IS in Afghanistan: How successful has the group been?

- Published

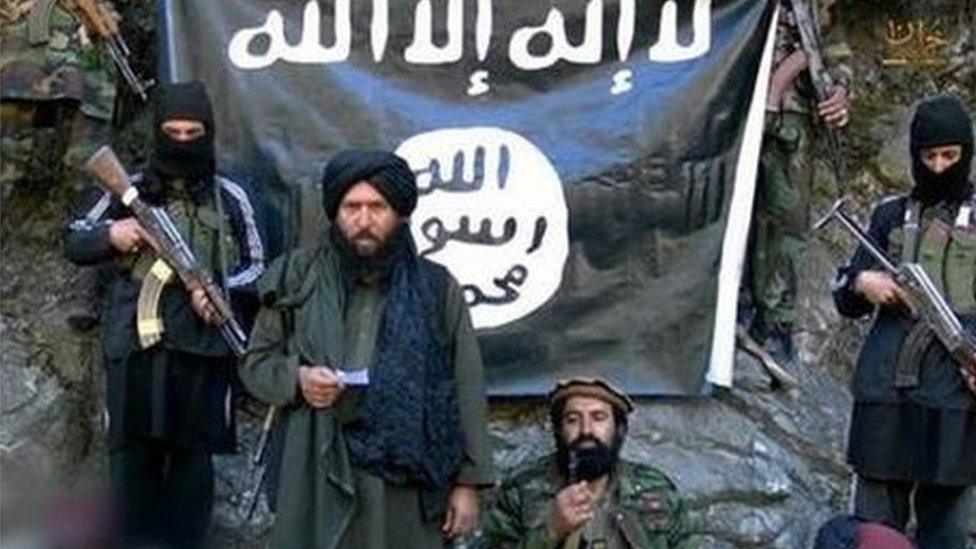

IS's Afghanistan chief Hafiz Saeed Khan was killed in a US air strike in July last year

Amid a rise in attacks in Afghanistan attributed to the so-called Islamic State (IS), the BBC's Dawood Azami examines what kind of threat the militant group poses in the conflict-hit nation and the wider region.

How much territory has IS captured?

IS announced the establishment of its Khorasan branch - an old name for Afghanistan and surrounding areas - in January 2015. It was the first time that IS had officially spread outside the Arab world.

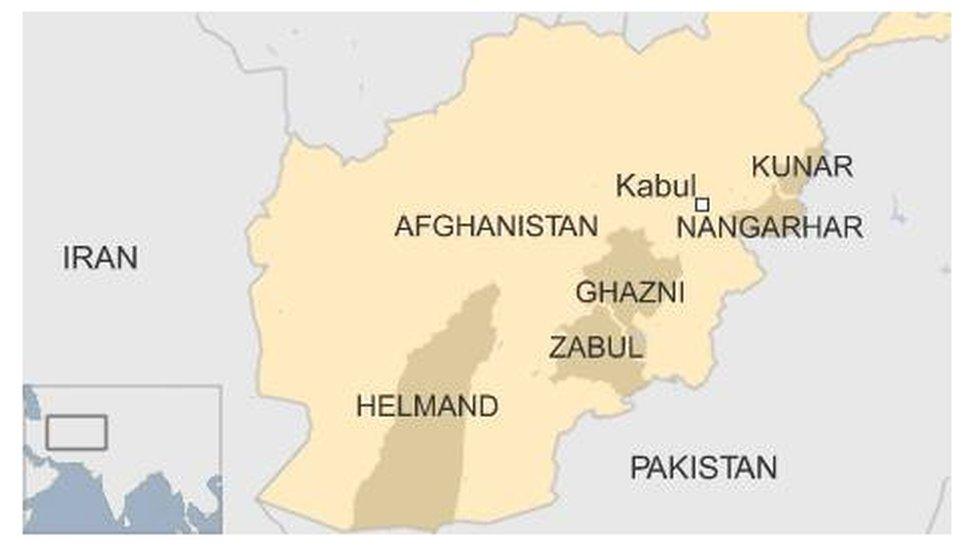

Within a few weeks, the group appeared in at least five Afghan provinces, including Helmand, Zabul, Farah, Logar and Nangarhar, trying to establish pockets of territory from which to expand.

It was the first major militant group to directly challenge the Afghan Taliban's dominance over the local insurgency. Its first aim was to drive Afghan Taliban fighters out of the area and it also hoped to evict Taliban ally al-Qaeda from the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, or absorb its fighters.

Yet despite efforts to energise battle-weary militants, IS struggled to build a wide political base and the indigenous support it expected in Afghanistan. Instead, it made enemies of almost everyone, including the Afghan Taliban.

In the first half of 2015, IS managed to capture large chunks of territory in eastern Nangarhar province. This became the de facto "capital" principally for two reasons - its proximity to the tribal areas of Pakistan, home of IS Khorasan's top leaders, and the presence of some people who follow a similar Salafi/Wahhabi interpretation of Islam to IS.

IS is also trying to get a foothold in northern Afghanistan, where it aims to link up with Central Asian, Chechen and Chinese Uighur militants.

But it has largely been eliminated from southern and western Afghanistan by the Afghan Taliban and military operations conducted by Afghan and US/Nato forces.

Six Red Cross workers were killed earlier this month in northern Afghanistan by suspected IS militants

It has also lost territory in eastern Afghanistan in recent months. But it still has control over some parts of Nangarhar and Kunar provinces, where it plans attacks and trains fighters.

