Pakistan 'honour': Tracing the final steps of a woman searching for love

- Published

Sarakat Bibi left a husband she didn't love for Mohammad Somar (right)

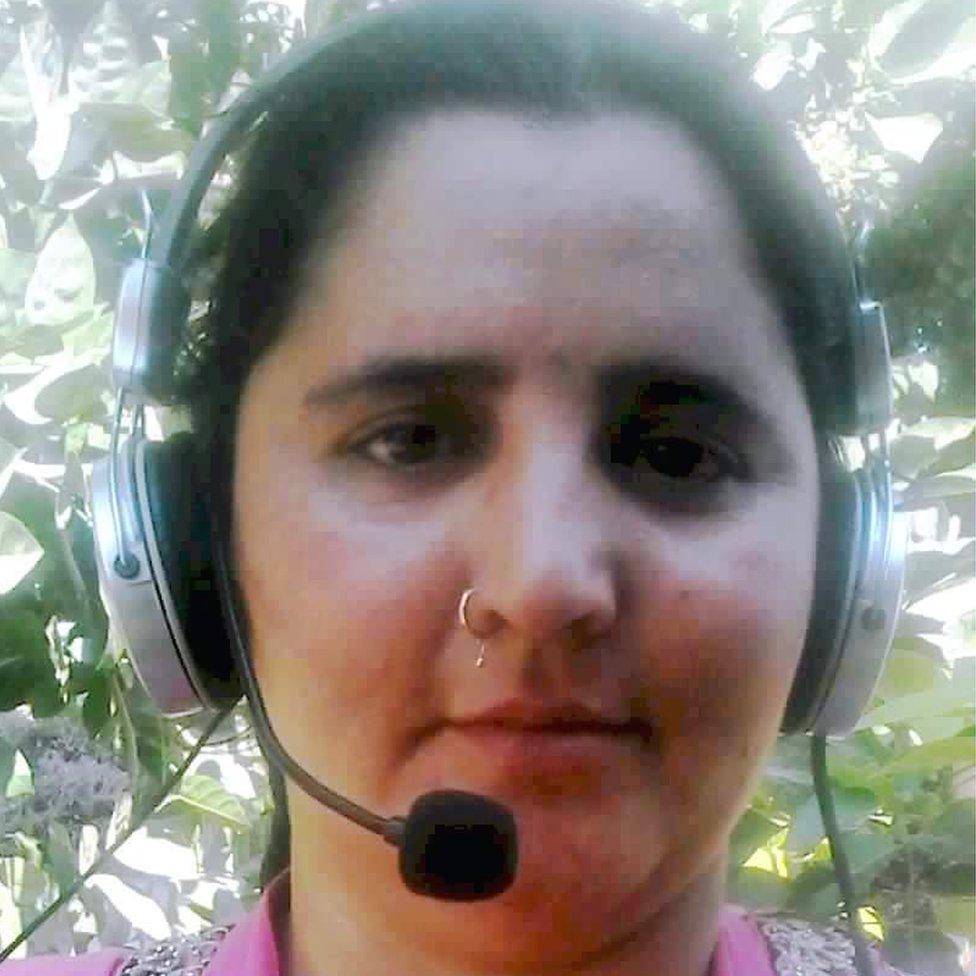

Did Sarakat Bibi finally fall into a trap? M Ilyas Khan pieces together the life, love and mysterious last movements of a Pakistani woman who it's feared was killed for "honour".

Sarakat Bibi spent years on the run. She was last heard of a year ago, aged 37, when she rang home.

But her problems began many years before when, aged 14, she refused a marriage with her cousin, arranged by her father.

The 'marriage from hell'

"She didn't like her cousin and his entire family," said her mother, Husanzadgai. "And she was brave, so she went to her father's elder brother and told him so. It sent shockwaves through the family."

Husanzadgai says Sarakat was physically and verbally abused by her in-laws

As elsewhere in South Asia, the Pashtun tribes of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province in the north-west follow a strict patriarchal code in which all decisions for women are made by men.

