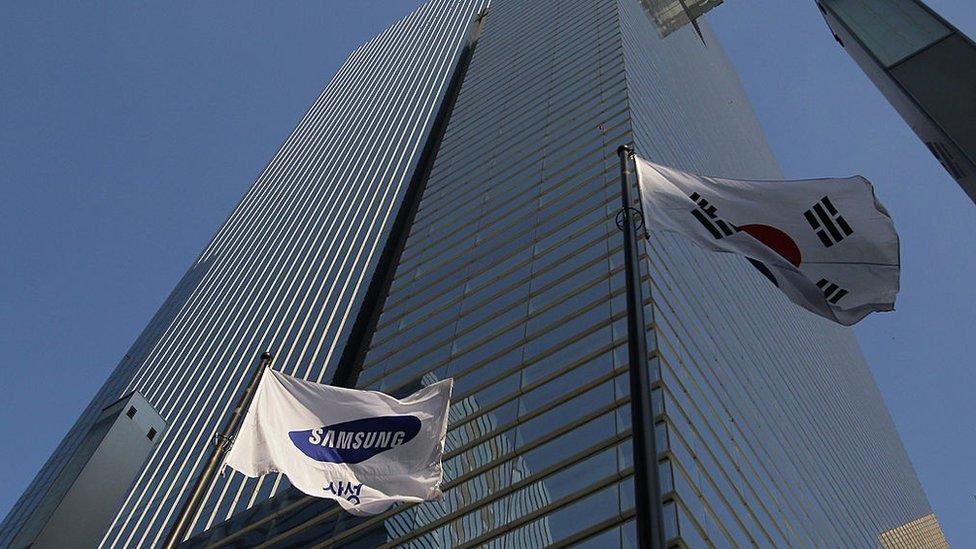

Chaebols: South Korea's corporate fiefdoms

- Published

As Samsung burns through money faster than a flaming phone, the one person you won't see fronting up before the cameras is the patriarch of the company.

Lee Kun-hee, Samsung's chairman, is a very sick man.

He had a heart attack two years ago and has not moved far from his hospital bed since then, if he's left it at all.

Samsung says little about his condition but nobody expects him to return to his office.

Nor has his son, Jay Y Lee, said anything in public.

The diffident Mr Lee has inherited the family firm but is yet to indicate how he proposes to run it.

Contrast this with the hoopla of Apple.

Whereas the show-man and genius, Steve Jobs, became the face of the company, doing all the razzmatazz in the product launches, Samsung's way is to let the product do the talking.

Which is fine except when the product catches fire.

The company is sometimes called the Republic of Samsung because this great, sprawling family firm has the economic clout of many countries.

You can be born in a Samsung hospital and end your days in a Samsung funeral parlour.

In between, you might live in a Samsung flat, with everything insured through Samsung Fire and Marine Insurance.

Samsung chairman Lee Kun-hee (r) had a heart attack two years ago

You might go to Samsung's amusement park, South Korea's largest.

This resort - Everland - is actually more significant than it seems.

It's very hard to get to the bottom of Samsung's finances because the 70 or so subsidiaries are all so intertwined.

But Everland is key.

The ailing patriarch Mr Lee and his son and two daughters own a controlling stake in the resort - and the resort controls the rest of the company.

This lack of clarity is typical of chaebols. They sprawl.

Hyundai makes cars, for example, but also has department stores.

Lotte runs department stores but also manufactures chemicals.

The word chaebol is a combination of the Korean words for clan and wealth.

Put the two together and it's a recipe for dispute.

Clans fall out and often when the patriarch dies the sons, and occasionally daughters, end up fighting in court over who gets what.

Dirty washing gets aired.

Hanjin Shipping became insolvent in August

And it does so quite spectacularly when chaebol chiefs break the law.

The 55-year-old chairman of Hanwha, for example, South Korea's tenth-biggest company, once took it upon himself to get a bunch of heavies to kidnap and beat up youths he believed had set about his son in a bar.

Or think of Hanjin Shipping, currently trying to fend off bankruptcy.

In June, its former chairwoman was accused by prosecutors of selling shares in her own company the day before their price crashed when bad news was published.

Hanjin owns Korean Air and you remember that the daughter of the chairman received a suspended sentence, after initially being jailed, for turning on cabin staff on one of daddy's airplanes because they didn't serve nuts to her satisfaction.

Samsung's own brush with the law came in 2008 when the chairman - the ailing Mr Lee - was fined and given a suspended jail sentence because of a Samsung slush fund used to bribe politicians and prosecutors.

He was pardoned by the president a few months later.

Cho Hyun-Ah was involved in an air rage incident concerning macadamia nuts

Fifty years ago, the general air of corruption at the top of South Korea's conglomerates prompted the country's modernisation.

The country's military strongman, Park Chung-hee, made a decision: the poor land he ruled with an iron fist would become modern.

He told the chaebol leaders that they were corrupt, and he was going to put them in jail and take away their corrupt earnings.

There was only one way they could escape that fate.

They would have to create the industries of a modern economy: shipbuilding, automobiles, electronics, steel making.

And so today's modern, prosperous economy was born, virtually on command.

Fifty years on, South Korea is still very hierarchical, though democratic.

The corporate patriarchs rule their fiefdoms, perhaps even from the sick bed.

But can that authoritarian style still work when agility is the necessary quality, to adapt and create and innovate?

And to make phones that don't catch fire?

- Published13 October 2016

- Published11 October 2016

- Published12 February 2015