Is the Philippines' communist insurgency nearly over?

- Published

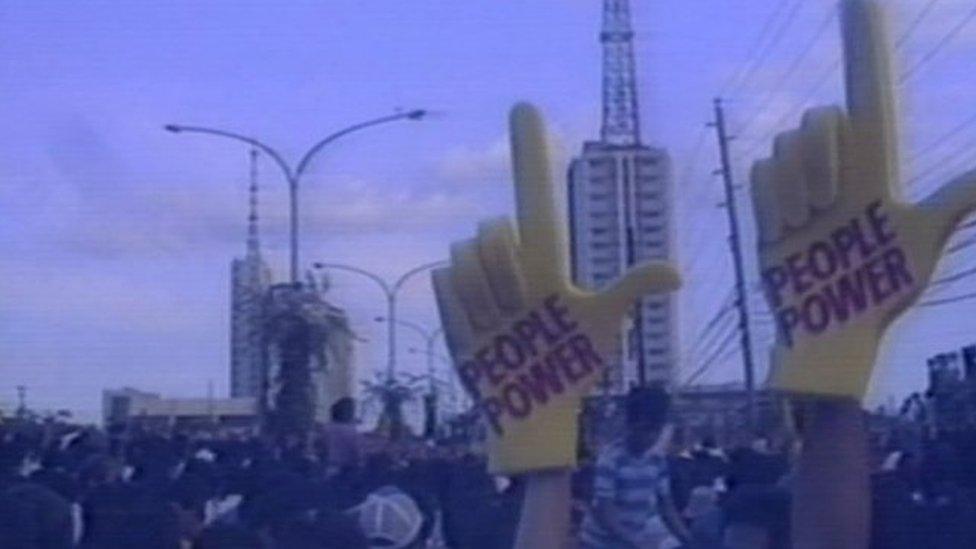

The insurgency is one of the region's longest running

The Philippines government is due to begin peace talks with communist rebels on 18 January which could end one of Asia's longest insurgencies.

President Rodrigo Duterte has said he wants to "walk the extra mile" to achieve peace, in a conflict which has claimed an estimated 30,000 lives since the 1960s. BBC Monitoring's Mark Wilson examines the challenges ahead.

Who are the rebels?

The Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) began its armed struggle in the late 1960s. Its aim has been to overthrow the government through guerrilla warfare. The insurgency was established by academic, author and poet Jose Maria Sison.

The CPP's armed wing, the New People's Army (NPA), is believed to number around 4,000 fighters, down from a peak of 26,000 in the 1980s during the martial law era.

President Duterte shares some of the rebels' left-wing and anti-US sympathies

The NPA has engaged in killings, bombings and hostage-taking across the archipelago, collecting "revolutionary taxes" from businesses in the areas it controls.

Both the CPP and NPA were designated foreign terrorist organisations by the US government in 2002.

The rebels strongly oppose the US military presence in the Philippines and have in the past killed American service personnel stationed in the country.

Since the 1980s they have entered into talks with successive governments, but a peace deal has remained elusive.

What progress has been made?

Mr Duterte wants to end the insurgency and has said he is willing to "walk the extra mile" for peace.

He has tried to revive the peace process and has already held two rounds of formal discussions with the rebels since he took office last year.

The rebels have also called Russia and China imperialists, in statements and secret press conferences like this

The president has attempted to win the rebels' trust through a series of confidence-building measures. These include appointing rebel sympathisers to his cabinet, releasing high-ranking rebels from prison and offering land to NPA members if talks succeed.

The rebels have reciprocated by releasing police officers they were holding hostage.

Both sides have also separately declared a series of unilateral ceasefires, but are yet to agree a joint ceasefire deal.

What are the barriers to peace?

The ceasefires have been marred by the killings of soldiers and rebels.

Government officials accused the CPP of being unable to control its armed wing after four soldiers were killed in an NPA landmine attack in July.

The attack led Mr Duterte to temporarily lift the government ceasefire.

Days later, an NPA rebel was killed in a battle with the military in Surigao del Norte province.

The rebels are also demanding social reforms

The rebels, who say they will not give up arms even if a deal is reached, have accused the military of using Mr Duterte's drug war as a pretext to mount operations in rebel areas amid the ceasefire.

A real sticking point in recent months has been the issue of freeing around 400 detained rebels.

The CPP demands that the government grant a general amnesty to these rebels as part of negotiations.

After Mr Duterte refused, insisting that the rebels must first agree to a joint ceasefire deal, the rebels accused him of "capriciously changing his mind" on the issue.

Rebels say they will not give up their arms even if a deal is reached

Since the last round of talks in October, the rebels have also taken issue with some of Mr Duterte's policies at home and abroad.

They have criticised both his warming relations with Russia and China and his move to allow a hero's burial for late dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

What happens next?

At the forthcoming talks on 18 January, to be held in Rome, the two sides will aim to reach a bilateral ceasefire deal.

That the talks have got this far demonstrates the desire for peace on both sides, but delays in granting amnesties to detained rebels is threatening to derail negotiations.

Wide ranging rebel-proposed social and economic reforms, which the CPP has described as the core of the talks, are also still to be agreed.

- Published8 October 2012

- Published27 October 2015

- Published17 February 2016

- Published15 January 2017