Sarakat's father was furious and left her with little choice - he picked up a gun and told her to agree to the proposal or prepare to die.

The woman who survived an 'honour killing'

The model and the mullah: Pakistan's 'Kim Kardashian'

Mother 'burnt her daughter to death'

On the day she was taken as a bride to her husband's house in Barawal Bandi village, in mountainous Dir district, her mother-in-law taunted her for having refused the match and threatened to fix her.

Barawal Bandi is high in the mountains in the north-west

Over the next 20 years, Sarakat "lived through hell," Husanzadgai said. "She faced verbal abuse and physical violence."

Sarakat, the eldest of seven - four brothers and three sisters - bore five sons, but that didn't earn her respect.

"She was getting hardened too," he mother said. "When things got really ugly, she would come over to our house. I would then plead with her to go back home as it could taint her father's good name."

A wrong number and an escape

But one day in April 2012, when her husband Roghan Shah was away on business, Sarakat disappeared, leaving behind her children, the youngest just four years old. She travelled first to Peshawar and then south, far from her family.

Seven months earlier she had taken a call that would change her life. The man on the other end of the phone was hundreds of miles away, in Sindh province, and he had rung a wrong number.

"That was my first encounter with Sarakat," said Mohammad Somar. "She said hello, and then something in Pashto which I couldn't understand. I spoke back in Urdu, and she disconnected."

Mohammad, 34, lives in Warwalo, a village 1,100km (680 miles) south of Barawal Bandi, along the fertile Indus River plains.

Mohammad Somar's house in Warwalo is at the other end of Pakistan

His father married him off when he was just 12 and later put him in charge of the four-acre family farm where wheat, cotton and sugarcane grew.

Farming was good and Mohammad bought shares in a motorcycle dealership, boosting his income. But there was a void in his life. He said he never felt any real love for his wife, with whom he had eight children.

When he heard Sarakat's voice in September 2011 he became desperate to meet her. He had always admired Pashtun women for their courage and good looks, he said.

So even though Sarakat hung up the first time, he persisted and over the following days and weeks she gradually came round to talking with him.

Life on the run

Seven months later, Sarakat left her home in the mountains.

"I went to Peshawar to pick her up," said Mohammad. "We drove in a bus to Sindh, and went straight to a court in [the nearby town of] Ghotki where we got married."

"I wanted to keep the marriage secret from my family and put her up at a house in Ghotki, but she was afraid I might take advantage of her and then abandon her. She wanted to go to my house."

Mohammad Somar said Sarakat tried for a child

Over the next month, his first wife left him, his in-laws turned into his enemies and Sarakat's continued use of her mobile phone gave away her location to the police, allowing her father and husband to track the couple down.

They were arrested on an abduction charge and then released after they produced proof of their marriage. But their troubles were only just beginning.

Soon afterwards, Mohammad was named by the police in a criminal investigation. His house was raided in October 2012 but he was alerted by a friend in the police and the couple escaped.

They fled to Hyderabad, 400km to the south, where they lived in hiding for the next two years.

"We survived on money we had saved from the farmland, the money I got by selling my share in the motorcycle business, and occasional handouts from Sarakat's mother and sister, who knew we were in trouble," Mohammad said.

But things got worse. Mohammad developed a kidney stone and was bed-ridden for months. Sarakat had a miscarriage.

"She had wanted a child so badly," Mohammad said, his voice choking. He sobbed for a minute or so. "She wanted someone of her own in a strange land. She cried for weeks."

Return to court

Driven by hunger and isolation, the couple finally decided to go back to Mohammad's village. He had persuaded some old political contacts to stop the police from arresting him until he had arranged bail.

Inspector Zahir Shah is the officer in charge of investigating the case

But by that time, he had been named in as many as 16 criminal cases, he said. Back home, Mohammad spent most of the next year attending court hearings, trying to run his farm and fighting failing health.

Then on 3 December 2015, disaster struck. Sarakat was arrested.

