The reverse exodus of Pakistan's Afghan refugees

- Published

Families returning to Afghanistan face an uncertain future

Pakistan's request for all three million Afghan refugees within its borders to leave is causing chaos on its borders and plunging families into uncertainty. Many Afghans have spent all their lives in Pakistan. The BBC's M Ilyas Khan reports from Peshawar.

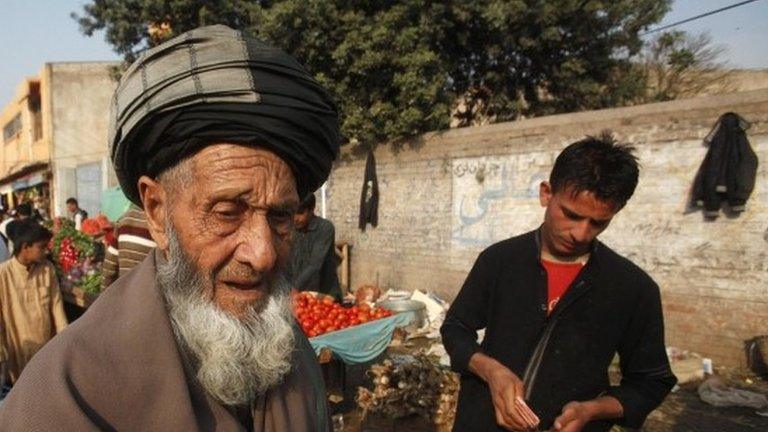

Noor Mohammad has been queuing for three days to return to Afghanistan - despite being certain that hardships face him on his return.

He fled to Pakistan in the winter of 1979, days after the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan and helicopter gunships started hovering over his village in Baghlan.

He was 12 or 13, and remembers the gruelling journey he made with his family.

Noor, right, with a truck carrying his worldly belongings

"We climbed the hills and started to move south. We went on for days, sometimes walking, sometimes taking a ride on lorries or ponies."

Thirty-seven years later, he has to move again, because his second home says he has overstayed his welcome.

His return journey will be less physically demanding than the one he made as a teenager - but not much easier.

When I met him last week, Noor and his family had spent three days stuck behind a 3km (two-mile) queue of lorries trying to reach the UN-run repatriation centre in Peshawar. And they still seemed to be days away from the centre.

They were angry and frustrated. Others in the queue said they had been waiting for nearly a week.

There were more than 200 lorries stuck on the road to the repatriation centre

I counted more than 200 lorries queuing up on the road near the repatriation centre, loaded with household goods, timber and firewood - the belongings of roughly 400 families, or around 3,000 individuals

The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and Pakistani authorities have admitted they were not prepared for the rush of refugees returning, and could not handle the influx.

Those waiting had to find what shelter they could from the sun

Families could be seen scattered along the highway in the August heat as they waited

Many made Pakistan their homes and fear Afghanistan is still years away from bringing health, education, business and livelihood at par with what they had in Pakistan.

So why are they returning?

The answer lies in the evolution of Pakistan's refugee policy.

Back in the late 1970s, the country welcomed Afghan refugees with open arms.

