The transgender tailor who died in Saudi custody

- Published

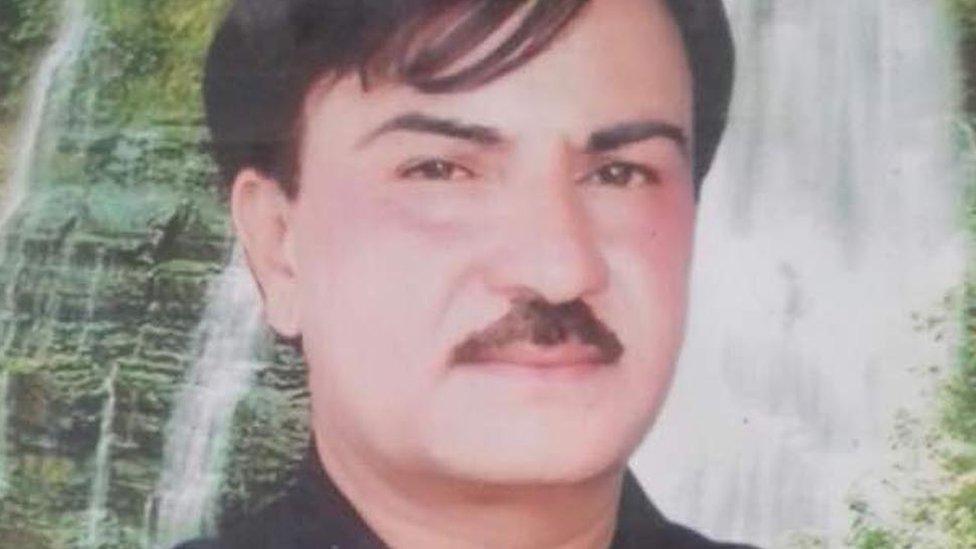

Mohammad Amin, or Meeno, died after being arrested at a party in Saudi Arabia

Mohammad Amin was a family man, with a wife, four sons and five daughters.

But on 26 February, a contingent of Saudi police who broke up a party of transgender Pakistanis in Riyadh found him in women's clothes, wearing jewellery and make-up, and being addressed by others as Meeno Baji - the last name a customary title for an elder sister.

Cross-dressing is not tolerated in Saudi Arabia, so Mohammad and 34 others were rounded up and thrown in Azizia prison.

Mohammad died that night. Pakistani activists say he was beaten by policemen with clubs and hosepipes, causing his chronic heart condition to deteriorate.

The Saudi authorities were quick to deny the allegations of mistreatment, saying he had a heart attack in custody. Pakistani officials followed suit by accusing him of indulging in "illegal and immoral activities".

But Meeno's family, friends and some transgender rights activists paint a different picture of the person, and the events of that last night in Riyadh.

Who was Meeno?

Meeno was born Mohammad Amin in Barikot town in Swat in 1957 to a family of tenant farmers. He had three brothers and four sisters.

At some point during his adolescent years he became a ladies' tailor with a shop in Barikot.

Mohammad Amin worked as a tailor for many years

But unlike most transgender women from Pakistan's rural hinterland who seek anonymity by leaving home, Mohammad stuck with his family.

He married a woman from his tribe in the mid-1980s and a decade later he left for Saudi Arabia on a work visa as a ladies' tailor - a job he held for most of the rest of his life.

We can only guess at his real sexual identity. Social taboos prevent his family and childhood friends from speaking openly.

We know, however, that apart from tailoring, Meeno's favourite pastime was to hang out with the area's trans women who lived together and earned a living by dancing at wedding parties or occasional prostitution.

These activities led to discussions at home.

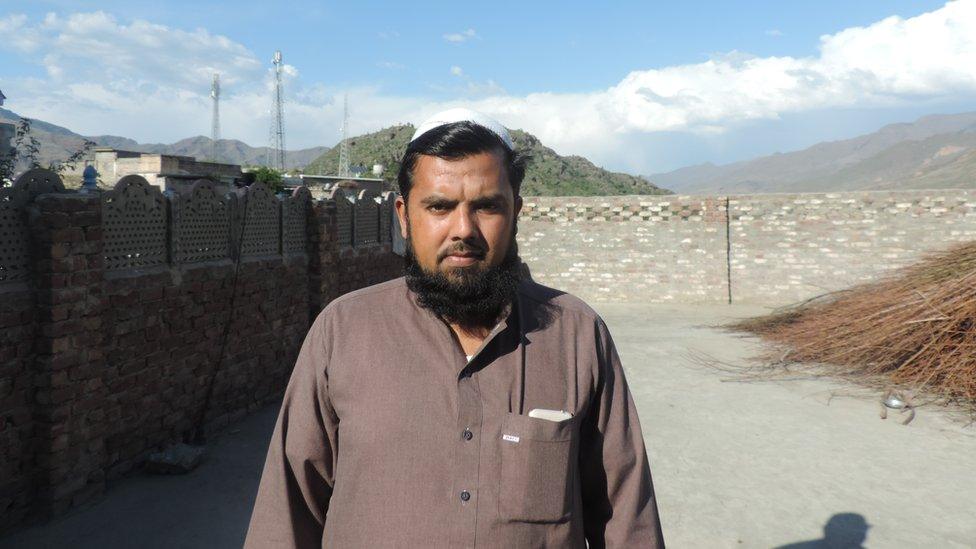

"He was not a 'moorata' [local slang for trans woman], but he did keep their company which created occasional tensions in the family," says his eldest son, Sar Zameen, who is married with children and also works in Saudi Arabia, as a driver.

