What will Trump mean for South East Asia?

- Published

Exit stage left for the US?

President-elect Donald Trump might come as a shock to many Americans - but for the 600 million people of South East Asia the reaction could well be: "Seen it all before."

More than a few Thai people have noted their country was a trend-setter, electing billionaire telecoms tycoon Thaksin Shinawatra by a landslide 16 years ago, on promises to shake up the old order.

Mr Trump, though, might prefer not to dwell on that comparison, as his Thai trailblazer ruffled so many establishment feathers that he and his allies were blocked by a succession of military coups and court verdicts, with democratic governance suspended in 2014.

Billionaire Thaksin Shinawatra was deposed by the Thai military in 2006

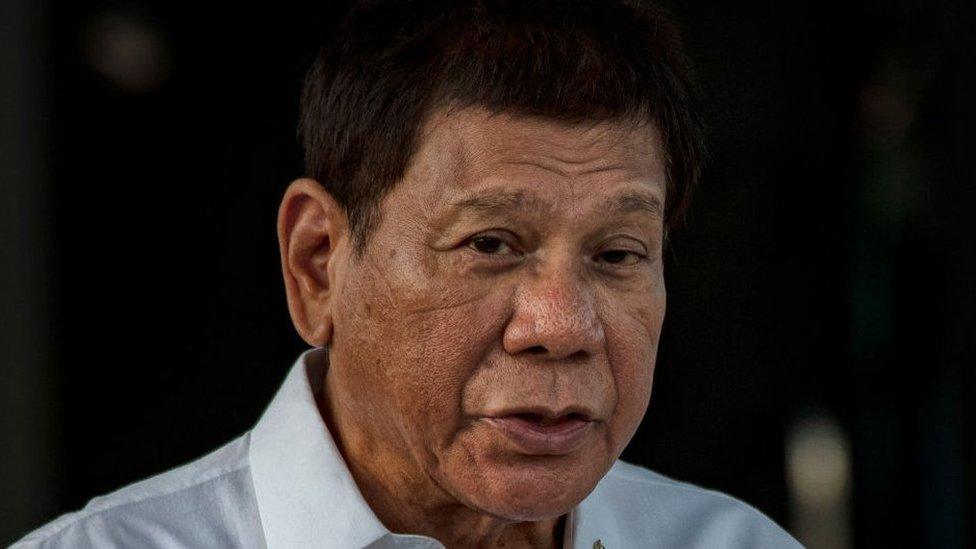

And then there is the man they were calling "Asia's Trump" months before the shock result in the US.

Rodrigo Duterte swept to office in the Philippines on dramatic pledges to tackle crime, shake up his country's foreign policy, and change its constitutional order.

On the first two, he has stuck to his word, leaving thousands dead in a violent anti-drug campaign and tearing down the long-standing military alliance with the US.

President Duterte insulted President Obama after the US expressed rights concerns

In much of this region, democratic values, which had appeared to advance in the early part of the globalisation era of the 1980s and 90s, are now losing ground.

Thailand is under a military government that routinely curtails civil liberties.

In Malaysia, opposition politicians are being prosecuted under a colonial-era sedition law, as Prime Minister Najib Razak battles a massive corruption scandal.

And in the Philippines, President Duterte has dismissed concern over the huge spike in extrajudicial killings.

Cambodia's strongman Hun Sen, who has ruled for three decades, has reduced the political opposition to impotence by relentless legal harassment.

Even in Myanmar, also known as Burma, where last year's election of Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy raised hopes of a new beginning, the harsh treatment of the Rohingya minority and state pressure on journalists continues.

So when President Barack Obama announced his "pivot" to Asia five years ago, rebalancing US foreign policy towards this region, most governments welcomed the prospect of improved trade and US military engagement to balance the rising influence of China - but they did not welcome the American comments on human rights that went with it.

A Trump administration, then, may come as a relief to some.

