Nepal to investigate civil war crimes

- Published

A memorial marks the spot where 38 people died in the June 2005 Maoist bomb attack on a passenger bus carrying civilians and soldiers

The two commissions set up to investigate crimes committed during Nepal's civil war have received nearly 57,000 submissions, but many victims are sceptical about getting justice. The United Nations has already said it will not support the process as it does not meet international standards so what hope is there for reconciliation? BBC Nepal's Phanindra Dahal investigates.

It had been a joyful occasion. Nawaprasad Ghimire had just celebrated the wedding of his youngest son in June 2005.

Six members of his family were on a bus returning home, passing through Madi Chitwan, a town nearly 200km south-west of the capital Kathmandu.

Royal Nepal Army soldiers in civilian uniforms were also on the bus.

But Maoist rebels had planted a roadside bomb and detonated it.

Nawaprasad's daughter Ganga Devi Lamsal, her husband Dinesh Lamsal and granddaughters Dipika and Dikshya Lamsal in happier times

Thirty-eight people died, including Nawaprasad's son, daughter, son-in-law, sister-in-law and two granddaughters.

For more than a decade, from 1995 to 2006, Maoist rebels seeking to establish a people's republic fought the army commanded by the king in the Himalayan nation.

Now 74 years old, Nawaprasad was unable to stay in his village because the memories were too painful.

Justice delayed, justice denied?

Last month, he submitted a complaint at the Truth and Reconciliation commission (TRC), demanding that local Maoist cadres and their top leaders be held accountable for the attack.

"Just because a few military men were travelling in it, a deadly attack on a civilian bus cannot be justified," he said. "They should be punished on the basis of international law."

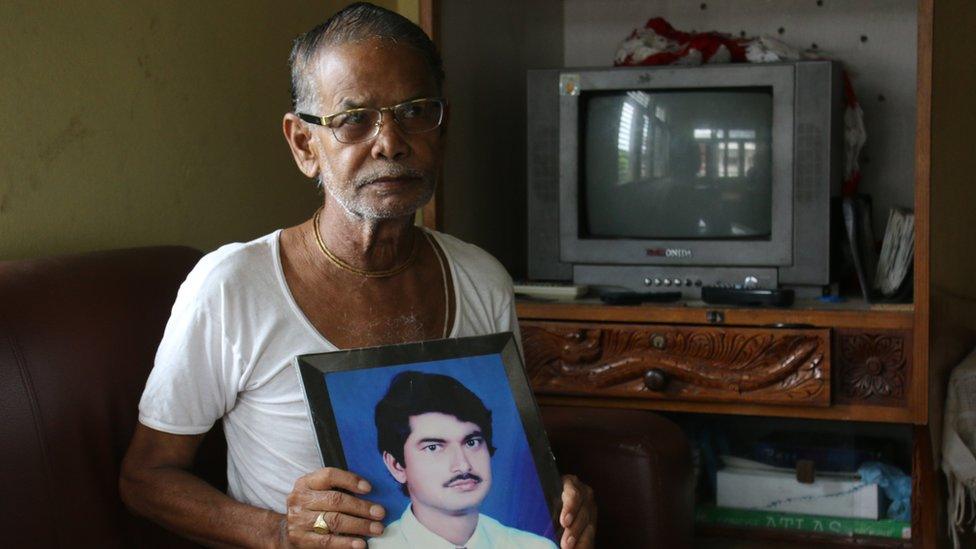

Nawaprasad holds a photo of his son Bishnu who died in the Madi Chitwan bus bomb attack

He listed former Maoist rebel leader and the newly-elected Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal in his complaint.

The conflict claimed nearly 16,000 lives and more than 1,300 people "disappeared".

A truth and reconciliation commission was part of the 2006 peace deal which also saw Nepal become a federal republic.

Nepal's new prime minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal (left), also known as Prachanda, was the leader of the Maoist rebels during the civil war. This is his second time running the country.

But the two commissions to investigate human rights abuses and the disappeared were only established in 2015, a sign of the political instability and poor governance that continue to plague the country.

Sangita Yonjan lost her father during a controversial military raid by the Royal Nepal Army while there was a ceasefire in August 2003.

She was a sixth grader when her father Baburam, a local Maoist in charge, and 18 others were allegedly killed by the military after being captured in Doramba village in Ramechhap district in central Nepal.

"My father was killed despite a ceasefire so his death is a heinous crime and those involved in it should face action," she said.

Sangita Yonjan is studying to be a nurse and hopes the new prime minister will get justice for her father

"The Maoists are back in the government and I hope their leaders will work seriously to provide justice to conflict victims like us."

The Nepal Army held one of its majors responsible for the Doramba killing and sacked him immediately after the incident.

But Doramba victims say no real progress has been made. They have filed a complaint against the then prime minister, home minister, the military commanders and former King Gyanendra at the TRC.

International concerns

The United Nations was involved in Nepal's peace process from the very beginning, but says it cannot work with the transitional justice mechanisms.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR) says provisions in the transitional justice act breach international human rights law and give power to the commissions to recommend amnesties in cases of gross human rights violations.

In February 2015, the Supreme Court of Nepal delivered a ruling scrapping the commission's power to grant amnesties but the law has not yet been amended.

D. Christopher Decker, project manager of the Transitional Justice Project of the United Nations Development Programme in Nepal, says the UN will not be able to provide support until the government takes step to ensure that the laws comply with international legal obligations.

"In any peace process or in any settlement, the UN cannot support any mechanism which can provide an amnesty for gross human rights violations or serious violations of humanitarian laws," he said.

He warned that the conflict-era abuses could haunt Nepali stakeholders for a long time if the transitional justice process fails to garner international support.

Officials at the TRC say they are deprived of the expertise and resources to investigate the abuses in the absence of the UN support.

They have asked the new government to immediately amend the transitional justice act and to introduce laws criminalising torture and disappearances to facilitate their investigation.

Political wrangling

Human rights activists say there is a lack of political will to address these issues.

Mandira Sharma, president of the Advocacy Forum Nepal, says there has never been a serious discussion on how to best address the past.

She also says political parties and the security apparatus have never wanted the TRC to succeed.

"There were some attempts by different actors including the Supreme Court, to rescue the transitional justice process but politicians have been making all those efforts fail as well."

They have not respected the Supreme Court's decision which could have saved the legitimacy of the TRC," she said.

The new Nepali prime minister (in the middle with red scarf) marks the 13th anniversary of the Doramba killings where 19 Maoists were allegedly captured and killed by the army

The new ruling coalition led by Prachanda comprises the Maoists and the Nepali Congress, the two parties who fought against one another during most of the time of the conflict.

Both leaders have said they would accord high priority to address the stumbling blocks of the transitional justice.

The two commissions have six months to complete their investigations into the complaints though the law says the deadline can be extended for another year.

But the many victims of Nepal's conflict are doubtful, despite taking part in the process.

"I am not hopeful that perpetrators of this crime would be punished in Nepal," said Nawaprasad Ghimire.

"But even if they are not held accountable here, they should not get immunity."