Koh Nguang How: Singapore's one-man museum

- Published

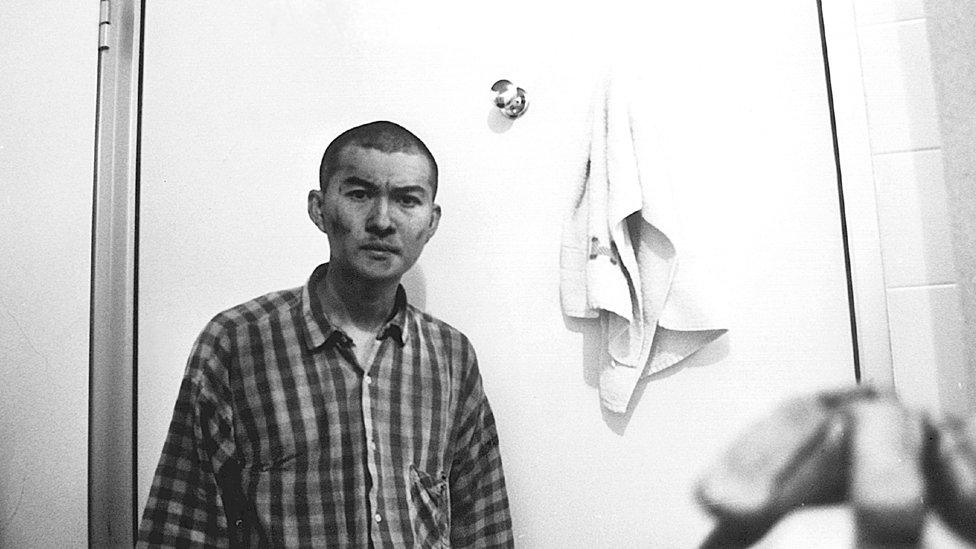

Mr Koh, seen here in an undated picture from his youth, has collected nearly one million pieces of cultural value

In a small council flat in Singapore lies one of the South East Asia's richest collections of cultural artefacts. Journalist and historian Prof Scott Michael Anthony explores this unique one-man museum and the story behind it.

Before every Chinese New Year, Koh Nguang How spends several weeks clearing his mother's flat.

The 54-year-old is a hoarder, and his collection of more than one million items fills up his flat, his parent's flat, and a space rented at a nearby industrial unit.

Everywhere you look, Mr Koh is surrounded by epic piles of newspapers, flattened posters and boxes overflowing with tapes.

"Without looking at it carefully it could be mistaken for the junk collected by my neighbours every Friday morning," he admits.

An 'impulse to archive'

Nothing could be further from the truth. In a space about the size of a double garage, Koh has amassed an extraordinary collection of photographs, papers and recordings charting the development of the cultural scene in South East Asia.

In a region until recently notorious for its lack of interest in collecting and curating cultural objects, his flat in the northern suburb of Yishun has quietly become the single most important location in the country's popular cultural heritage.

Mr Koh houses his artefacts in boxes and folders in his flat, which his niece (pictured) sometimes goes through

"Unlike America or Europe, there hasn't really been an impulse to archive in the region," explains Nora Taylor, a professor of South and South East Asian Art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

"Part of the reason is materials are scarcer and they don't last as long in the climate, or political regimes have changed, or they're reminiscent of colonial impulses."

Mr Koh's story began when he joined the National Museum of Singapore as a museum assistant in 1985.

At the time the museum only had a small staff, and the business of preparing and marketing exhibitions led him to begin collecting posters, catalogues and all kinds of visual ephemera.

He took pictures and, lacking the money for a video camera, tape-recorded performances.

"The national archives were really just a record of the government," says Mr Koh. "It tended to be a record of what politicians said at an event, not the event itself."

