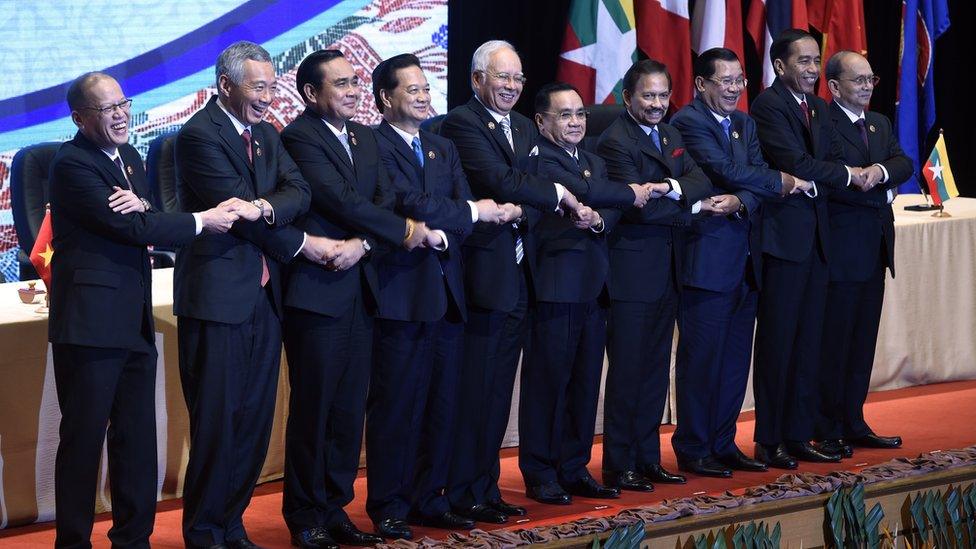

Fourteen years after they first began discussing their differences with China over the South China Sea, the 10 members of Asean - the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, external - have once again bowed to pressure and produced a watered-down joint statement at their summit, in Laos.

No mention of China, which has been creating "facts" in the sea by building islands on disputed reefs.

No mention of the recent ruling at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague that China had no historic rights over the area.

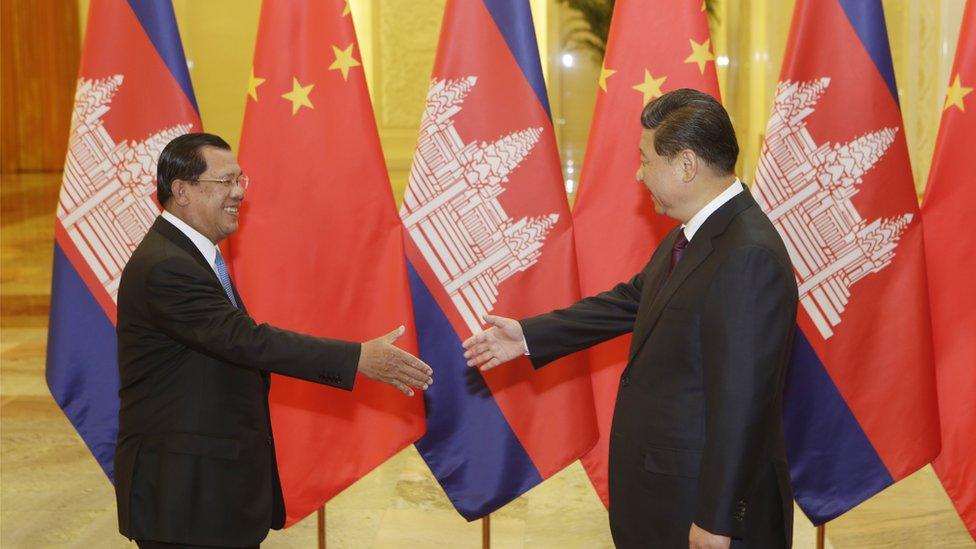

Once again, it was the smaller Asean members under China's thumb - Cambodia, and host-nation Laos - that were the weak link in the bloc's efforts to stand up to its giant neighbour.

Asean avoids criticising China over sea

And so, once again, the question pops up: what is the point of an Asean so crippled by its consensus-based decision-making that it rarely makes any decisions at all?

Cambodia has backed China in regional meetings, and been lavished with aid

Many years ago I put this question to Singapore's then-trade minister George Yeo. He suggested I look not so much at what Asean had achieved, as what it had prevented. An impoverished, war-torn region caught up in the hottest of Cold War conflicts was, he said, turned into a zone of peace and prosperity.

By diffusing disputes through the "Asean Way" of meetings, seeking consensus and forswearing any interference in one another's internal affairs, the economies of South East Asia were able to tap into the global supply chain and start their impressive growth.

