Going out in Kabul: Little joys in the shadow of fear

- Published

Kebabs prepared at a restaurant in Kabul, a city where the security situation makes it harder, but not impossible, to go out and relax

Going out in Kabul is not straightforward. Restaurants and hotels are often targeted by militants, and many employ heavy security. BBC Afghan's Haseeb Ammar has been out to see where and how residents and visitors can relax in the Afghan capital.

On a recent visit to Kabul, a friend and fellow journalist took me out for the evening.

"I would love to take you to a better restaurant with even more delicious food," he said. "But the security at the entrance is very strict. I don't feel comfortable there and I don't think you would either."

His words made me curious. In what kind of restaurants do Kabulis and foreigners feel comfortable letting their hair down? Is it possible to relax and have a good time when you're permanently worried about your safety?

Coffee with Kalashnikovs

One evening we visited a cafe popular with liberal-minded young women and men.

Unlike the more traditional places, here men and women were not separated and there was no sign of security guards or the concrete blast walls that are ubiquitous in Kabul.

For most Kabulis "eating out" means a snack at one of the capital's kebab restaurants

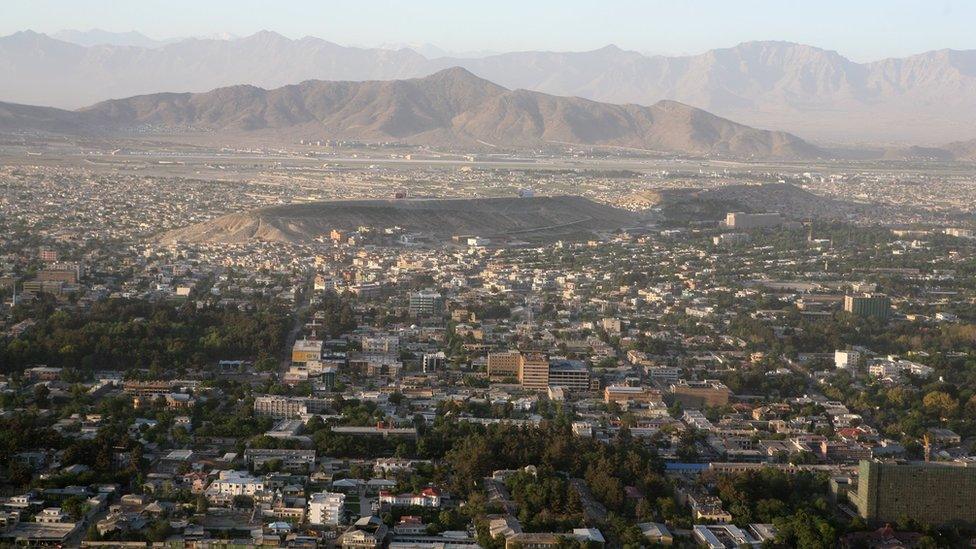

Kabul is Afghanistan's cultural and economic centre

Inside I found a friendly atmosphere with customers enjoying a mix of Afghan, Arab and American dishes, mostly hot fast food and green tea.

While we were munching sandwiches the tranquility of this little place was shattered by a quarrel between a gunman and the owner.

Everyone had their eyes fixed on the scene at the door. The owner was asking the man to leave his gun in his car, but the guest refused.

After arguing for 10 minutes, the two men reached a compromise. The gunman left the magazine behind but kept his gun at the table.

Challenging stereotypes

My curiosity grew further when, at nightfall, three women in their 20s walked in.

They were wearing light black and blue chadors that covered part of their heads. None appeared to be too concerned about their safety, although no-one wanted to be identified in this article.

After I introduced myself I found out that they were university students and quite willing to talk. I asked if they were worried to be in a cafe unaccompanied by a male relative at this time of the night.

"Today we wanted to challenge the stereotypical view that Afghan men have of women," one of them told me.

"We visited places where women rarely go, including a park which is normally packed with men.

"A lot of men surrounded us and started staring at us in a weird way, but we just ignored them. We wanted to show that we have the right to enjoy our time and have the same freedom as young men have."

Traditional restaurants are frequented mainly by men

I asked them what kind of freedoms they wanted most in Afghanistan's conservative society.

The answer: "We don't want men who see us like this in a cafe to be curious. No man should be interested in coming to ask us whether we are worried or not to come to such places."

Not on the menu

On another day I visited a restaurant run by foreigners.