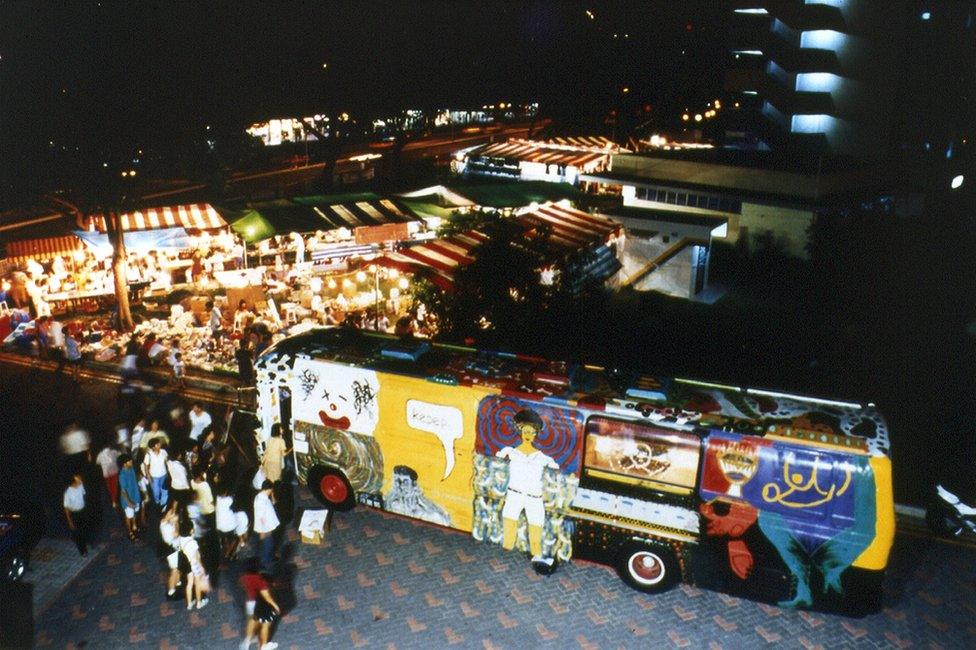

Mr Koh documented the Art Bus, a mobile art exhibition that toured the island in 1996

Mr Koh periodically displays his artefacts in public exhibitions, such as this one in 2014

This was a point in time where the Singapore government was almost exclusively focused on industrial development, and the museum stood alone as a place for artists and musicians of all generations to mix. His collecting began to fill the gaps in the official record.

"Working at the museum was my university," remembers Mr Koh. "At the time, aside from architecture, it wasn't even really possible to study the arts at university in Singapore."

Dealing with visiting exhibitions sponsored by organisations such as the Goethe-Institut and the Institut Français served as a personal primer in aspects of 20th Century culture.

Mr Koh's flat with its box files, storage bins and stacked papers illustrate the practical importance of his apprenticeship. When he left the national institution, he turned into a one-man museum.

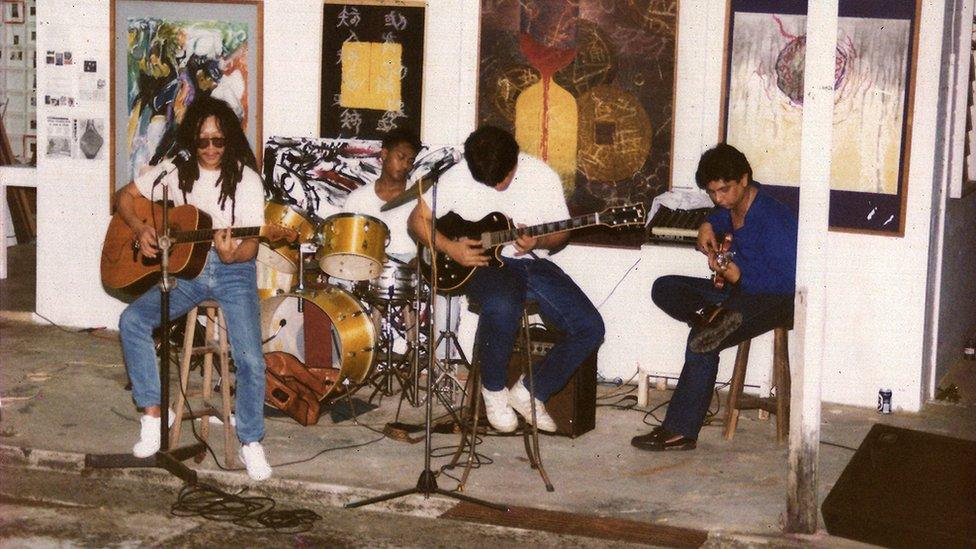

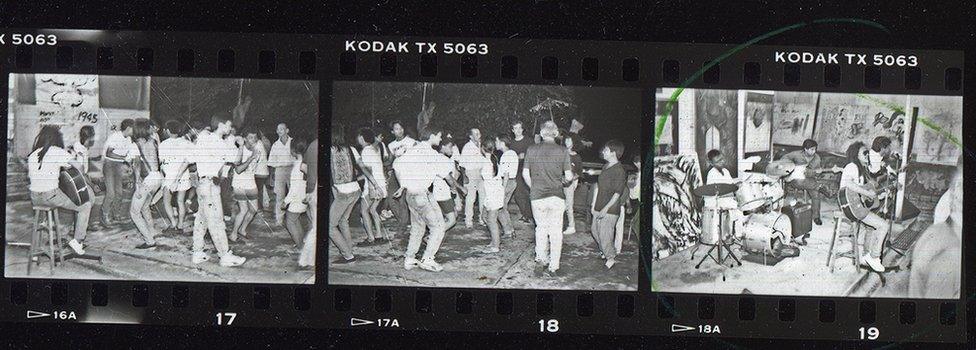

Among Mr Koh's many artefacts is a picture of Singapore's first reggae band Igta, playing in the 1980s

Mr Koh documented one of their first gigs

Over time the archive evolved from being a collection of Mr Koh's enthusiasms into a record of art education in the region.