Small IS pockets have also been reported in Zabul and Ghazni, as well as a few northern provinces.

How many fighters does IS have?

Since its emergence in Afghanistan, IS has lost hundreds of militants in US air strikes and ground fighting with the Afghan military. Meanwhile, several hundred IS fighters have been killed in clashes with the Afghan Taliban.

Around a dozen top leaders of the group's Afghanistan-Pakistan branch, including founding leader Hafiz Saeed Khan, a former Pakistani Taliban commander, and his deputies, have been killed in Afghanistan, mostly in US drone attacks.

Estimates about IS's numerical strength inside Afghanistan vary, ranging from 1,000 to 5,000.

US General John Nicholson, the top commander of US and Nato troops in Afghanistan, estimates that between 1,000 and 1,500 IS fighters are in Afghanistan. He says their number has been cut in half, from an estimated 3,000, by military operations over the past year or so.

Afghan security forces have been battling IS fighters, but the group has survived the onslaught

He adds that about 70% of those fighters come from the Pakistani Taliban group (TTP), some of whom moved to Afghanistan after the Pakistani military launched an operation in North Waziristan tribal area in 2014. But Afghan security officials insist that 80% of IS militants are Pakistanis.

The other members were part of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), a group focused on Central Asian countries, and former Afghan Taliban or new recruits, they say.

IS has so far survived the onslaught and it seems the group is attracting new recruits to replace those killed.

What are its tactics?

After losing territory, IS Khorasan is emulating its Middle East counterparts by resorting to guerrilla tactics such as suicide attacks, targeted killings and the use of IEDs.

It says it carried out some of the deadliest recent attacks in Afghanistan, several of them in the capital, Kabul.

In July 2016, a suicide bomb attack on a rally in Kabul killed about 80 people. Three months later, two similar attacks during the religious festival of Ashura claimed around 30 lives and in November 2016 an attack at a mosque in Kabul killed more than 30. All of these attacks targeted minority Shia Muslims.

IS has also claimed responsibility for attacks in other parts of the country and has killed civilians, including tribal elders and religious scholars opposed to its extreme ideology and brutal tactics.

Nato estimates that there are between 1,000 and 1,500 IS fighters in Afghanistan

Like its counterparts in the Middle East, IS Khorasan has taken violence to new levels, even by the bloody standards of the region. While al-Qaeda introduced suicide bombings into the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, IS brought new and more ruthless tactics.

In one notorious example an IS video released in August 2015 showed 10 blindfolded community elders in Achin district in Nangarhar being forced to sit on holes in the ground filled with explosives. They were then blown to pieces.

Beheadings and abductions, including of women and children, are other tactics.

In addition, IS propaganda on the internet and air waves is strong. The group has several Twitter and Facebook accounts and has been broadcasting on an FM radio station in Nangarhar since December 2015.

Radio Caliphate can be heard in Nangarhar and Kunar provinces, as well as adjacent parts of Pakistan. The station was once hit in a US airstrike but was back on air within a few weeks.

Why does IS attack Shias?

IS has also carried out attacks in Pakistan, where it relies mainly on the support of certain anti-Shia sectarian groups. The first major attack in Pakistan for which IS claimed responsibility was in May 2015 when about 40 minority Shias were killed in a gun attack on a bus in the country's biggest city, Karachi.

On 16 February, IS said it carried out an attack on the Lal Shahbaz Qalandar Sufi shrine in the town of Sehwan in Sindh province. Police say 90 people were killed.

The attack at the Lal Shahbaz Qalandar Sufi shrine shocked Pakistan

The conflict in Afghanistan has been going on for nearly four decades, but the country has largely remained immune to the sectarian violence that has hit other regional nations.

IS, however, aims to turn the conflict in Afghanistan into a sectarian war between the majority Sunnis and minority Shias, as it has tried in Syria and Iraq. Shias are considered apostates by IS, which follows an austere version of Sunni Islam.

Read more

Although IS has also killed many of its Sunni opponents, it has clearly stated sectarian goals in a number of its attacks.

Justifying the July 2016 attack on the Shia rally in Kabul, IS called it retaliation for the activities of Afghan Shia Hazaras who have gone to Syria via Iran to fight for the government of President Bashar al-Assad, an Alawi-Shia, against the Islamic State group.

Deliberate attacks by IS against Shia in Afghanistan add a dangerous complication to the conflict.

How do regional powers view IS?

The future of IS in Afghanistan and Pakistan is in many ways linked to the fate of IS in Syria and Iraq.

Western and Afghan military officials confirm the group has financial ties to, and is in communication with, the main IS leadership. It also has contacts with IS cells operating in South and Central Asian countries.

So far, IS has not been able to carry out attacks outside Afghanistan and Pakistan. But the group has many sympathisers in the region.

Additionally, thousands of volunteers from nine South and Central Asian states - Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan - have gone to Syria and Iraq to fight for IS.

They have been trained and radicalised there. The return of these militants will pose a new threat and might strengthen the existing IS infrastructure in the region.

Such developments further complicate the conflict in Afghanistan and pose a long term risk to regional stability.

Regional powers, such as Russia, China and Iran, are concerned about the threat that IS poses to their internal security. These powers have established contacts with the Afghan Taliban, which is fighting IS, to hedge against the potential risk.

Mutual mistrust is preventing regional players from reaching a consensus to end the conflict in Afghanistan.

- Published8 February 2017

- Published17 February 2017

- Published18 December 2015

- Published6 February 2017

- Published12 January 2015

- Published12 January 2017

- Published17 October 2017