Gates's advice for the world's most cash-strapped nation

- Published

The world's richest man is visiting the world's most cash-strapped nation.

In an address to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his cabinet on Wednesday, Bill Gates said: "The bold move to demonetise high value denominations…is an important step to move away from a shadow economy to an even more transparent economy."

When I met the Microsoft founder in a lounge in one of Delhi's many grand hotels it became clear that, perhaps not surprisingly, he sees technology as key to India's future prosperity.

He believes India is on the verge of a digital financial revolution that goes well beyond the online payments and plastic cards that most banks already offer their customers.

He is looking forward to the entry of players such as mobile phone companies and others into the consumer finance market - something the Modi government has said it is poised to authorise.

These services use software first developed in Africa to transform your mobile phone into a kind of digital bank branch, allowing you to pay for goods and services, transfer money and even get loans at the push of key.

Mr Gates believes that India will become the world's most digitised economy

Mr Gates believes that the pull of these services, together with the push of demonetisation, will cause Indians to stampede into what he calls the "digital realm".

"All of the pieces are coming together," he told the Indian prime minister. "I think in the next several years India will become the most digitised economy, not just by size but by percentage as well."

He is clearly thrilled by the prospect, but not because he sees potential business opportunities for the software company he founded back in the 1970s. He is excited because he thinks it will dramatically reduce poverty in India.

Mr Gates gave up control of Microsoft almost a decade ago. He and his wife now work full time with The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, external, the richest charitable organisation in the world, which he set up back in 2000 and into which he has now poured more than $36bn (£29bn) of his fortune, external.

The aim of the foundation is to reduce poverty and ill health around the world, and India is an important focus for its efforts, external. Since 2010, the foundation has invested more than $1bn (£800m) in India, more than in any other country outside the US.

That is because while India may be the fastest-growing large economy in the world, it still has more malnutrition and infant mortality than any other nation.

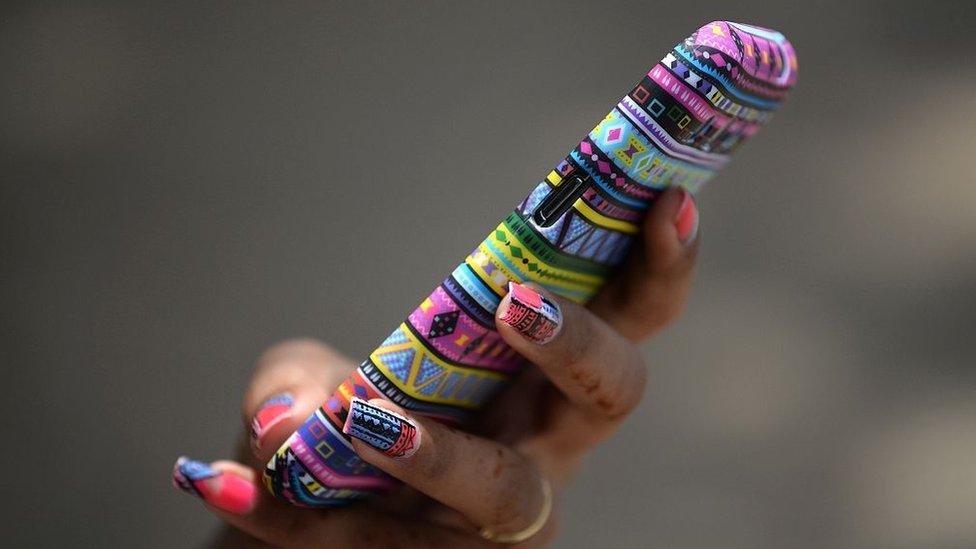

The Indian government recently declared that 1,000 (£12) and 500 (£6) rupee notes would no longer be valid

Demonetisation matters, he says, because together with these new payment services, it will begin to draw even the very poorest out of the cash economy.

That will help reduce poverty, and hence disease, Mr Gates says, because the cash economy is expensive, inefficient and time consuming.

A move into the digital realm will cut transactions costs, allow the government to pay benefits directly to those who need them, and make credit easier and cheaper for everyone.

At the moment, 7% of Indians are driven into poverty each year by unexpected health costs.

Cheap credit based on rigorous risk scoring can smooth bumps like that.

It can also open opportunities for even the poorest to start businesses, and invest in the country's future by buying extras such as schoolbooks for their children.

But the benefits should go even further than that.

Mr Gates believes that India's culture of technological innovation makes it perfectly poised to develop new digital financial services.

"I think India will become the leader," he says.

The process of digitisation should also help India grow its tax base.

Statistics published earlier this year showed that just 1% of Indians paid income tax in 2013.

"Broadening the base of the income tax in terms of equity, in terms of funding these massive healthcare needs, that's certainly the path the government needs to go down," he says.

Mr Gates fears that "people would be worse off" if Donald Trump ends trade agreements

Overall, Mr Gates is very optimistic about the prospects for India.

"This is an amazing and pivotal moment in India's history," he told Mr Modi.

"If India focuses on the right things it will improve the human condition at a scope and scale never witnessed before."

But he sees risks ahead, for India and the world.

He fears the trend towards increasingly free trade between nations is under serious threat.

He is clear about the consequences: "people would be worse off".

But when I ask if he is worried by the prospects of Trump presidency, his tone changes.

"Trump has said a lot of things," he says.

"The key thing is, in a very calm way, now that he is going to become president, to look at what he actually does.

"And everybody is hoping… that some of the things that clearly resonated with the voters, that he is able to move in that direction without throwing out some of the benefits in areas like free trade."

And on that diplomatic note, Mr Gates vanishes through a door and off to his next meeting. The interview is over.

- Published9 June 2016

- Published27 September 2015

- Published22 January 2016