Malaysia and North Korea - a friendship on ice

- Published

North Korea's Malaysian embassy is under scrutiny as never before

North Korea and Malaysia have taken the extraordinary step of banning each other's citizens from leaving their countries in the fallout over the killing of Kim Jong-nam. Security expert Hoo Chiew-ping traces the history of this unusual relationship.

Malaysia is not alone in sharing what some have called a "special relationship" with North Korea. In fact, many other South East Asian nations have developed close ties with the reclusive and rogue state.

But their history begins in conflict and dates back to the 1950s when Malaya - as it was known then - was fighting a communist insurgency while North Korea provided training assistance to local communists.

The Malayan Federation then gained independence from Britain, and in the early part of the Cold War the new nation adopted the anti-Communist rhetoric of the time. But after the US detente with China, Malaysia became the first South East Asian state to establish diplomatic ties with China.

Kim Jong-nam spent time in both Singapore and Malaysia, both of which were friendlier to North Korea than others

What is interesting are the events prior to that. Malaysia established diplomatic ties with North Korea on 2 July 1973, well ahead of the establishment of relations with China in May 1974.

It remains unclear exactly why Malaysia would go down such a path. The main reason could have been a desire to embrace neutrality as Malaysia's new strategic foreign policy direction.

And indeed Malaysia's pole position with the North allowed it to play a friendly third nation role in facilitating secret talks as well as open negotiations between the US, South Korea and North Korea throughout the nuclear talks in the 2000s.

North Korean Ri Jong Chol, initially a suspect in Mr Kim killing, worked in Malaysia for years

Business ties also served as a cornerstone of a special relationship that spanned from tourism, the mutual visa-waiver programme, to a special chartered direct flight between the capitals that other states don't normally enjoy.

A relatively large cohort of North Korean workers can also be found working in the state of Sarawak. The state government there has jurisdiction over labour import matters, independent of federal government, but in order to be able to reach a deal on importing North Korean labour it would have to have received federal approval.

The benefits to the North Korean regime are obvious, bringing it hard cash while the workers receive meagre pay for their labour.

But what does Malaysia get out of the entire package?

Well, there is a trade in raw materials, which North Korea is famous for, and the export of Malaysian processed food for the consumption of Pyongyang elites, department stores and resident foreigners, as well as palm oil.

In truth, the deals were likely small in scale, but symbolic for that burgeoning "special relationship" between Malaysia and North Korea.

But it was really Malaysia as an outpost for illegal North Korean economic activities that allowed it to have such cordial relations with the pariah state. One example of such activity was the instruction from the US Treasury to close down a North Korean bank account in a local Malaysian bank that was allegedly used for weapons deals with Myanmar, back in 2009.

Air Koryo's ageing fleet is banned in many places, but Malaysia, like China (depicted) was happy to have it land

It is also widely believed that North Korea's Air Koryo serves those cities where it can directly bring back hard cash for the North Korean regime. All trade is important for North Korea and the regime survives on foreign financial dealings, whether they are legal or illegal economic activities.

The Malaysian government's position prior to this point appears to have been one of silent neutrality. Officials deny endorsing the violation of any sanctions, and so any support from elements in Malaysia has always been discreet. The international repercussions would be severe if any evidence of a role in facilitating illegal activities were to surface.

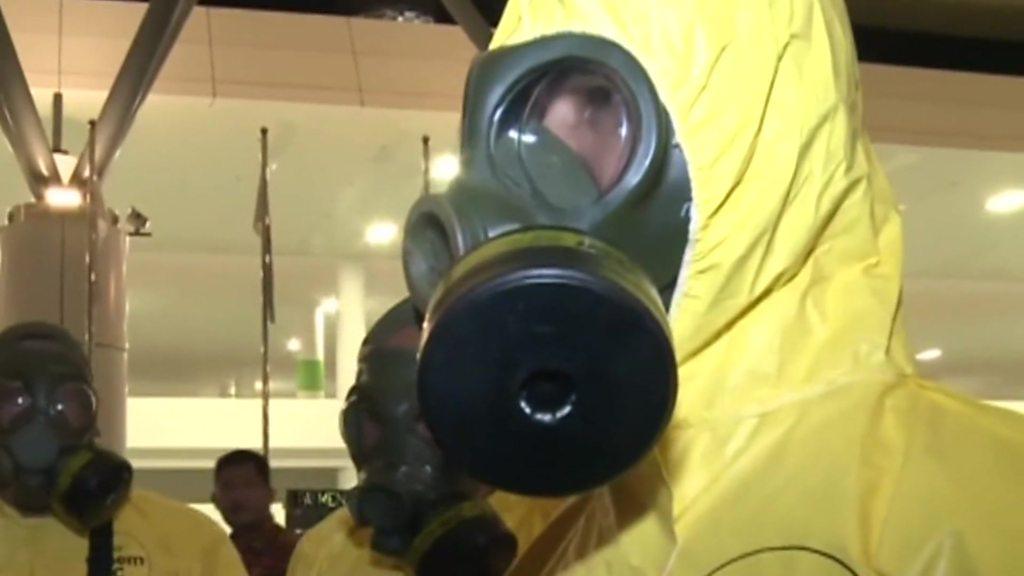

But everything changed with the killing of Kim Jong-nam in a Kuala Lumpur airport using a deadly nerve agent. It has seen Malaysia take firm and swift action to alienate North Korea.

The hardline position of Najib Razak's administration is a departure from Malaysia's traditional diplomatic behaviour, which normally seeks to de-escalate conflict.

Pyongyang shows no sign of handing over North Korean suspects in Mr Kim's death

But in fact a number of countries in South East Asia have had a special relationship in some way or another with North Korea - including Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The regional Asean grouping reached a kind of consensus that it would not utterly isolate Pyongyang and would instead play the role of engaging North Korea in order to ensure regional stability and not suffer the spill-over effects of any North Korean provocations.

North Korea is a member of one of Asean's bodies, the Asean Regional Forum (ARF), which has proved to be a useful mechanism to regulate its relationship with the region. It even used to send its top diplomat to the ARF meetings.

But when in July 2016, ARF expressed concerns over North Korea's nuclear programme, Pyongyang tried in vain to request ARF to revise the statement. Its failure to do this may have driven North Korea away further from some friends in South East Asia.

But the Najib government's move also plainly shows that Malaysia has decided to distance itself from North Korea, if not quite cutting it off altogether.

The airport killing has strained relations with more countries than just Malaysia

Now that Malaysia has fallen off the North's friends list, it is likely to look towards emerging states like Myanmar to provide it with what it needs.

But the one constant throughout all these painful and discreet diplomatic manoeuvres is the unpredictability of Pyongyang.

Dr Hoo Chiew-Ping is a Senior Lecturer in Strategic Studies and International Relations at the National University of Malaysia.

- Published7 March 2017

- Published3 March 2017

- Published15 February 2017

- Published1 March 2017

- Published26 February 2017

- Published27 February 2017

- Published25 February 2017

- Published24 February 2017

- Published2 October 2017