Japan gets first sumo champion in 19 years

- Published

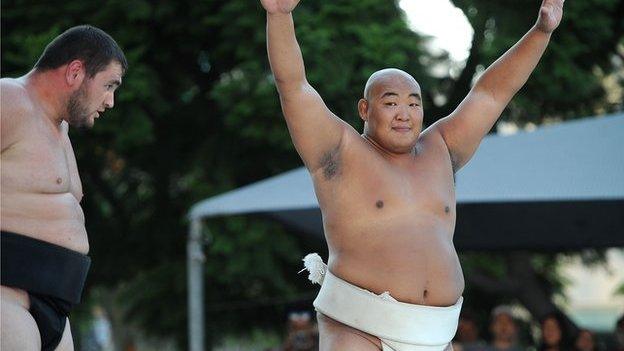

Kisenosato posed for photos with a red sea bream, a traditional way to mark victory

Japan has formally named its first home-grown sumo grand champion in almost two decades, in a boost to the traditional wrestling sport.

Kisenosato, 30, was promoted to the top-most yokozuna rank after his win in the first tournament of the year.

He is the first Japanese-born wrestler to make it since Wakanohana in 1998. Five wrestlers from American Samoa and Mongolia have made it in the interim.

Foreign wrestlers have come to dominate sumo, amid a lack of local recruits.

Kisenosato, who comes from Ibaraki to the north of Tokyo and weighs 178kg (392 pounds), has been an ozeki - the second-highest rank - since 2012.

After being runner-up on multiple occasions, he finally clinched his first tournament victory - and thereby his promotion to yokozuna - in the first competition of 2017.

"I accept with all humility," Kisenosato said in a press conference after the Japan Sumo Association formally approved him.

"I will devote myself to the role and try not to disgrace the title of yokozuna."

What is sumo?

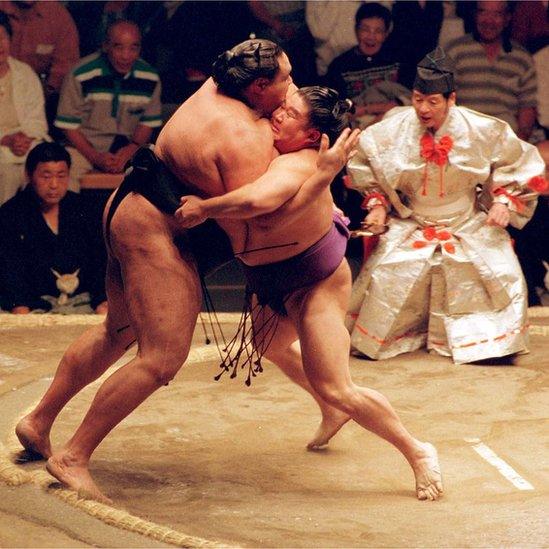

Wakanohana (R), seen here fighting Hawaiian Akebono, was the last Japanese wrestler to be promoted to yokozuna

Japan's much-loved traditional sport dates back hundreds of years.

Two wrestlers face off in an elevated circular ring and try to push each other to the ground or out of the ring.

There are six tournaments each year in which each wrestler fights 15 bouts.

Wrestlers, who traditionally go by one fighting name, are ranked and the ultimate goal is to become a yokozuna.

Many Japanese fans will be pleased to see a local wrestler back at the top of a sport regarded as a cultural icon.

As yokuzuna, Kisenosato, whose real name is Yutaka Hagiwara, joins three other wrestlers in sumo's ultimate rank - Hakuho, Harumafuji and Kakuryu.

The trio all come from Mongolia, following a path forged by sumo bad-boy Asashoryu, who was Mongolia's first yokozuna in 2003.

The last Japanese-born wrestlers to reach the top were brothers Takanohana and Wakanohana, who made it to yokozuna in 1994 and 1998 respectively.

In recent years, sumo has been hit by falling numbers of Japanese recruits, partly because it is seen as a tough, highly regimented life.

Young sumo wrestlers train in tightly-knit "stables" where they eat, sleep and practise together and are sometimes subjected to harsh treatment in the belief that it will toughen them up.

In 2009, a leading coach was jailed for six years for ordering wrestlers to beat a young trainee who later died, in a case that shocked the nation.

Those at the top of the sport are also expected to be role models, showing honour and humility - and can be criticised if they get it wrong.

Mongolian wrestler Asashoryu led the sport for many years, but sumo elders were troubled by some of his behaviour

Sumo must also compete with the rising popularity of football and baseball, which have vibrant leagues that draw crowds of young Japanese fans.

But the sport is attractive to wrestlers from other nations, who can earn a good living. Wrestlers have come from Estonia, Bulgaria, Georgia, China, Hawaii and Egypt, as well as Mongolia and American Samoa.

As a child, Kisenosato was a pitcher in his school's baseball club before he chose to train as a wrestler at a stable in Tokyo.

He made his debut in 2002 and, reported Japan's Mainichi newspaper, the 73 tournaments he took to become a yokozuna are the most by any wrestler since 1926.

Speaking to reporters after the tournament victory on Monday that sealed his elevation, Kisenosato said he was pleased to be holding the Emperor's Cup trophy at last.

"I've finally got my hands on it and the sense of pleasure hasn't changed," he said. "It's hard to put into words but it has a nice weight to it."

- Published4 April 2015

- Published29 September 2014