Concrete blast walls had been installed across the street and to get inside one had to pass security checks manned by armed guards at the gate.

It was not very different from the security you would find outside a ministry building or offices of an international organisation.

Armed guards are the norm at all international institutions or offices, including Kabul's American University, which came under attack in August

The low ceilings felt suffocating, but my companion promised that we were in one of the "best places in Kabul to have a good time and leave what bothers you behind".

All the waiters were foreigners serving Western food.

"What would you like to drink?" the waitress asked. "We have juice, beer, wine and whisky".

I smiled, and remarked that those items were not mentioned on the menu. The waitress smiled back without saying a word.

The restaurant is frequented by wealthy Afghans, some of whom live abroad or do business with foreign investors. I heard a mix of Farsi and English when I tried to listen to the general chatter.

"Some of the customers here are powerful local men who come to drink away from the public gaze," my friend said.

I didn't see a single foreign customer at the restaurant that night.

The shadow of fear

On another evening I met a young foreign lady who stood out in the crowd with her thick black, knotted hair and dark skin.

"I'm from Zimbabwe," she said. "It's been six months since I arrived in Kabul."

I had assumed she was British or American.

"This is the problem," she told me. "I can't go out because I'm afraid of being kidnapped. Those who are after Westerners would confuse me with a British or American citizen because they would just look at my skin not knowing that I'm from a poor country."

She had stepped out of her hotel only twice since arriving.

I asked her how she spent her spare time.

"Like these people," she said, referring to other foreigners at the hotel bar. "They gather on Friday nights in heavily-guarded compounds to share their little joys in the shadow of the fear of a possible Taliban attack."

The Kabul Serena Hotel, which was attacked in 2014

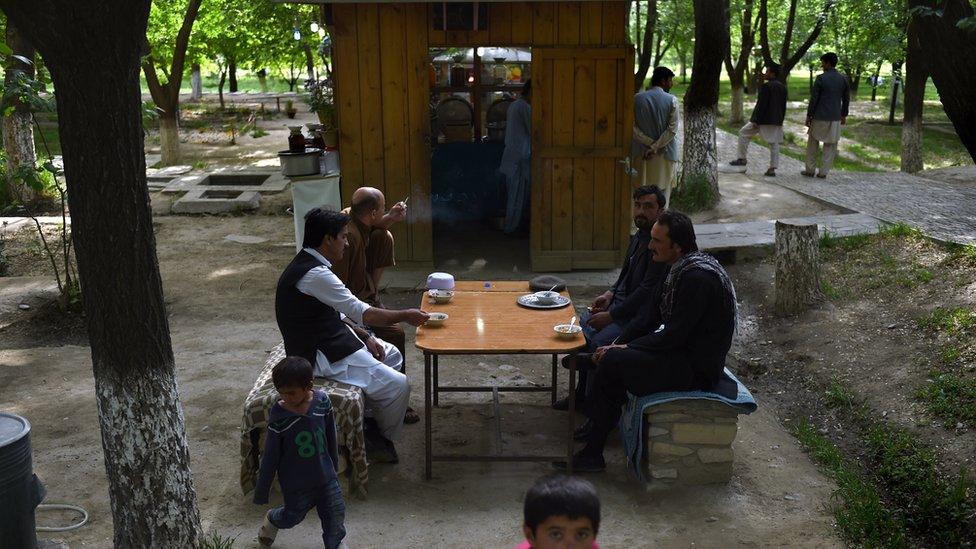

Kabul's historic Bagh-e Babur gardens remain popular with picnickers, despite the security threats

Such fears are not unfounded and foreign visitors are well briefed about potential dangers. Earlier this year, a suicide bomber killed two people at a French restaurant popular with foreigners in Kabul.

In January 2014 the Taliban attacked a Lebanese restaurant, killing at least 21 people. Two months later nine people, including four foreigners, died when gunmen attacked diners at the five-star Serena Hotel.

These kinds of attacks have resulted in the closure of many high-end restaurants, meaning the loss of jobs for local Afghans.

The day I headed back to London I met my friend one more time. He lamented how Afghanistan was seen by the outside world.

"The closures of these restaurants and the foreigners' fear of being kidnapped have contributed to a distorted image of Afghanistan abroad," he told me.

"Many foreigners who come to this country are not able to go out and interact with ordinary Afghans. How do you expect them to have a proper picture of this country and its people?"

- Published10 March