Is Bangladesh winning the war against militants?

- Published

Bangladesh has mounted a series of high-profile raids on Islamist militant hideouts in recent days after the country was stung by a wave of suicide blasts. Many had thought the militants were on the back foot after a security crackdown - so who's got the upper hand?

Early last week, army commandos killed four suspects in a prolonged battle in the north-eastern town of Sylhet. Days later seven to eight people were found blown up as police closed in on them in neighbouring Moulvibazar.

The bloodshed came after three botched suicide bombings in as many days in and around Dhaka, external.

Suicide bombings are rare in Bangladesh - so the apparent shift in militant tactics is alarming.

"There is no doubt the suicide explosions in Bangladesh pose a serious challenge," says Jaideep Saikia, author of books on terrorism in India and Bangladesh.

"This can destabilise the whole region, the eastern part of South Asia," he told the BBC.

Many have been shocked by the intensity of the recent violence. When police entered the hideout in Moulvibazar district they found a scene of carnage.

"It was a gory sight, unbelievably repelling," said Monirul Islam, chief of the Counter-Terrorism Centre and a veteran of operations against militants. "The militants had blown themselves up along with their wives and children."

Desperation or daring?

The recent suicide blasts began when a woman blew herself up on 24 December to avoid capture during a raid in Dhaka, police said.

Then came the three failed attempts in and around Dhaka.

Alarmed by the suicide explosions, police mounted a series of "proactive operations" across the country.

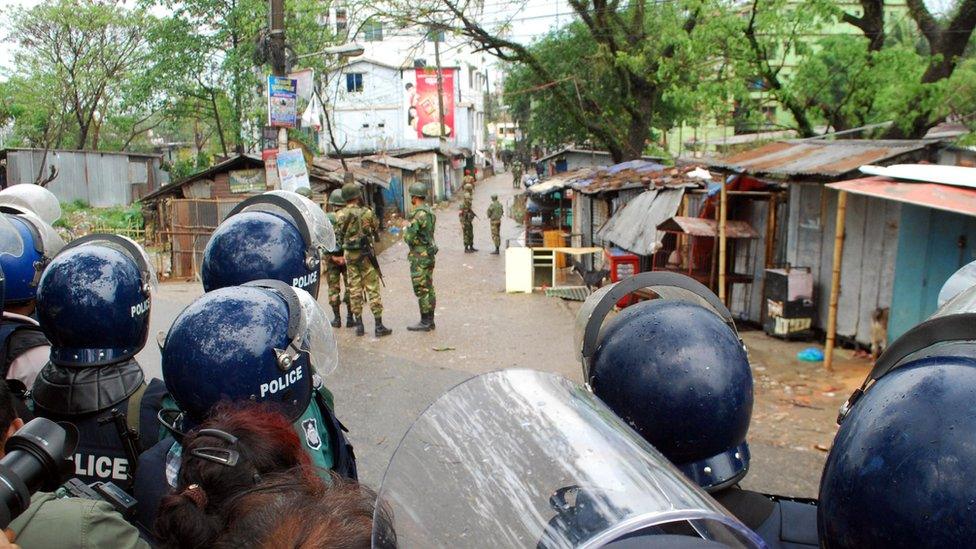

Troops rescued civilians in Sylhet before launching raids on militant hideouts

In Sylhet, they were asked to man the outer perimeter and the army conducted the main assault. Dozens of civilians were freed safely.

But two policemen and the chief of the Rapid Action Battalion's Intelligence wing died, along with four other civilians, when hit by grenades during the assault.

Within hours of the end of the operations in Sylhet, police encircled two hideouts in Moulvibazar and another in the eastern city of Comilla.

Going by recent events, the militants are clearly adopting different tactics.

In Sylhet, they attacked the outer cordon to cause a tactical diversion when the siege was under way.

In Moulvibazar, they blew themselves up to avoid capture - but long before they could inflict casualties on police commandos.

In Comilla, they escaped, taking advantage of city elections which had halted police operations.

"They might have given us the slip," Police Deputy Inspector General Shafikul Islam admitted later.

Opinion is divided on whether the suicide explosions reflect a level of desperation among the Islamist militant groups - or a new level of bravado.

"The militants are now desperate, they are on the run and our police and security forces will continue to hunt them down," said Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal.

"The suicide bombings could be an act of sheer desperation," he said.

The government has consistently rejected claims by so-called Islamic State and al-Qaeda that they are behind the violence, usually blaming an offshoot of the banned home-grown Islamist group Jamiatul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB).

But some remain alarmed.

"There is no room for complacency - terrorism has re-emerged with more vigour," warns Bangladesh-born analyst Taj Hashmi.

And there are persistent worries over the authorities' tactics.

The Bangladesh police and the Rapid Action Battalion have often been blamed, even by the UN, for enforced disappearances, extra-judicial killings and use of torture.

'Our 9/11'

Former diplomat Farooq Sobhan argues that Bangladesh's counter-terrorism efforts have been largely successful so far because the operations have been unrelenting and unwavering.

"But I would now pitch for a more inclusive approach, particularly focused on eliminating conditions conducive to radicalisation," Mr Sobhan said.

The attack on a popular cafe in Dhaka's Gulshan area on 1 July last year led to the massacre of more than 20 hostages, most of them foreigners.

Army commandos were called in after two police officers died trying to fight the militants, all of whom were later killed by the army.

"That was our 9/11, a real hard wake-up call," says Haroon Habib, secretary of the Sector Commanders' Forum, an organisation of veterans of the 1971 war of independence.

Police encountered bloody scenes when they entered a militant hideout in Moulvibazar

The cafe attack came after a series of killings of secular bloggers, writers, publishers, cultural activists and politicians since 2013 that led many to believe Bangladesh was losing its war against militants.

But the Gulshan attack galvanised the country's security architecture into action.

Bangladesh police and paramilitary forces, sometimes supported by the army, went after the Islamist militants with a vengeance.

Between July and December, they say at least eight top militant leaders - such as the JMB's Tamim Choudhury, Tanvir Quaderi and retired Major Zahidul Islam - were killed. Many other alleged senior and middle-ranking activists were arrested or killed in a series of co-ordinated assaults.

Islamist militancy looked like it might have been curbed.

But that is when the suicide attacks began, bringing to Bangladesh the spectre so familiar to the Middle East, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

- Published26 March 2017

- Published28 February 2017

- Published26 July 2016

- Published8 October 2016

- Published24 December 2016

- Published27 August 2016

- Published10 March

- Published5 May 2016