100 Women: How South Korea stopped its parents aborting girls

- Published

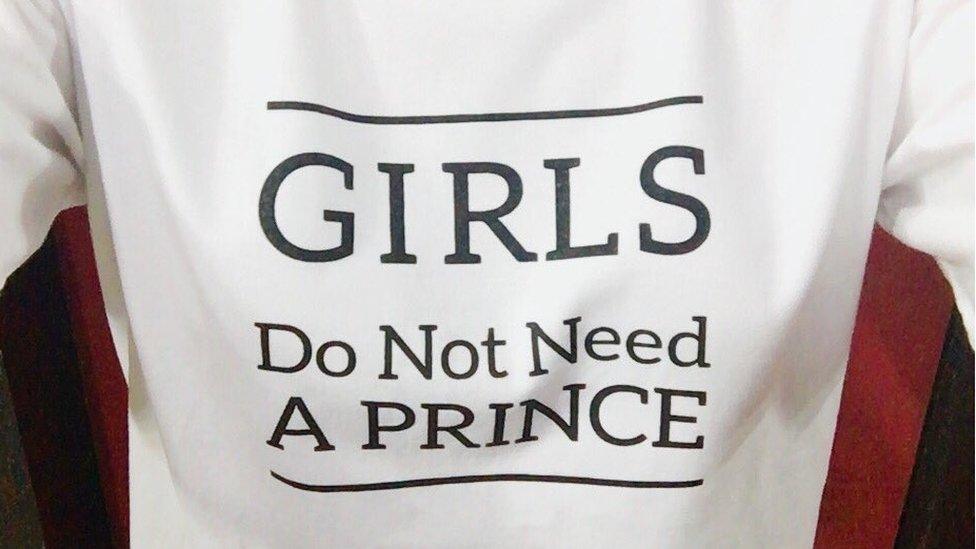

Daughters were traditionally valued less than sons in South Korea

For every 100 baby girls born in India, there are 111 baby boys. In China, the ratio is 100 to 115. One other country saw similar rates in 1990, but has since brought its population back into balance. How did South Korea do it? Yvette Tan reports.

"One daughter is equal to 10 sons," was the message desperately being promoted by the South Korean government.

It was some two decades ago and gender imbalance was at a high, reaching 116.5 boys for every 100 girls at its peak. The preference for sons goes back centuries in Korean tradition. They were seen to carry on the family line, provide financial support and take care of their parents in old age.

"There was the idea that daughters were not regarded as part of their own family after marriage," says Ms Park-Cha Okkyung, the executive director of the Korean Women's Associations United.

The government was looking for a solution - and fast.

In an effort to reduce the incidence of selective abortions, South Korea enacted a law in 1988 making it illegal for a doctor to reveal the gender of a foetus to expectant parents.

At the same time women were also becoming more educated, with many more starting to join the workforce, challenging the convention that it was the job of a man to provide for his family.

It worked, but it was not for one reason alone. Rather, a combination of these factors led to the eventual gender rebalancing.

South Korea was acknowledged as the "first Asian country to reverse the trend in rising sex ratios at birth", in a report by the World Bank., external

In 2013, the ratio was down to 105.3, a number comparable to major Western nations such as Canada.

Rapid urbanisation

Monica Das Gupta, research professor in sociology at the University of Maryland who has studied gender disparity across Asia, says factors other than legislation are likely to be the most significant in accounting for this change.

A legal ban can "dampen things a bit", but she points out that "seven years after the law [was instituted] sex-selective abortions continued".

Rather she attributes the change to the "blistering pace" of urbanisation and industrialisation in South Korea.

While the country was predominantly a rural society there was great emphasis on male lineage and boys staying at home to inherit their fathers' land.

But in just a few decades a large part of the population has moved to living in apartment blocks with people they don't know and working in factories with people they don't know, and the system has become much more impersonal, Dr Das Gupta says.

China and India, though, still have a stark gender imbalance, despite India outlawing, and China regulating against, sex-selective testing and abortions. So why is that?

Dr Das Gupta believes that in China this may be because until last year, the rule that your household registration - known as the hukou system - remained in the village where you were from, regardless of the fact that you might work in the city, meant that there was still an emphasis on male lineage and land ownership, but that this should now start to shift.

