China censorship: How a moderate magazine was targeted

- Published

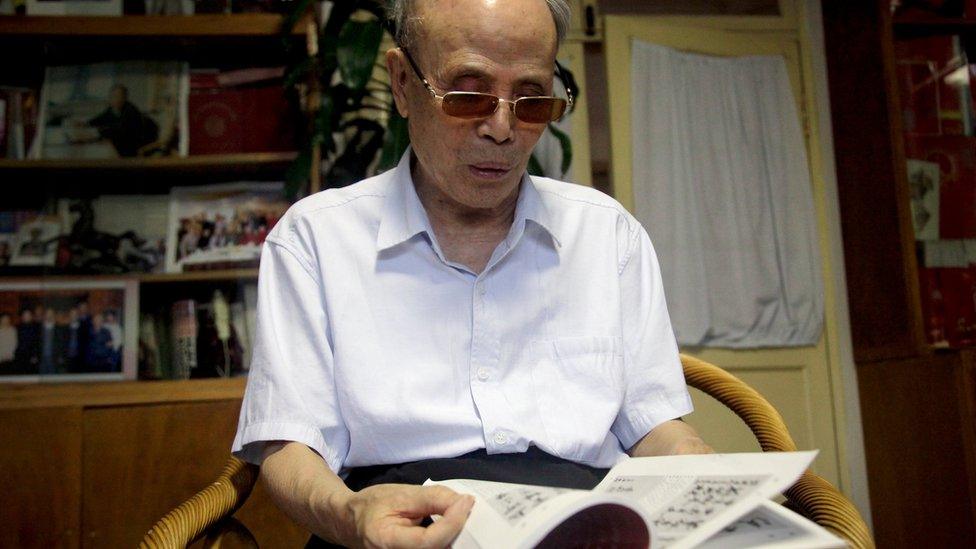

Founder and director Du Daozheng speaks to the BBC's John Sudworth

"China gets tough on media freedom" isn't much of a shock headline these days.

But events at Yanhuang Chunqiu - a distinguished, if somewhat dry, history magazine - are evidence of a watershed moment, its former staff believe.

"I've not seen this kind of thing since the Cultural Revolution," the recently dismissed - some might say purged - founder and director Du Daozheng tells me.

In July, the magazine's offices were taken over by strangers, who changed the computer passwords, began to open the mail as if it was their own and took over the running of the magazine.

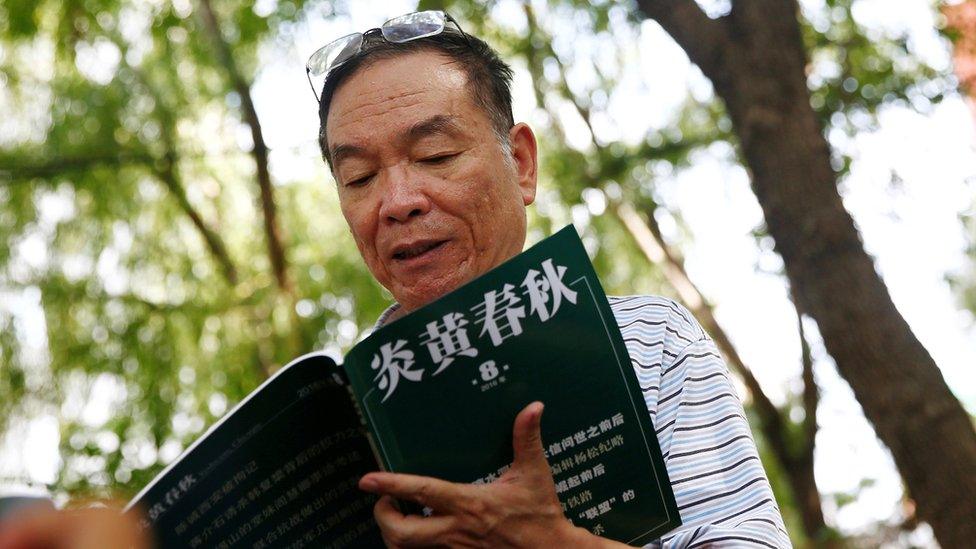

The magazine has long offered a mild critique of the official Communist version of China's history

"It was a co-ordinated effort to block us and to contain and control us," Mr Du says.

At 93 years old, he does not look like your usual target of Chinese government oppression.

Granted, his magazine - whose title loosely translates as China Through the Ages - has long been offering a mild critique of the official Communist version of history.

But it is hardly a radical voice of opposition. Mr Du himself has been a card-carrying member of the Party for almost eight decades and was, for a long time, a senior editor at Xinhua, the state-run news agency.

'Within the system'

"All other newspapers only speak with the same voice," he says.

"We offered something different, but we were still a force within the system, using our voice to advocate moderate reform."

Mr Du has been a member of the Communist Party for eight decades and was formerly an editor at the state-run Xinhua news agency

There have been attempts to clip the magazine's wings in the past.

In 2008 it broke a longstanding taboo by publishing a series of articles about Zhao Ziyang, the former party leader ousted in 1989 who spent the rest of his days under house arrest.

And one of the magazine's senior editors, Hu Dehua, is himself the son of another reform-minded former leader, Hu Yaobang.

History questioned

But the magazine has managed to stay in business, partly because of the backing of influential sympathisers. In recent years it boasted a readership of some 200,000 a month.

Another series of articles, published in 2013, ruffled feathers by questioning the details of a well-known story about Communist soldiers fighting against the Japanese in World War Two.

The heroic tale has the five Chinese soldiers jumping off a cliff so they would not be captured alive, but the article expressed doubts about key aspects, including how many Japanese soldiers were supposed to have been killed in the preceding battle.

"There have been many times when they want to say that we cannot have a different opinion," Mr Du tells me.

"But this time it's serious. They really do want to shut us down."

So, he says, in the face of the appointment of new editorial staff by the authorities, the original staff had no choice but to issue a notice announcing that any future editions of the magazine would have nothing to do with them.

But they are not giving up.

This week they went to court to try to challenge what they see as an illegal attempt to stifle their voice, although few observers would give them much chance of success.

New pressure

The plight of Yanhuang Chunqiu is seen as symbolic of the tightening of control over freedom of expression under President Xi Jinping.

Lawyers, activists and religious groups are all feeling the pressure as his government moves against what it sees as the dangers of pluralist, Western ideals.

But that a history magazine should be in the firing line has shocked many observers.

The past has always been a sensitive subject in China but Yanhuang Chunqiu was at least one place where China's often dark and difficult history could be openly discussed as a way of illuminating the future.

Even that opportunity has now gone.

"I had high expectations for Xi Jinping," Mr Du says.

"But in general I think he is going backwards. The consequences of this clampdown is not only about our magazine but it will harm the party and the country."

- Published29 March 2016

- Published23 February 2016

- Published22 August 2023