Why South Korea's corruption scandal is nothing new

- Published

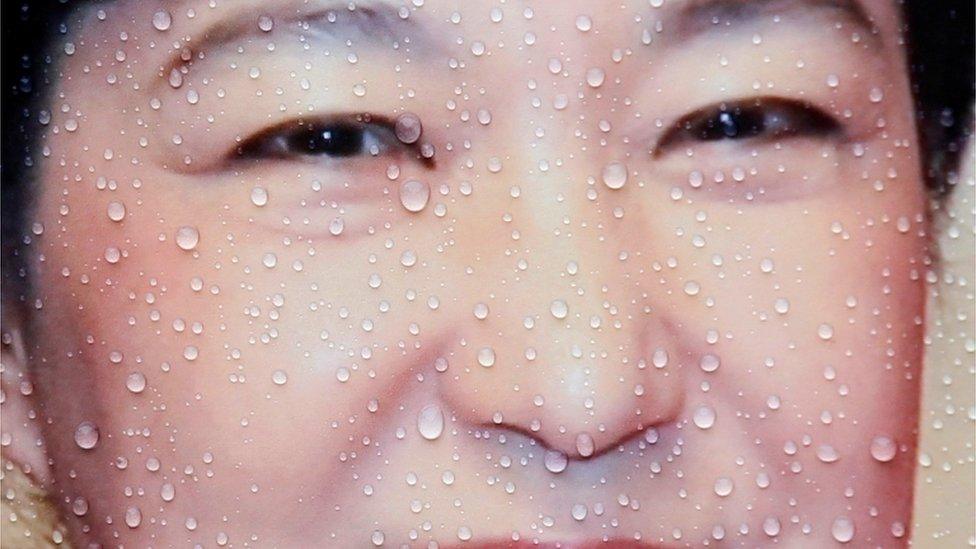

A scandal is swirling round the South Korean president. Park Gun-hye has been accused by prosecutors of being complicit in a scheme to pressure big companies to donate millions of dollars to funds controlled by a very close friend.

Some of the biggest family-run firms - Samsung, Lotte, SK - have been raided, along with various government offices. Ms Park's lawyer says prosecutors have "built a house of fantasy" but the allegations highlight a historical paradox, say the BBC's Stephen Evans in Seoul.

In everyday life, it seems like one of the most honest countries on the planet - and yet president after president has ended up entangled in scandals over money. The cloud of corruption rarely lifts from the presidential palace.

Take the last four presidents: Kim Dae-jung (1998-2003) was himself untainted but two of his sons were jailed for taking bribes. Roh Moo-hyun (2003-2008) committed suicide after leaving office as corruption investigators closed in over allegations he accepted $6m in bribes.

Lee Myung-bak (2008-13) apologised after his elder brother was sentenced to two years in prison for accepting $500,000 from businessmen in return for influence over the government.

And now the current president, Park Gun-hye, is accused by prosecutors of being complicit in a scheme to pressure millions of dollars out of big companies.

Roh Moo-hyun took his own life six months after leaving the presidency

There does seem to be a pattern: even if the president seems untouched, those close to him - or now her - harvest opportunities for reaping cash from their closeness to power. It's sometimes called "pay to play".

And all in a country where you can leave a full wallet on a table to reserve a place in a bar in the full confidence that it will not be stolen. You can forget your camera in a public place and return unworried to find it in the same spot or even moved to the side and left safely under a shelter.

But all the presidents of the democratic era - not to mention the heads of the family-owned conglomerates, the so-called chaebols - have been soiled by corruption, either personally or by their close friends and family leveraging their ties to the leader.

Sometimes politics and business go hand-in-dirty-hand together: a chaebol head goes to jail and then the president pardons him.

Why is this? How do you explain an almost naive honesty at the bottom and an unreliable moral compass at the top?

Firstly, honesty is not such a simple quality. We can be honest in some circumstances and not in others. Even though there is a high level of trust between people in South Korea, other measures of honesty paint a less idyllic view.

Researchers at the University of East Anglia in the UK devised an experiment to test personal honesty in 15 countries. They got people from each country to toss a coin privately and then report the result.

Demonstrators have demanded President Park's resignation

The participants were told they would get more money if heads came up than tails (even though the actual probability was 50:50). The more the people involved reported that they had had more than 50% of heads, the more dishonest they were deemed to be.

South Korea came out low (though not quite as dishonest as China, but way below the UK, the most honest country on the basis of this particular test).

Away from the test and back in the real world, dishonesty at the top (in business and politics) is not unknown. One of the reasons is the way South Korea is run, with the government historically taking a strong role in the direction of the economy.

The government of Park Chung-hee (the current president's dictatorial father) started the modernisation of South Korea by directing chaebol heads to establish industries.

As Professor Robert Kelly of Pusan National University put it: "The opportunities for graft (political corruption) are as obvious as they are extensive. These are the sorts of relationships that have repeatedly done-in Korean political and chaebol elites. Until the state steps back from the economy, such scandals will continue."

There are also deeper roots, according to Professor Kyung Moon Hwang of the University of Southern California. Confucianism "values not only hierarchy in social relations but also reciprocity, the idea that one must repay kind treatment".

President Park and her father, Park Chung-hee, in 1977

"This is in general a good thing, but in the political arena, this can lead to officials expecting something in return for their decisions."

Before the current democratic era, which has only been going for 30 years, despotism, Professor Hwang said, triggered "the impulse to pay bribes, regardless of the official's wishes, knowing that the official will feel obligated to return the favour".

On this argument, old habits die hard, and democratically elected politicians retain old despotic ways of thinking.

But there is a hopeful side to this: prosecutors do pursue miscreants, people protest against corruption in their hundreds of thousands, new laws do get passed (like a recent cap on the amount of money which can be spent on entertaining public servants, from politicians to teachers), and the press is tenacious.

As Professor Kelly put it: "Corruption in South Korea is often uncovered and subject to scrutiny. Prosecutors pursue it and the public gets incensed.

"Future cheaters," he added, would have to reckon on being caught and punished. "Cleaning out the dirt may be ugly but it is happening."

- Published8 November 2016

- Published12 November 2016

- Published23 November 2016