Is Japan’s culture of overwork finally changing?

- Published

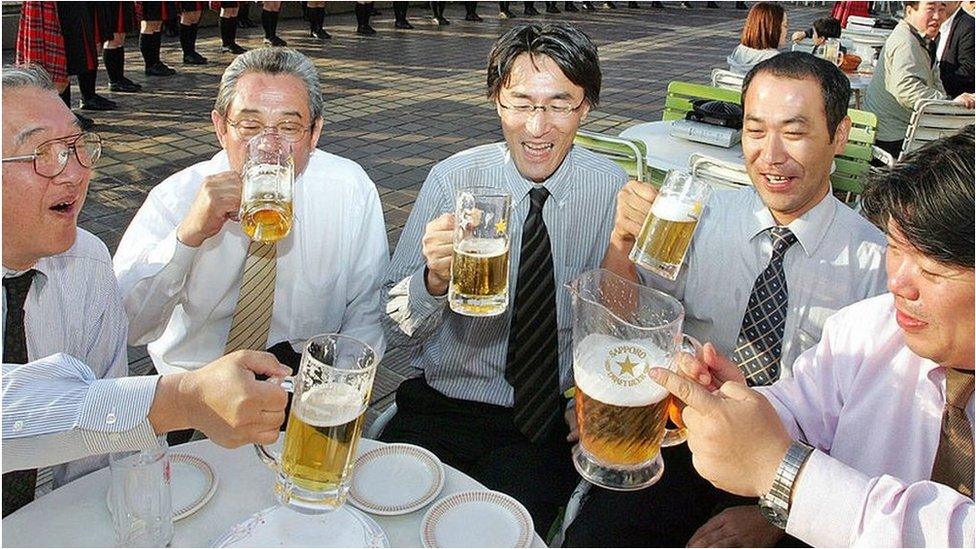

Japanese workers often spend a lot of time with colleagues even after leaving the office

Death from overwork in Japan is such a longstanding problem it even has its own word, "karoshi".

Now the government and business groups are trying to get workers to take a small step to reclaim their lives by leaving work early one day a month.

The scheme, dubbed "Premium Friday", suggests companies make staff go home at 15:00 on the last Friday of the month, starting in February.

It has been given renewed impetus by the suicide of a woman who was working more than 100 hours overtime a month at Japan's biggest ad agency, Dentsu.

Her death was ruled to be a case of "karoshi" and has led to an investigation, an announcement the firm's chief executive will resign and deep concern in Japan at the country's work culture.

But with around 2,000 deaths a year linked to overwork, few believe the voluntary scheme represents anything more than a small step towards changing attitudes and it is unclear how many companies will take it up.

Premium Friday has its own logo

It is not the first time overwork has been seen as a problem nor the first time anyone has tried to do something about it.

Among other initiatives, the government has in the past tried to make employees take more of the leave they are entitled to - Japan's labour ministry says they only take about half - without much success.

The number of public holidays in Japan this year increased to 16 in part aimed at forcing people to take breaks.

The government has also tried to encourage more flexible hours, allowing government workers to start and leave work early in the summer and even switching off the lights in some offices late in the evening, something Dentsu is also now trying.

Workers are increasingly taking the initiative to go home on time some days too, even announcing it on social media to encourage others to do the same.

The death of a Dentsu employee has focused attention on a longstanding problem

But while this has helped change the idea that working excessive overtime is necessarily a good thing, none has had a made much of a dent in the hours themselves.

Around 22% of the population work more than 49 hours a week according to 2014 figures from the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, behind South Korea at 35% but ahead of the US, where 16% of workers put in those kind of hours.

Why change?

For the government and business groups, there is an element of self-interest too.

Japan's economy has stagnated for more than two decades. The situation has been made worse by low consumption spending and a very low birth rate, both of which are aggravated by workers spending most of their waking hours at a desk.

Productivity and efficiency also suffer from firms having staff perpetually on hand, as companies don't invest in labour-saving technologies.

Toshihiro Nagahama, chief economist at the Dai-ichi Life Research Institute, told the BBC that private consumption could rise by as much as 124 billion yen ($1bn; £860m) every Premium Friday if "100%" of those eligible headed home at 3pm on those days.

But he stresses no one knows how many people will take up the idea and that total participation is unlikely, which could mean a much smaller boost to the economy.

Maybe next time dad can come too - increasing family time is one goal

Why would companies and workers not take part? Well, being first to make such a change could be painful.

Companies face higher costs and Japanese workers often feel guilty at leaving their colleagues behind.

"Japanese workers worry about letting down their colleagues" says Mr Nagahama. "They have a strong sense of working as a team."

Having employees work less is especially difficult for Japan's many small businesses, which are battling to keep costs down. The fact that many of them are family-run makes an early walk-out even trickier.

Even with Premium Friday, Mr Nagahama points out some employees may make up the time on other days or even do other jobs in their newly-gained leisure time, which would nullify the point of the scheme.

It is not even clear if the government ministry behind the idea, external will be participating, though Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Hiroshige Seko has reportedly promised that he will not have appointments after 15:00 on those Fridays.

The rare sight of office workers enjoying themselves while it is still light could become more common

Despite doubts about the scheme, supporters hope the modest goal of an early finish once a month combined with the backing of government and industry will encourage uptake, and eventually more fundamental change in workplace culture.

The campaign is also promoting commercial opportunities for restaurants, shops, travel companies and other businesses who could benefit, in the hope that firms will see the benefit of increased leisure time for employees.

Of course, changing deeply-rooted attitudes to work will be difficult. Many previous attempts have failed. But ironically the effort might be helped by Japanese workers' declining corporate loyalty.

Cut adrift by years of restructuring from the lifetime employment bargain that bound their fathers to a single firm, younger Japanese people may find that the chance to head to the izakaya (pub) a bit earlier some Fridays is just the nudge they need to adopt a better work-life balance.

Reporting by Simeon Paterson.

- Published28 December 2016

- Published7 November 2016

- Published20 July 2016

- Published29 October 2015