How fake news and hoaxes have tried to derail Jakarta's election

- Published

An illustration by comic artist Komikazer showing the convergence of Jakarta's local election and social media is hate

In Indonesia, the rise of fake news, hoaxes, and misleading information online has cast a pall over an already bitterly divided election in the capital, Jakarta. BBC Indonesian's Christine Franciska looks at why activists are describing this as a dark era in Indonesia's digital life.

It is impossible to explain Jakarta's election without first introducing Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, or Ahok, who stepped up in 2014 when then-governor Joko Widodo became president.

Mr Purnama is the first Christian and ethnic Chinese leader of the Muslim-majority city in more than 50 years, and now is running for another term.

He was seen as the favourite to win - and for some, as a potential future president - until he was charged with blasphemy in late 2016, a criminal offence in Indonesia.

Despite mass protests against him, Mr Purnama led the election's first round in February but without enough votes to secure the job outright, so a second round will be held on 19 April.

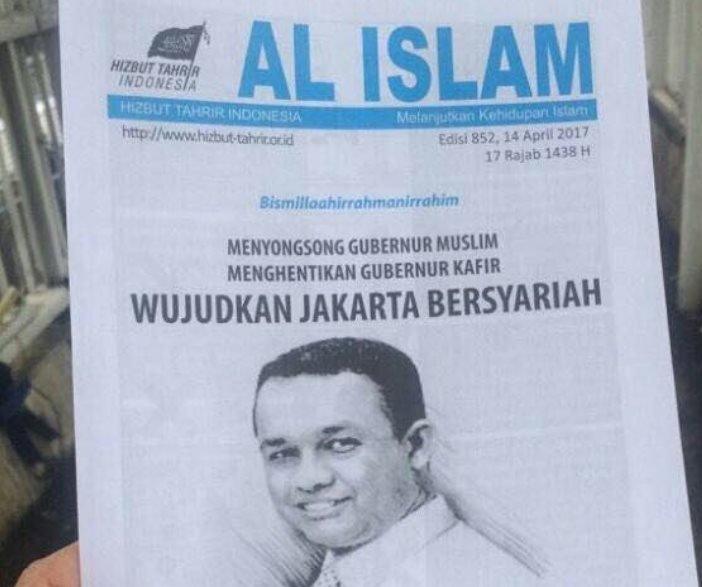

His opponent is a former education minister and Islamic conservative Anies Rasyid Baswedan, who has gone from being the most unpopular candidate to the strongest contender, according to recent polls.

The blasphemy case testing Indonesia's very identity

It is an election divided not just by politics but by religion too and of all things, hoaxes have put a potent edge on these tensions.

"We recorded that there are more than 1,900 alleged-hoax reports in recent three months," said Khairul Ashar, a co-founder of Turn Back Hoax, external - a crowd-sourced digital initiative where they collected and debunked hoaxes spreading in social media.

"More than 1,000 reports have been confirmed as hoaxes. Most of these are about politics, mainly about Jakarta's gubernatorial election. And religious issues play a big role," said Mr Ashar, who lives in Singapore.

Alternative facts

Mr Purnama (right) and President Joko Widodo (left) welcomed King Salman in Jakarta, early March.

The recent visit of Saudi Arabia's king is one of the examples of how the truth was reversed in the online imagination. This picture of Mr Purnama shaking hands with King Salman when he arrived in Jakarta early March was condemned as false on social media even though it was captured by the Indonesian president's official photographer.

King Salman is widely praised in Indonesia as an Islamic role model, so this photo would be seen as a great boost for Mr Purnama.

But groups opposed to him said, "This news is hoax, because it is haram for a king to shake hands with the blasphemer of Islam." One Facebook user even posted a long analysis explaining how it was a fake story.

Some did retaliate: "You have (official) picture, and also an (official) video (of them shaking hands), but still people thought it was fake. Your life is a hoax."