When Asean was founded, the region was embroiled in Cold War conflicts

What is Asean?

Founded in 1967 by Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines

Later expanded to include Brunei, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar

Purpose is to promote co-operation and collaboration between member states, peace and stability, economic integration and growth, and an "Asean Community"

Works on principles of consultation and consensus, non-interference, non-confrontation and the peaceful settlement of disputes

Asean Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia

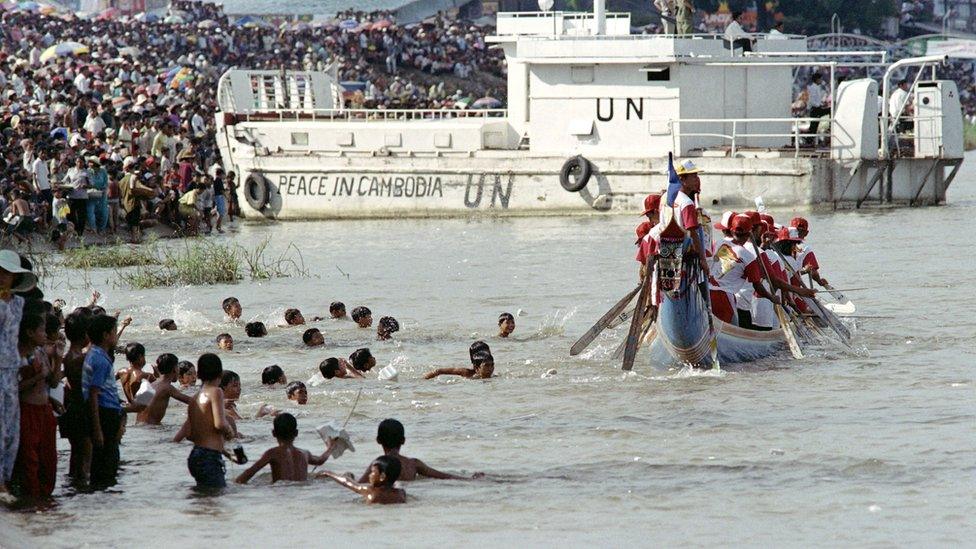

Asean's proudest achievements are its role in ending the Cambodian civil war and bringing the three Indochinese countries into its fold in the 1990s, and its patience, in the face of Western criticism, with Myanmar's military leaders as they shuffled in the direction of democratic reform.

But the association's weaknesses have been cruelly exposed by China. There is no mechanism to ensure solidarity in Asean, just a seemingly endless series of meetings - more than 1,000 every year - in which backroom diplomacy can undo a hard-won consensus decision in minutes.

Asean diplomacy in the late 1980s helped bring an end to the Cambodian conflict

The South East Asian region saw rapid economic growth in the decades after Asean was formed

The Asean secretariat, with just over 300 staff, is hopelessly under-resourced just to manage the logistics of these constant get-togethers.

There are no Asean institutions to rival the EU's Commission. Council of Ministers and Court of Justice. The so-called Asean Economic Community, launched with great fanfare in Malaysia last year, is little more than a set of distant aspirations.

Asean also lacks leaders of the stature of its founding fathers to drive the bloc forward.

Indonesia, traditionally the weightiest power in the bloc, no longer wields the kind of clout its long-standing former foreign minister Ali Alatas did in the 1980s and 1990s.

There is no-one now to match the charisma of Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew and Malaysia's Mahathir Mohamad.

Its supporters often cite Asean's usefulness as a forum that brings regional powers together, like the East Asia Summit, and the Asean Regional Forum which are attended by leaders and foreign ministers of countries as diverse as the US, Russia, India, China, Japan, Australia and North Korea.

Asean states no longer have charismatic leaders to push it forward - like former Malaysian PM Mahathir Mohamad

...or his late Singaporean counterpart Lee Kuan Yew

It is true there is nothing else quite like these gatherings and, although they invariably produce bland and non-committal joint statements, they do offer unique opportunities for otherwise impossible bilateral meetings.

I recall the excitement in Brunei in 2002 when, in the aftermath of President George W Bush's "Axis of Evil" speech, we heard that Secretary of State Colin Powell had met his North Korean counterpart over a cup of coffee. It turned out, though, that with the complications of translation, they never went much beyond some innocuous pleasantries.

But the truth of these big meetings is they end up eclipsing Asean itself. It's a bit like holding a party, inviting a group of super-celebrities, and then finding that the stars only talk among themselves.

In a region confronted by growing tension among the powers on its borders, and challenges like climate change, it is no longer enough for Asean to be the mere talking shop it has been content to be for so long.

- Published25 July 2016

- Published20 April 2015

- Published22 November 2015