But she also stressed that the change is not always linear. As people gain economic advantage they have better access to sex-selective testing and have fewer children, which actually then puts greater emphasis on their gender.

In India in 1961, there were 976 girls for every 1,000 boys under the age of seven. According to the latest census figures released in 2011, that figure had dropped to a dismal 914 and campaigners say the decline is largely due to the increased availability of antenatal sex screening, despite the fact that both the tests and sex-selective abortion have been outlawed since 1994. They say that in the past decade alone, 8 million female foetuses may have been aborted in the country.

But she argues that several factors in India are slowly having a trickle-down effect on attitudes to women including media representation of women functioning in the outside world, and legislative changes enforcing equal inheritance rules and requiring one-third of elected positions be reserved for women.

What is 100 women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. We create documentaries, features and interviews about their lives, giving more space for stories that put women at the centre.

Other stories you might like:

The English girls' school reborn in a Nairobi slum

While South Korea may have rebalanced its population, this does not necessarily equate gender equality, Ms Okkyung argues.

"Even though Korea has a normal gender ratio balance, discrimination against women still continues," the 47-year-old says. "We need to pay more attention to the real situations that women face rather than just looking at the numbers."

Women in South Korea face one of the largest gender wage gaps amongst developed countries - at 36% in 2013., external By comparison, New Zealand has a gap of some 5%.

"Nowadays women go to university at a higher rate than men in South Korea. However, the problem starts when women enter into the labour market," Ms Okkyung explains.

Women are still expected to manage both work and family in South Korea

"The glass ceiling is very solid and there is a low percentage of women at higher positions in offices."

One of the reasons it is harder for women to compete in the workplace is because they are expected to devote their time to both work and family.

"One example is that working mothers have a dilemma, as children in elementary schools come home early after lunch. Therefore, mothers who cannot see a sustainable future in the workplace tend to quit their jobs," says Ms Okkyung.

Dr Hyekung Lee was one of the few Korean women in her generation that did find workplace success.

"I have been very lucky that I was brought up in a very enlightened family. My family had three girls and two boys, and all were given the same support for education," says 68-year-old Dr Lee, who is the chairperson of the Korea Foundation for Women, the country's only non-profit organisation for women.

"But when I became a full-time faculty member in my university, I had to be the only woman professor in my department throughout my 30 years there."

Moving ahead

Generally, attitudes towards women have improved as today's Korean men become more educated and exposed to global norms.

They also inevitably mix with women across all spheres of life, in workplaces, schools or social circles, something that perhaps was not so common decades ago.

Having children makes it hard for women to compete in the workplace, partly because of school hours for younger children

It is amongst the older generation that many still cling on to the preference for sons.

Emily [not her real name], 26, recalls that growing up as an only child, she was always treated equally by her grandparents - until her step-brothers were born.

"I only noticed the difference when my brothers came," she said. "Then I realised that they would never do stuff like the housework."

"My birthday is also one day before my father's so my grandparents didn't allow me to celebrate it because as they said: 'How dare a girl celebrate a birthday before her father?'"

How long will South Korea's women take to catch up?

"I think Korea is at that transitional phase that people are more aware now than previous generations, but it's still not quite equal compared to Western countries," she says.

"I've had friends tell me I can only keep my career if I stay single, and others tell me I've chased away men because I was too bossy on the dates and took the initiative."

She also notes that there is also a substantial difference in attitudes towards women in bigger cities and smaller towns.

"Cities like Busan are more traditional. I've had friends from Busan get a culture shock when they come to Seoul," she says. "In the capital, things are more progressive."

Yet she believes change will come.

"Women in Korea need to be aware that there is gender discrimination," says Emily, who is now studying in the Netherlands. "I didn't know until I left - I thought the way things were was just how they were."

"It's not until you expose yourself to other cultures that you start to question your own. I think things will change, but it will take a lot of time."

Additional reporting by the BBC's Geeta Pandey and Yuwen Wu.

- Published15 August 2016

- Published8 December 2014

- Published29 August 2016