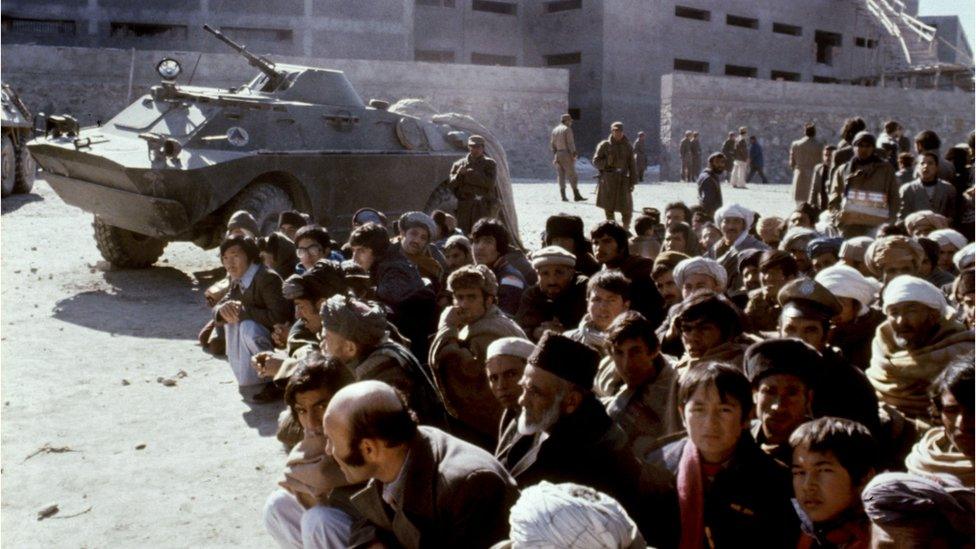

Unlike Iran, which confined refugees to camps and prevented them from indulging in politics, Pakistan allowed them to mix with local populations, and encouraged them to link up with Islamist camps that fed resistance to Kabul's communists.

The refugees were predominantly ethnic Pashtuns and merged well with Pakistan's Pashtun population. And they could be influenced to agree with Pakistan's emphasis on Islamic identity rather than Afghan nationhood as the basis of their resistance.

The Soviet Army invaded Afghanistan in 1979, propping up a communist government

As a result, many believe Pakistan welcomed the refugees in order to expand its influence in Afghanistan, which had traditionally tilted towards India, and to neutralise its own Pashtun nationalists who had been pushing for greater autonomy, sometimes bordering on secession, as some in the Pakistani establishment suspected.

But suspicions struck the Pakistani mind post-9/11, when an anti-Pakistan version of the Taliban began to evolve, with links to these sanctuaries.

Since then, the narrative of the Pakistani establishment has gradually turned against the refugees.

Yet despite the growing hostility, Pakistan was initially in no hurry to send the Afghans home.

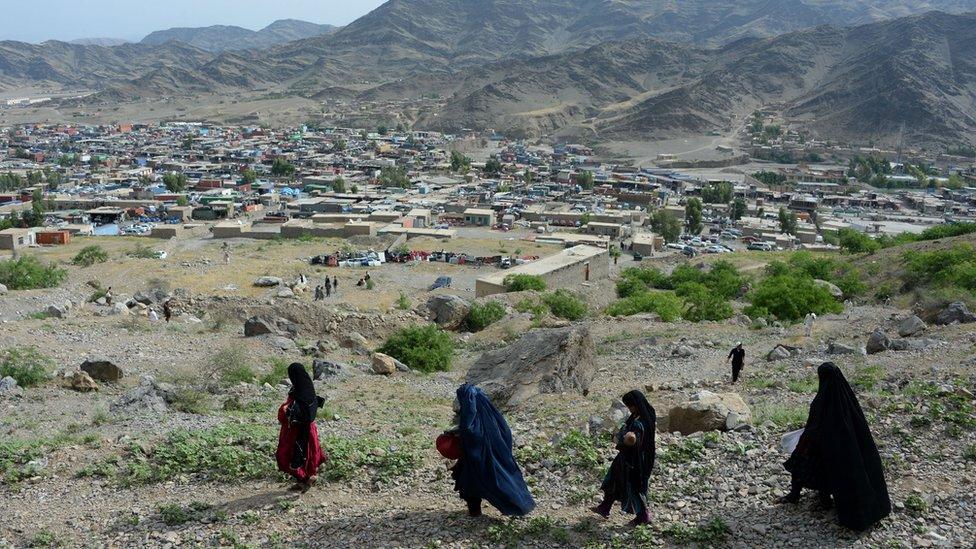

Pakistan has now set a deadline for the Afghan refugees to leave

A UNHCR-funded repatriation programme for refugees was initiated in 2002, but Pakistani and UN officials say take-up was slow.

Pakistan issued various deadlines for the refugees to leave, but they were often long-term and not enforced, because the UNHCR wanted any repatriation to be voluntary.

The decisive push came in December 2015, when Pakistan suddenly set a six-month deadline for the refugees to leave.

It extended the date for another six months in June, but at the same time closed the main Afghan-Pakistan border crossing in Torkham, and put a ban on Afghans crossing over without travel documents.

People were forced to pass through mountains to enter Pakistan when the Torkham border was closed

It was this ban that showed Pakistan meant business this time - and convinced Noor Mohammad to leave.

"Some of our family members who had gone to Kabul for summer were stranded there," he says.

"We don't have the money to pay passport fees for all our family, which numbers over 40. So we thought it was time to go."

Also in June, the UNHCR doubled its repatriation package from $200 to $400 per head for returning refugees, providing added incentive to poorer families that had not sunk deeper roots in Pakistan.