How that happened is not fully explained, but it appears she may have approached the authorities for protection after falling out with one of Mohammad's relatives at a market which she had visited unaccompanied.

Whether she wanted to leave her life in Sindh is not clear - nor is her apparent decision to contact the police, given all the reasons she had to mistrust them.

"I went to the court to see her but she refused to come with me," Mohammad said. "She didn't even talk to me, she just waved goodbye from afar. She was crying."

He believes her relatives paid the police to have her taken back to Peshawar so they could redeem their honour.

No one can say for sure if he is right, but we know what happened next.

The final phone calls

"On 5 December, my phone rang and when I picked up, it was Sarakat," said Husanzadgai, her mother. "She said she was in Peshawar with a policeman from Sindh who needed to hand her over to a blood relation. I was in shock."

Her husband and three elder sons were working in Saudi Arabia so she asked her fourth son, Khalid Mehmood, then aged about 19, to go instead.

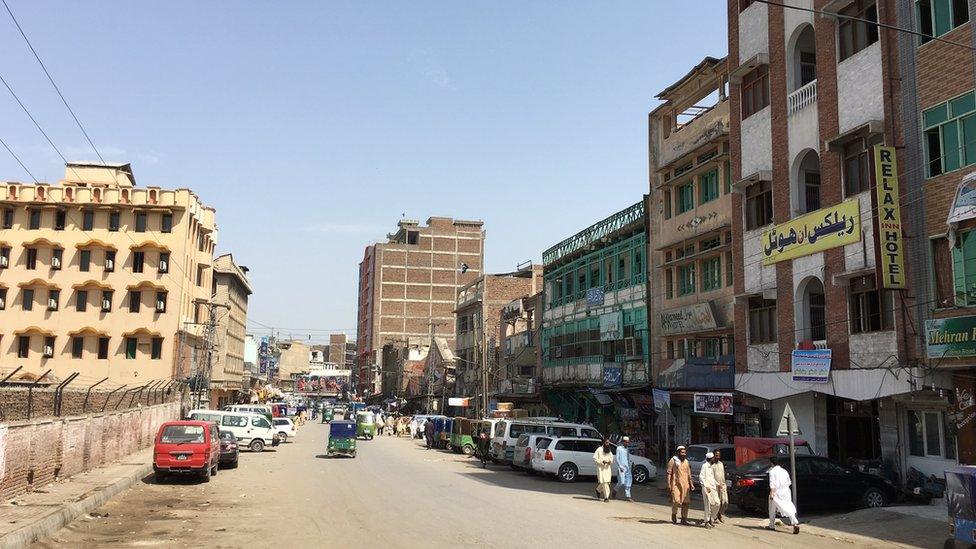

Sarakat stayed in the Relax Hotel in Peshawar

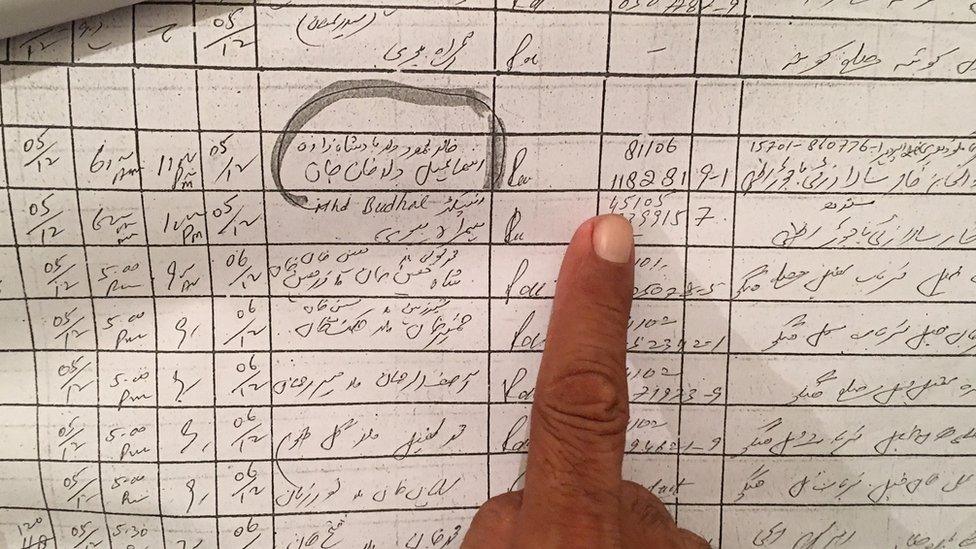

The guest register shows she was in Room 106, booked in Mohammad Ismail's name

He later told a court in Peshawar that he had found his sister in a cheap hotel room with a Sindhi policeman in plain clothes, and a local man, Mohammad Ismail, in whose name the room had been booked.

Khalid Mehmood signed the papers, sending the policeman away, but his sister refused to go with him, telling him that her former husband's family would kill her if she set foot in her village. She persuaded him to go back alone.

Later that day, she called her mother again, who says she told her of another man in her life: Abdur Rahman.

He was, she told her mother, a businessman who had a comfortable house in Peshawar and wanted to marry her. How and when she came into touch with him remains unclear.

But the next day, she told her mother that she had been brought to a huge compound where several women put henna on her hands and feet and gave her a wedding dress to wear.

"She sounded satisfied and relieved. But that evening her phone went dead," her mother recalls.

'I knew then she was trapped'

The day after, Sarakat's father called her mother from Saudi Arabia. He said that a brother of Roghan Shah, Sarakat's first husband, had rung up from Pakistan to pass him the message that Sarakat was in their possession and they would now redeem their honour.

Sarakat's father wanted Husanzadgai to go to the police.

"I knew then that she had walked into a trap," Husanzadgai said.

