Tanna: The Oscar-worthy film inspired by a Vanuatu tribal song

- Published

Tanna was inspired by a real-life incident that threatened the peace on the island

It's a tale of love and tragedy which some have called a Vanuatu version of Romeo and Juliet. But Tanna, which this week was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, is no ordinary story about star-crossed lovers.

Made by Australian filmmakers Bentley Dean and Martin Butler, the film is based on an actual incident which roiled the island of Tanna in Vanuatu, which it is named after (spoilers ahead).

Tanna is known more for its tourist attractions such as an active volcano, picturesque jungles and beaches, and Prince Philip cults, external.

But it also has a rich tribal culture, governed by a rigid set of beliefs known as kastom, in which inter-tribal arranged marriages play a crucial role in maintaining social stability.

In the 1980s, a young couple from two different tribes had fallen in love and wanted to marry. But their tribes were vehemently against it. The lovers eventually killed themselves, an act which profoundly shook the community.

"(There was the sense of) 'How could you kill yourself?' There had been no precedent, of people committing suicide for love," Mr Dean tells the BBC.

"So a song came from that. Someone said he received it from their spirits. It's sung in first person, and says, you saw how much we loved each other but refused to let us be together, now we have to say goodbye." It is still sung to this day.

After several similar suicides by those who had not been allowed to marry, the people of Tanna were forced to allow love marriages, and they now make up about half of tribal nuptials.

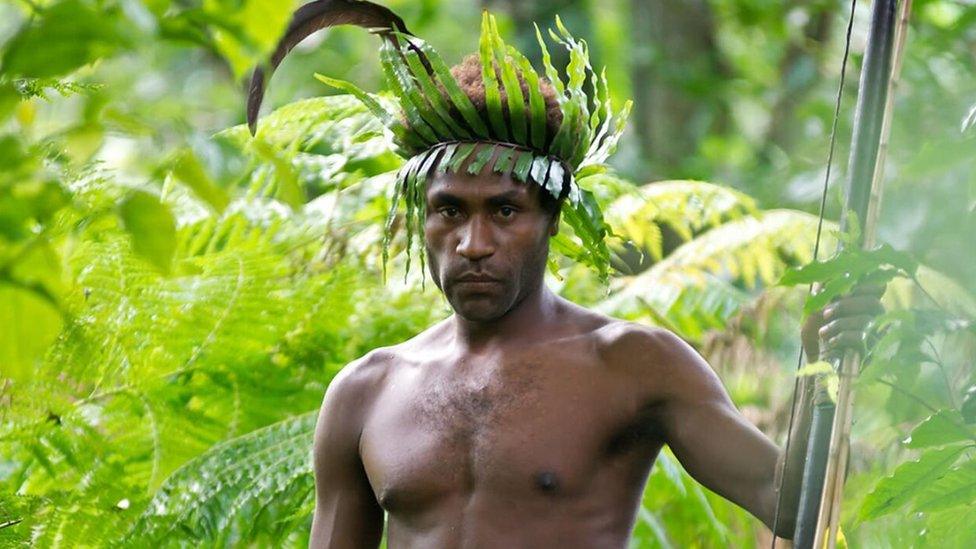

The movie Tanna stars Yakel tribespeople Marie Wawa and Mungau Dain

Acid rain and threat of war

Mr Dean was first inspired by Tanna when he visited the island ten years ago with Mr Butler to make a news documentary. Eventually, with the help of Vanuatu's cultural authorities, he made contact with the Yakel tribe who agreed to host him.

Mr Dean, his wife and two young sons lived with them for seven months in 2014, while Mr Butler flew in periodically from Australia to make the film. JJ Nako, a Tanna local, acted as their translator and cultural interpreter.

The filmmakers arrived without a plot and script, hoping to collaborate with the people of the tribe to tell a story - which they found once they heard of the tribal song.

"(The Yakel) thought it was a story they wanted to tell, it's one that they're intimately involved in. And the important thing they wanted to show was the strength of their kastom," says Mr Dean.