'Afghano-phobia'

The future is now uncertain for many Afghan refugees.

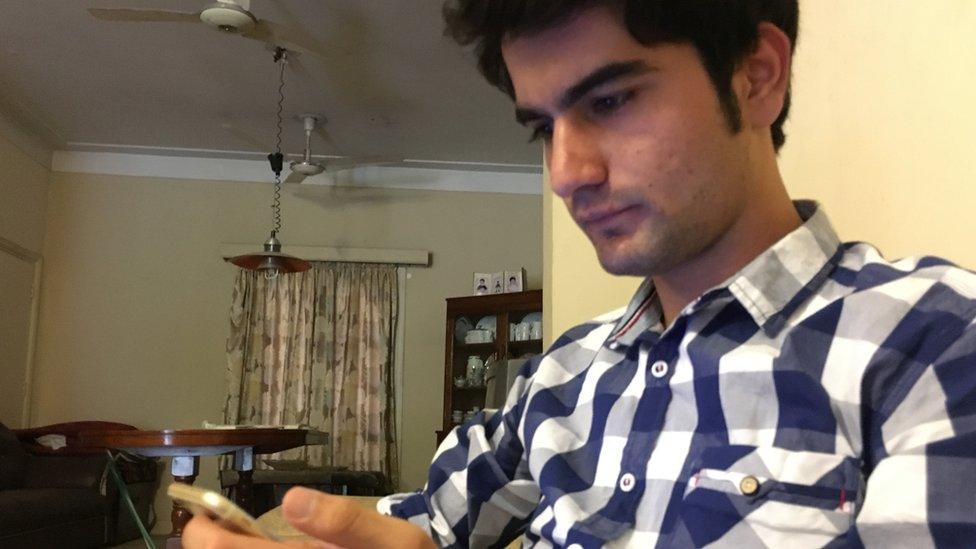

Khalid Amiri, a 21-year-old student, has lived in Pakistan since he was a few months old.

He is now studying a Master's programme at Peshawar University, which does not finish until the end of 2017.

Khalid says there has been a social media campaign against Afghan refugees

He and around 9,000 other Afghan students in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are not sure if they will be allowed to complete their courses.

Khalid believes the moves to force refugees out are due to "growing Afghano-phobia in Pakistan".

He says there has been "increased harassment of refugees by Pakistani police", and "a hate campaign against the refugees in the Pakistani media since the [December 2014 attack on Peshawar's] Army Public School".

The hate has spread to social media in recent months, with "hashtags like #KickOutAfghans and #AfghanRefugeesThreat", he says.

The prospects for Afghan businessmen are even dimmer.

Mohammad Ismail's father left behind his antiques business in Ghazni and migrated to Peshawar in 1983. Here they made a fresh start and established themselves as certified exporters of antiques and rugs to Europe and the Far East.

Mohammad Ismail, left, is worried he'll lose money selling his inventory

But in June, Mohammad's children who were on vacation in Kabul were stranded there when the Torkham border was closed down. They have since obtained Afghan passports and visas for Pakistan, which means they have lost refugee status.

He now has to start from scratch, like his father did 33 years ago.

"My biggest problem is to get rid of my inventory. No one will give me a fair price because they know we are desperate. There's also money stuck up in credit lines. It will take time."

Baryalai Miankhel, a leader of Afghan refugees, says he expects the UNHCR, and the Pakistani and Afghan governments, to develop a phased programme of repatriation, spread over three to four years, "to soften the blow both for the refugees and their client populations in Pakistan".

There are indications that he may be right, but many refugees remain anxious.

Thousands of Afghan traders run stalls at Board Bazar, the largest refugee market in Pakistan

And those who await the returning refugees in Afghanistan will not be patriots holding flowers in their hands but predatory businessmen, transporters and property owners eager to fleece them of whatever little they have.

Noor Mohammad knows this.

"House rents in Afghan cities have spiralled to $300 and $400 a month, and our houses in the villages are in ruins," he says.

He says his only option, once he returns to Afghanistan, will be to build a shelter "as quickly as possible", given that "winter is coming".

In what some would call a cruel twist of fate, Noor's family will have to stay in a tent until he builds a shelter. It reminds him of the UN tents he lived in 37 years ago, when he first arrived in Pakistan as a refugee.

"For us, it's back to the tents," he says.

- Published2 June 2016

- Published5 May 2015

- Published26 February 2015