When the Singapore government began to invest in culture during the 1990s, Mr Koh's archive became an essential resource for providing information about the place, time and production of now iconic paintings such as, Chua Mia Tee's National Language Class., external

The work of artists like Chua Mia Tee had been important in the struggle for Singapore's independence, but fell sharply out of cultural and political favour shortly afterwards.

Mr Koh's archive helped recover the careers of the social realists, such as the Equator Arts Society that Chua Mia Tee was associated with, to the extent that their work features prominently in Singapore's formidable new National Gallery.

Artist Chua Mia Tee (right) is seen here with his iconic painting National Language Class at the National Gallery together with Singapore prime minister Lee Hsien Loong (left)

"When I first went to see him, I was treating his archive as a source of information," remembers Prof Taylor. "But as people came to talk to him, I realised that he's really tied to the documents and what they trigger. In my mind he became a story teller, a performance artist doing this performance of history."

Mr Koh's archive is not just a record of a scarcely remembered cultural life, but also a record of disappearing ways of life.

The ultra-rapid transformation of Singapore in the later decades of the 20th Century meant that even walking to work could become a disorientating experience.

"In Singapore we don't have natural disasters," he says. "But we do live with the trauma of constant demolition."

Singapore has seen profound changes to its cityscape in the last few decades

Taking inspiration from the work of British land artists such as Hamish Fulton, Mr Koh began to photograph the frenetic development of the urban landscape. It was a response to the sense of emotional dislocation that accompanied the city's transformation.

Even Mr Koh's archives have lived a peripatetic life. "My late dad used to be an air-cargo truck driver and he was a good driver for my archives," he remembers.

His archive was built partly by applying the techniques of a land artist to a place where there is almost no land.

"He's an enthusiast and a bit of an obsessive," says Tamares Goh, artist and former head of visual arts at The Esplanade arts centre. "So it's not just what he's collected that is significant, but the spirit which he has collected it in."

"People are curious and appreciative of Koh's work," she says. "But alongside the nostalgia there is surprise at this record of a very impromptu and organic world that no longer exists."

Since Mr Koh left the Museum in 1993 his archive has become a respected artwork in its own right.

In 2014, his Singapore Art Project installation at the Centre for Contemporary Art used his collection to tell the story of art in the region from the 1920s to the internet age.

Many of his artefacts were displayed in a 2014 exhibition at Singapore's Centre for Contemporary Art

He has also created an entire series of popular exhibitions entitled Errata, that used his archive to illustrate mistakes in existing histories and encourage visitors to actively verify official records.

Elements of his archive have also been exhibited in Cambodia, Japan and South Korea, as well as in Europe and beyond, as researchers use Mr Koh's photographs, itineraries and newspapers to piece together obliterated histories.

There's something pleasingly contemporary about this - a personal archive as inoculation against fake news and wiped memories.

'Infinite library'

This success has also changed the family's perception of Koh. "My own flat is usually filled with my archives," explains Mr Koh. "And yes my family members did feel that I was crazy."

Now aspects of his personal archive have been exhibited internationally, as well as at the Gillman Barracks arts hub in Singapore, the mood has shifted.

"It also helped to change their perceptions of my archives and projects that the National Gallery Singapore had wanted to procure part of my collection," he says.

Mr Koh lives in the quiet housing estate of Yishun

The Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote a short story about a library that contains a universe of books made up of every arrangement of 25 letters possible, and therefore every book that can ever be written as well as an infinite number of variations on them.

With material stretching from reggae to woodcuts, to performance art, dance and theatre, one can feel similarly overwhelmed by Mr Koh's range.

But his ambition remains modest. Koh simply hopes to turn his flat into a space where his collection can be consulted by anyone.

Yishun once made the local news for being home to the first neighbourhood in Singapore where it was permitted to keep cats. Now the unobtrusive suburb plays host to a unique cultural ark - a tiny version of Borges' infinite library that can be tidied away for Chinese New Year.