South Korea's 'life or death' presidential election

- Published

Moon Jae-in is the front-runner in the South Korean presidential election

In a room in the National Assembly in Seoul on Wednesday, a group of defectors from North Korea made an impassioned plea to voters: Don't elect the man who has led the opinion polls.

The fugitives from the North said the front-runner, Moon Jae-in, might put their lives at risk if he won the only true opinion poll - the actual election.

The defectors' argument was that Mr Moon was closely involved in a previous left-of-centre government in Seoul which had closer ties with Pyongyang under what was known as the Sunshine Policy.

In a joint statement, the defectors said they had "escaped the slave-like life" under the North Korean regime, and that the re-establishment of more contact with North Korea might mean a return of freer movement between the two halves of the peninsula - with dire consequences for them.

"If candidate Moon Jae-in is elected," their statement said, "a team of North Korean assassins could frequently come to South Korea to kidnap or murder defectors. This poses a life-threatening risk to us."

Their fears show that the election on 9 May is about much more than the mundane matters of economic policy which often dominate elections in democratic countries.

In South Korea, elections are about bread and butter, but also about life and death, peace and war. There is a bigger, global picture with consequences far beyond the divided peninsula.

'Pragmatic approach'

For many South Koreans, the economy remains the dominant issue but, outside the country, relations - or the lack of them - with Pyongyang dominate, particularly when the North Korean nuclear programme is advanced and there's a new brash president in the White House in Washington DC.

Not that Mr Moon says he wants closer ties with Pyongyang.

Rather, he is emphasising close ties with Washington, saying recently: "I believe President [Donald] Trump is more reasonable than he is generally perceived.

"President Trump uses strong rhetoric towards North Korea but, during the election campaign, he also said he could talk over a burger with Kim Jong-un. I am for that kind of pragmatic approach to resolve the North Korean nuclear issue."

Early voting for the election began this week

A president Moon would be unlikely to open direct talks with Kim Jong-un, but he would want a strong and equal role in policy rather than letting Washington call the shots.

He is more likely to favour contact with North Korea rather than the severing of relations undertaken by the previous president of South Korea.

His predecessor Park Geun-hye, for example, closed an industrial complex just inside North Korea where South Korean firms employed workers from the North. A president Moon might re-open it.

Professor John Delury of the Graduate School of International Studies at Yonsei University in Seoul told the BBC: "We know pretty clearly what the presumed front-runner, Moon Jae-in, would do.

"He's supported by people who think the South has to go up there to Pyongyang and actively work on improving inter-Korean relations. If it's Moon who wins this election, South Korea really becomes a new player and could be much more forcefully a part of whatever problem or solution we see on North Korea."

The second in the race is harder to read.

Ahn Cheol-soo is the candidate from the People's Party

Ahn Cheol-soo is likely to be more conciliatory towards Pyongyang than the previous president, though he has been making tougher statements recently, perhaps to woo conservatives.

Either would pose a dilemma for Washington, according to Prof Delury, because they both want to improve the relationship between Seoul and Pyongyang: "And that, of course, flies completely in the face of what the United States is pushing right now which is more sanctions and more pressure and getting China to cut off North Korea.

"So potentially there's a train-wreck here where you've got the Trump administration saying 'pressure, pressure, pressure' on North Korea and suddenly you have a new South Korean president saying 'that's not going to solve the problem - we need to talk to those guys, we need to improve the relationship'."

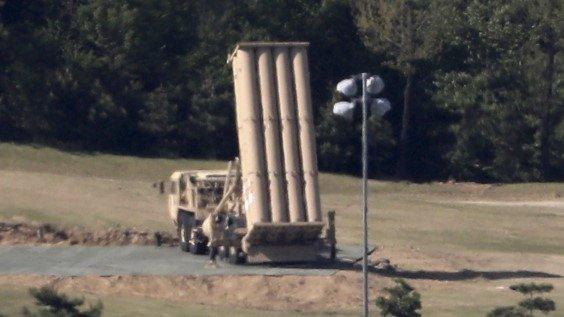

The anti-missile Thaad system has attracted criticism

Despite that, neither candidate - and certainly not the main conservative candidate, Hong Joon-pyo - seems likely to tell the United States to pack up its anti-missile system and take it home.

Thaad, as the system is called, is newly installed on a golf course in the south of the country. Mr Moon has voiced his opposition but whether he would remove it as president is uncertain.

There is opposition to it, both from local people who feel they would be in the line of fire if North Korea attacked the system, and from people on the left who oppose the current hard line against Pyongyang.

'More insecure'

There is a generational divide in South Korean politics. Younger people lack the memory of war - not surprisingly because fighting in the Korean War ended in 1953 - and they feel economic insecurity.

Lee Chae-rin, a student at Yonsei University, told the BBC: "Even though foreigners always ask if we feel the threat of North Korea, the younger generation do not really that much compared with the older generation."

For them economic issues are strong. One of the classmates, Kim Tae-yeon, said: "South Korea has become much richer today but the experience of insecurity is different from that of our grandparents.

"Before, it was a problem of whether they could eat, and that was solved by economic growth. But now we're in a state of economic stagnation and that makes us much more insecure.

"Our problem is not whether we can eat but whether we would lose our function in this society because we cannot find a job."

There is some anger, particularly when the country's former president and the head of Samsung are facing trial for alleged corruption.

Former president Park Geun-hye was impeached over a corruption scandal

One student, Song Seung-hyun, said: "People just want someone who would kick over the table like Trump did in Washington. A lot of these politicians and business elites were in it for themselves.

"It comes down to the youth - our generation - want someone who would kick over the table."

That sentiment may or may not be prevalent in any generation. The winner of the election is not likely to "kick over the table".

They may well, though, want a thawing of relations with Pyongyang.

- Published2 May 2017

- Published6 April 2018