Park Geun-hye: How identity politics fuelled South Korean scandal

- Published

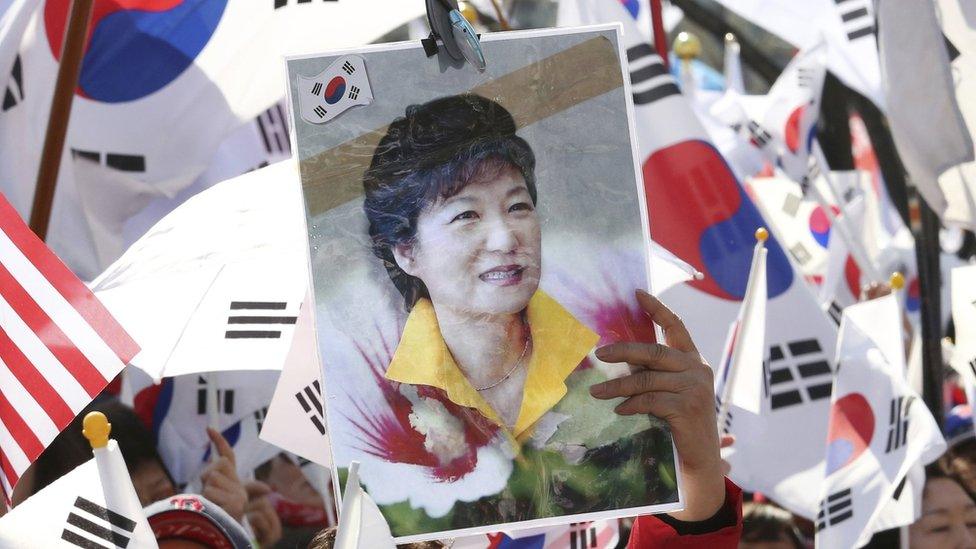

Park Geun-hye's removal by the Constitutional Court follows months of protests by both her opponents and supporters

Like a patient awakened from an enforced period of suspended animation, South Korea's body politic has been sharply brought back to life.

Friday's unanimous eight-person Constitutional Court ruling, that upheld last December's National Assembly decision to impeach President Park Geun-hye, has finally swept away the uncertainty that has paralysed the country for months.

The court's ruling supports 13 counts of impeachment that argued that Ms Park had been unduly influenced by her long-term friend and confidante, Choi Soon-sil, to pressure leading conglomerates to provide some $70m (£57m) of illegal donations to two private foundations managed by Ms Choi.

Viewed narrowly, the case has been about the excessive influence of an unelected and unaccountable private citizen determining government policy, including the appointment of cabinet members, and persuading the president to sanction bribery and influence peddling.

The court's decision strips Ms Park of all political authority, exposes her to the likelihood that she will have to defend herself against criminal charges, and marks the start of a 60-day period that will culminate in the election of a new president in early May.

Viewed broadly, the impeachment controversy reflects deep, historical fissures running through South Korean society.

Read more:

For the 77% of Koreans backing impeachment - including the hundreds of thousands of young and middle-aged voters who joined candle-lit demonstrations over the past months - Ms Park's failings have been proof of the wider institutional and political shortcomings of the country.

This has included: privilege and corruption within the economic elites, underscored by the dramatic arraignment on bribery and embezzlement charges of Samsung Vice-Chairman Lee Jae-yong; favouritism and lack of transparency within an education system that should ideally provide social mobility and success for ordinary Koreans (Ms Choi's daughter was granted unfair access to one of the elite universities); and an authoritarian predisposition on the part of Ms Park to blacklist her political rivals in academia, arts and the media.

Younger voters have rallied against Ms Park, who they see as representative of a privileged elite...

...but many among the older generation back a president whose father built the nation's economic might

For the roughly 20% of the population opposed to impeachment - predominately citizens in their sixties and above - the attack on the president is a politically motivated witch-hunt, based on rumour and unsubstantiated allegations.

At best, according to this view, Ms Park was guilty of poor judgment in relying on her friend, and the court's decision represents a capitulation to populist pressure rather than an informed legal decision.

Identity politics is at the heart of the controversy. To her supporters, the campaign against Ms Park is an attack on the legacy of her father, Park Chung-hee, the authoritarian leader who created the Miracle on the Han River that rapidly transformed South Korea into Asia's fourth-largest economy. Impeaching the president tarnishes and discredits this narrative of success and, by extension, the older generation of Koreans who contributed to the spectacular economic development.

To Ms Park's opponents, the impeachment is confirmation of the renewed vibrancy and effectiveness of political institutions. To them, it is a reaffirmation of the alternative narrative of national development based on the success of the democratisation movement of the 1980s that ended authoritarian rule.

What comes next?

Looking ahead, the key challenge for whoever succeeds Ms Park will be to unify the country and bridge the gap between these two contrasting narratives.

Among a crowded field of some seven to 10 potential candidates, progressive candidates are likely to be best-placed to capitalise on the widespread opposition to the president and the conservative politicians associated with her party.

Moon Jae-in, the former head of the opposition Democratic Party, is the current front-runner, with some 37% support. But he faces a credible primary challenge from his party rival, Ahn Hee-chung, a local governor and charismatic 51-year-old with a reputation for pragmatism and the ability to appeal across the political spectrum.

Mr Moon has been criticized by the more ideologically radical members of his party for excessive caution in responding to the popular campaign against Ms Park. Moreover, his statements in favour of dialogue with North Korea and a pledge to visit Pyongyang have opened him up to the charge of naivety in addressing the current security crisis, at a time when public opinion is increasingly impatient with the North.

Moon Jae-in is the leading candidate to replace Ms Park, but he faces credible rivals

The next president will have little time or resources with which to respond to the immediate challenges. A sharply-truncated presidential transition period means that the new incumbent will likely need to rely on officials from the outgoing administration.

A pro-engagement progressive president is also likely to encounter tensions with a Trump White House that favours a more combative approach towards North Korea and which has rushed to install new Thaad missile defence batteries in the South - a decision fiercely opposed by China. Beijing has been using strong-arm diplomatic pressure and economic discrimination against Korean firms in China to try and reverse the Thaad decision, but already there are signs that this is provoking an anti-Chinese backlash within South Korea.

Foreign and domestic politics will, therefore, be key tests for the next president who will need to respond to the challenge of revitalising a divided and deadlocked polity.

For the now-disgraced former president Park, who entered office in 2013 claiming to govern for all Koreans and who in the 1970s had to adjust to the trauma of seeing both her parents assassinated, the court ruling is surely the definitive end point in a political life marked by tragedy and acute personal disappointment.

Dr John Nilsson-Wright is Senior Lecturer in Japanese Politics and the International Relations of East Asia, University of Cambridge and Senior Research Fellow for Northeast Asia, Asia Program, Chatham House

- Published10 March 2017

- Published9 December 2016

- Published31 October 2016

- Published6 April 2018

- Published6 April 2018