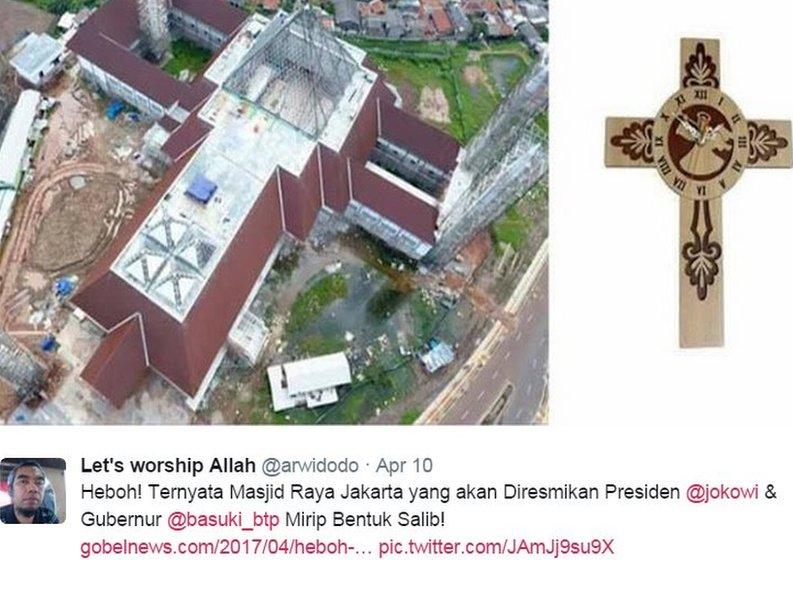

Recently, President Joko Widodo inaugurated the first city-owned grand mosque in Jakarta, but some people argued it looked like a cross, and then proceeded to accuse Mr Purnama of "Christianisation".

The first city-owned grand mosque was open recently in Jakarta but some people argue it looks similar like a cross.

Mr Purnama's opponent has also been smeared by hoaxes and launched an anti-hoax website to counter it called fitnahlagi.com (which translates as defamed again).

There were also fake posters spread online saying: "If Mr Baswedan loses the election, there will be Muslim Revolution" with provocative pictures of men wearing white clothes and holding swords. , external

Fake news attacked Anies Baswedan as well

'The dark age'

This is a big concern for IT activists. "We must change our campaign narrative now," said Matahari Timoer, one of the members of Jakarta-based Internet watchdog ICT Watch.

"It used to be 'think before share', but now we urge people to 'do your part'."

He was talking about their campaign battling the danger of hoaxes and he says there is an urgent need for the "silent majority to speak up and raise their voice on social media."

"Our digital life has entered a dark age, that is why we need people to do their part as a lantern to light up, and fight this dark period," he said.

Matahari Timoer in a documentary 'Lentera Maya' by ICT Watch as an effort to teach digital literacy in Indonesia.

As a former member of a Muslim radical group he understands what's at stake - a rising religious intolerance dividing a nation.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo even declared a war against "fake news" late last year.

There are more than 40,000 websites claiming to be news sites, but most of them are not registered, said the Press Council, who has launched an online media verification system to filter fake news.

Recently, the communications and information ministry urged Twitter and Facebook to combat hoaxes on their own platform. But many believe those efforts are not enough.

Mr Timoer underlined what people called dark social media: WhatsApp groups and Telegram's secret groups, more intimate and influential.

So could fake news really influence the final round of Jakarta's election?

The race to become the governor of Jakarta is one of the most bitterly contested polls in recent years

"It will affect emotional voters. They persist with what they choose based on information related to religion and ethnicity," said Mr Timoer. But he thinks it will only have a small impact in the end.

Mr Ashar thinks differently. He believes the threat behind these hoaxes goes way beyond Jakarta's political battle.

"Some groups want to change philosophical foundation of the country, and in the name of freedom of speech they use hoaxes in social media to gain followers," said Mr Anshar.

All the activists know that even after this election is over, the hoaxes will continue their battle for the hearts and minds of Indonesia's public.

- Published14 February 2017