The film shows the Yakel tribe going about their daily lives as well as enacting customs

The movie was made with a skeleton film crew using minimal equipment - Mr Dean was the cinematographer, Mr Butler did sound, and Mr Dean's wife Janita managed the production together with villagers, while doubling up as the make-up artist. "She had a hard time of it, slathering coconut oil on ripped male bodies," jokes Mr Dean.

There was no electricity, so they had to bring in solar panels to charge their equipment, and used natural light to film.

The movie's entire cast is made up of non-professional actors - all of them are tribespeople. In fact, none of them had actually watched a movie before the filmmakers arrived.

Casting was initially straightforward - they cast members of the Yakel, with the chief and medicine man playing the same roles in the film. Their lead actor, Mungau Dain, was chosen by the tribe as he was deemed their most handsome man.

Mr Butler (second from left) and Mr Dean (second from right) made the film in 2014 with the Yakel tribe

Mungau Dain was chosen to be the lead actor as he was deemed their most handsome man

But they got into a pickle when looking for actors to play a rival tribe in the film. The Yakel decided to approach a real-life rival tribe, who promptly refused and insulted them.

This quickly escalated into a conflict with the prospect of a tribal war, until the filmmakers made amends by giving a pig and exchanging kava - a highly prized drink used in ceremonies and rituals - with the rival tribe as a peace offering. A friendlier tribe was eventually cast.

There was also the challenge of keeping equipment clean in a humid jungle constantly blanketed by volcanic dust, with Mr Dean having to battle acid rain while filming on Tanna's volcano.

The film has been praised for its stunning visuals of Tanna island

The volcano Yasur is featured prominently in the movie

Even the film's premiere at the village came under threat when Cyclone Pam hit Vanuatu just as the filmmakers were about to board a plane from Sydney.

"They said that we still had to come... It looked like a bomb had gone off, the destruction was incredible. Only about a third of the huts were rebuilt, but everyone was still in good spirits," he said.

The villagers made a screen out of two queen-size bedsheets tied to a banyan trees, and dozens of tribespeople came from all over Tanna to watch it - including the rival tribe, whom the Yakel eventually made peace with.

"For many it was their first moviegoing experience, and it was a film in their own language, Nauvhal," he said.

The tribe set up a makeshift screen for the film premiere, weeks after Cyclone Pam hit in 2015

'Making a more loving society'

But making Tanna has also raised certain ethical questions.

One was ensuring the filmmakers did not cause fundamental change to the tribe's lives, which arose when they discussed compensation.

The Yakel have a cashless society, and the filmmakers wanted to pay in pigs and kava, but the villagers asked for money.

"We were concerned that it would change them, but it was paternalistic of us.... They eventually took us aside and said, you know we use money (with the outside world)," says Mr Dean.

People from the tribe occasionally visit the nearest town's market - about a two hour walk away - to buy pigs or other essentials. Some even use mobile phones now.

The filmmakers eventually paid them a "substantial amount", which was used to fund a traditional circumcision ceremony for families in the surrounding area. "You could say 26 foreskins were sacrificed in the making of this film," jokes Mr Dean.

Another issue was exposure to the outside world - the filmmakers discussed with the tribe the possibility that the film would attract more tourists to the area.

"Their response was they want people to come and see how they do things, they are extremely proud of their culture," says Mr Dean. If the influx became too large, they would close off the road that leads to their mountaintop village, the Yakel told him.

Members of the Yakel tribe have travelled to Australia, Los Angeles and Venice for film festivals

The Tanna tribes, says Mr Dean, form "a community that has made the deliberate decision to live traditionally".

"They're aware of the outside world. They're fascinated. But they always want to come home, they feel it's the best life for them. The social harmony is extraordinary.

They're very savvy and aware of what could be good and might be bad for their culture, they are constantly thinking about these things."

But Tanna, the film, also aims to show that these societies are not always closed-off and rigid.

"There's a tendency to view traditional tribal societies as locked in time, but the truth is different - they are constantly changing, constantly evolving.

"And these guys made a very important decision, which is to make a new reality and a more loving society."