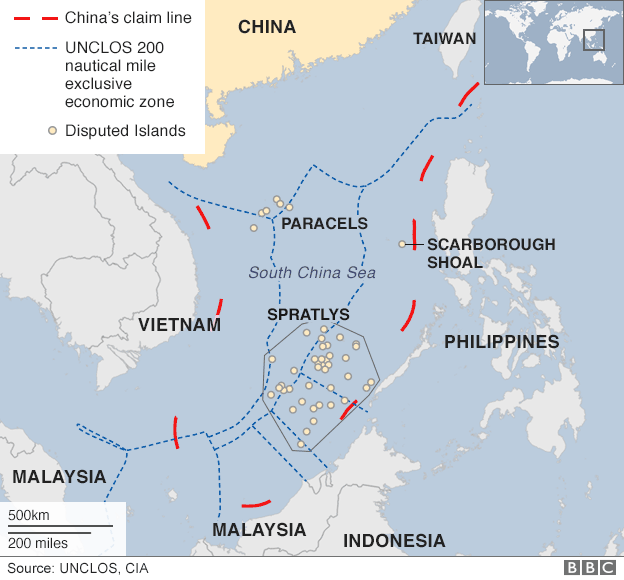

Many countries in the region have territorial disputes with China

Mr Trump has shown no interest in a values-based foreign policy stressing human rights.

Already President Duterte has noted the commonality of their brash speaking styles and suggested he might reconsider his threats to downgrade ties with the US, although he still wants to cancel the agreement his predecessor signed to allow US troops to use bases in the Philippines.

Thailand, which has bristled at occasional US expressions of concern since the last coup, may be a lot happier with a more hands-off President Trump.

Hun Sen openly backed Donald Trump before the election.

Prime Minister Najib was quick to congratulate him after the election, noting their past golfing partnership and perhaps hoping a Department of Justice investigation into allegations that billions were looted from his brainchild investment fund, 1MDB, may move more slowly under President Trump.

What is clear is that under President Trump the "pivot" is finished.

Malaysia's Najib Razak exchanges a cool glance with President Obama at a recent APEC summit

President Obama's rebalancing leaned heavily on:

the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade deal among 12 Asia-Pacific countries

bolstering existing US military partnerships with Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea,

establishing closer military ties with other countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia

playing a bigger role in regional summits such as the annual ASEAN Regional Forum and the East Asian Summit (EAS)

Mr Obama was the first US president to attend the EAS every year.

But during the US election campaign, both parties attacked the TPP, reflecting growing public hostility to trade deals, which are believed to have cost American jobs.

Mr Trump has said it will be the first deal he tears up.

He is also unlikely to take much interest in Asian summits and has promised to get tough over what he says are unfair trade practices by China.

His isolationist tone could well dictate a US retreat from this region, leaving China the de facto dominant power in South East Asia, something that will surely worry Japan and South Korea.

Singapore, which had military vehicles seized by China recently, is one ally concerned about a possible US retreat

However, there is so much we still do not know about a Trump foreign policy that it is difficult for governments here to formulate policy responses yet.

And, according to Thitinan Pongsudhirak, director of the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, President Obama's achievements here were often less than they appeared.

"The Obama 'pivot' ultimately proved shallow and unreliable, underpinned by rhetorical footwork with little substantive thrust," he says.

"It was akin to the inkless 'red lines' drawn in the Middle East, where US leadership was confined to 'leading from behind', eschewing boots on the ground in favour of remote-controlled drone attacks.

"Leading from the back often meant not leading at all.

"Obama is a popular leader because of his personal appeal, but his policy record is mixed.

"His administration too often walked loudly but carried a meek stick."

Japan, here carrying out a joint exercise with US ships in the South China Sea, is worried about a US U-turn

Mr Pongsudhirak is not alone in arguing that the US is already losing South East Asia, with smaller states like Laos, Cambodia and Brunei firmly under strong Chinese influence, and the larger states looking to China now more than Japan, the US or the EU for investment and loans.

And he says that trend will accelerate under President Trump.

The US has in many ways moulded modern South East Asia, fighting a destructive war in Indochina in the 1960s, decisively influencing the political shape of states such as Thailand and the Philippines, and, with Japan, initiating the era of trade-based globalisation in the 1980s.

It has had a profound cultural influence on most South East Asian societies and has been instrumental in disseminating the values of civil rights, media freedom and government accountability.

This influence has at times been resisted and resented. But if the US does now turn inward, and away from Asia, it may also be missed.

- Published22 November 2016

- Published22 November 2016

- Published22 November 2016

- Published23 January 2017

- Published12 July 2016

- Published25 July 2016

- Published11 March

- Published26 August 2016

- Published11 November 2011