Police investigations later showed that, after Sarakat's brother left the hotel, Mohammad Ismail, an employee of the local tribal Levies force, took her to a residential compound in the Shahkas area of Khyber tribal region, just west of Peshawar.

Ismail confessed in court that he did this as a personal favour to a colleague, Habibur Rahman, who used the fake name Abdur, it is alleged, to contact Sarakat.

Mohammad Somar believes Sarakat's first husband somehow trapped her via a fake Facebook account and may have passed details of the account to Rahman.

Rahman was later arrested, and it transpired that he was a distant cousin of Roghan Shah. Police also arrested Shah's brother, Falak Niaz, who had been outside the compound where Sarakat was taken.

Mobile phone data for all three men corroborated Ismail's statement that they were present in the area at the time Sarakat was delivered there.

A search for love

So did she really walk into an elaborate trap sprung by her former husband's family?

The telephone calls seem to suggest that she did.

But a number of elements in Sarakat's story remain unexplained to this day.

We may never find out exactly what happened to Sarakat Bibi

Assuming it was a trap, she had first to be lured with a false promise of marriage. Others must also have been taken in, including presumably the women who hennaed her and made her ready for the wedding day itself.

But seeking retribution in this way is not unthinkable in Pakistan's "honour culture".

Then there remains the unanswered question of how long she had known the man she called Abdur Rahman, if he was the real reason for leaving Sindh.

Mohammad Somar, who is living at his farm with two of his children, says Sarakat had tried to leave several months before she ended up in police custody. Did she spend months making plans with Rahman, lured into believing he was her way out?

And how much did her mother and sister, with whom she'd remained in touch, know of her plans? Had her young brother been primed to leave her in the Peshawar hotel room so she could make a new life?

Answers may come out in court. The three men are in custody, awaiting trial.

But what is clear is Sarakat Bibi spent her life looking for a man she could love and trust. Forced into a marriage and a life she never wanted, she managed to escape and reinvent herself once.

Her mother believes the final attempt to find love once again, and lasting happiness, was just a cruel trick that resulted in her death.

But with no body, no murder weapon and all three men denying charges of kidnapping or murder, proving that will be difficult.

- Published21 October 2016

- Published21 July 2016

- Published8 June 2016

- Published6 October 2016

- Published17 March 2016

- Published7 January 2014