Viewpoint: Life in the land of 'candle princesses'

- Published

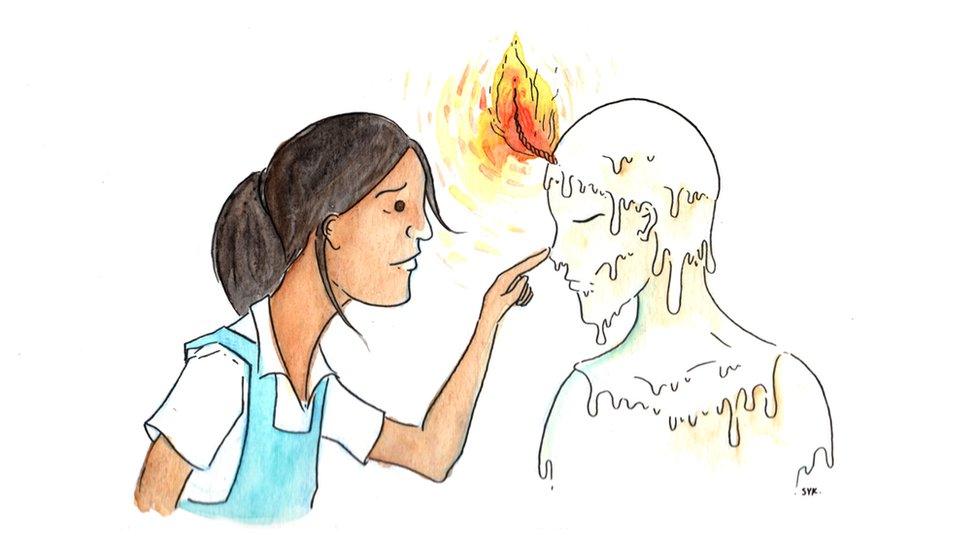

Fair skin is more of a beauty ideal than darker skin across Asia - in Malaysia fair-skinned women are known as "candle princesses". Writer Eris Choo shares a frank account of growing up in a society with rigid beauty ideals.

Have you ever heard of a candle princess? No, it isn't an obscure fairy tale.

In Malaysia, a "Puteri Lilin" is someone who can't stand being in the sun for too long. Just like a candle, she'd melt from the heat. It originates from an ancient Malay folktale.

The term is now used to refer to people who avoid the sun like the plague, for fear of getting darker. I've never been called one but I certainly know my fair share of candle princesses.

You can spot them easily with their talismans the mini-umbrella, protector of fair-skinned girls everywhere. Outdoor sports like basketball and volleyball are taboo for them. They favour daintier indoor sports, like ping pong.

I had one "candle princess" friend who would walk out with me, but when it came to going out in the sun, would unfurl her umbrella. Growing up, I used to think it was funny, watching girls try to cross our school yard without even a ray of sunshine touching their skin.

It stopped being funny when I found out why it was much better to be fair than dark-skinned in Malaysia.

The fairest of them all

In Asia, the preference for light skin has less to do with race and more with class.

Malaysia has the same prejudices as many societies around the world and just like the Evil Queen from Snow White, we are a nation obsessed with being fair-skinned.

Among the Malaysian Chinese community, fair skin has long been considered "pretty". And I'm sure many of Malay and Indian ancestry would agree.

Dark skin has historically been associated with peasants, farmers and labourers. The rich didn't have to work on the fields, and therefore, had fair skin.

And the media hasn't helped, often favouring light-skinned actors with so-called "pan-Asian looks". Whitening creams are also often best sellers.

Being a basketball player in high school, I was quite tanned.

But I remember an incident when I sauntered into class with my team mates after a gruelling game. A classmate started laughing, and called us "Africa". Everyone else picked up on it and started howling hysterically.

We didn't stop playing because we loved basketball too much.

But after that incident I began to avoid taking photographs. I felt ugly standing next to friends with "normal"-looking skin. It also didn't help that these ideas were often reinforced among my own family.

Every time I went back for family gatherings, there were only two things my relatives would comment on: if I had lost or gained weight, and whether I had gotten darker or fairer.

This will be familiar to many across Asia, but even worse was that I felt validated by their "praise" and ashamed when I couldn't achieve those ideals.

Sun bathing: probably a big taboo with candle princesses

I only truly broke free from this cycle of self-loathing a few years ago by hanging out with people who were positive and encouraging.

I also met someone who told me I was beautiful every day, and who really believed it. Slowly, I started believing in it too.

And it's true that the term itself is not entirely a compliment: it has a tinge of scorn shot through with the awareness that a candle princess is delicate, to be taken care of, not robust.

The advertising industry is part of this. A recent TV ad showed a model dodging the sunlight and then a voiceover: "The sun can damage not just your looks and skin, but your confidence! Use X brand for fairer, healthy looking skin!"

But this is a marked improvement from older ads, which blatantly promoted having fairer skin just to look "attractive".

The candle princesses in Malaysia are still here but there are a few, small signs that society might just be changing.

Illustrations by Shing Yin.