"His parents and siblings reprimanded him; we, his children, boycotted him for a while; my mother would argue with him often.

"We would tell him that you are giving everyone a bad name; say your prayers. But he would say he couldn't give up his friends. He was not an angry man, but such talk at home often landed him in a bad mood."

Sar Zameen speaks fondly of his father but says parts of his life remain a mystery

Despite this, Sar Zameen remembers his father as a kind and loving person. He put Sar Zameen in an expensive school before he travelled to Saudi Arabia, at a time when he did not have much income.

He also kept the house well supplied, and was often around to offer financial support when relatives or neighbours stumbled on bad luck.

The family's only complaint, says Sar Zameen, was that "he never told us how much money he had, though many of his friends knew".

One of those friends, a local transgender woman called Spogmai (not her real name), shines some light on this.

"Meeno spent a lot of money on looking fresh and attractive," she said.

"She got an expensive facelift done at a clinic in Rawalpindi, and also took a dozen skin-whitening injections. Besides, she had several laser hair removal jobs done on her face and body. She was a beauty."

A long love affair

Farzana Jan, a trans woman who works with a Peshawar-based transgender rights group, Blue Veins, met Meeno in the late 1990s during the latter's first trip home from Saudi Arabia.

Farzana Jan was a dancer then, years before she became a rights activist.

"Meeno came to see me with three other friends. They were in men's clothes but their clean faces, manicured hands and made-up eyebrows gave them away. They were all from rural Swat, mostly tailors.

"They had brought me some gifts. Meeno introduced herself and said Ibrahim Ustad [a locally well-known trans woman who kept an open house for the transgender community in Swat's main city, Mingora] was her guru [guardian, in the transgender community].

"They had heard that there was a new dancer on the Peshawar circuit, and so they had come to see me. They wanted me to dance for them. When they were leaving, Meeno promised that when she came the next time, she would bring me some fine maxi dresses."

Meeno brought Farzana Jan many precious gifts on her subsequent visits, she says.

Farzana Jan, a transgender rights activist, first met Meeno in the late 1990s

Those who knew Meeno more intimately say she had another, more secret life which others could guess at but never found out about for sure.

Spogmai said that Meeno had a 30-year love affair with a man from her native town, until that man died in 2008.

"Gul Bacha [not his real name] was a 'real' man, with a family of his own, but they were both in love with each other," she says.

They went to Saudi Arabia together, and lived together in Riyadh. When Gul died of heart failure in 2008, Meeno accompanied his body to Barikot and then did not return to Saudi Arabia for several years.

A year after Gul's death, Meeno, then 54, was diagnosed with a heart condition, unusual in a family known for longevity.

Spogmai believes Meeno took Gul's loss to heart and that, even though it was not apparent, Meeno's double life was taking its toll on her health.

During those years, Meeno would spend a lot of time with her transgender friends.

"We had a niche for ourselves in a photographer's shop in Barikot bazaar. Or sometimes I would call her over to our place in Mingora," she said.

"All friends would sit together and chat or have singing sessions. Her health had taken away her voice. She could no longer sing as well as she used to, but she would try."

Return to Riyadh

Meeno tried to keep herself busy tailoring clothes at home. Two of her sons were in Saudi Arabia, which meant family money was still coming in.

But then she couldn't take life at home any more - she felt she would be more at peace with herself if she went abroad, says Spogmai. She departed in 2013.

Spogmai says that in Riyadh Meeno tried some relationships, but none succeeded. When she came back to Pakistan on her last trip in the autumn of 2015, she told her friends jokingly: "Your mother remarried, but the guy was not man enough, so we divorced."

She told them there was someone else she had her eye on, though. "She told us, 'your mother will soon marry again'. 'In which lane this time,' we would quip back, suggesting she had a potential lover in every street of the town."

In February 2016, Meeno headed back to Riyadh for what turned out to be the last time.

Farzana Jan, who is popular with the transgender community because of her social work, was kept in the loop by a transgender group who were planning a birthday party for one of the "sisters" at a guesthouse in Riyadh on 26 February 2017.

On 24 February, she received a call. "The birthday girl and another one were planning to adopt Meeno as their mother at the party and there was confusion over rituals. They wanted my advice," she says.

"They were not planning any music or dance, but some of them did wear women's clothing and jewellery and make-up."

Farzana Jan was alerted by text message to the arrests in Riyadh

But then came terrible news. At about 0300 on 27 February, Farzana Jan was awoken by a WhatsApp message from an unidentified caller. It contained a number of pictures of people, some in dresses, their eyes blanked with a pink marker.

"I was puzzled. I replied, asking who this was, and who were the people in those pictures. I then received a voice message stating who the people were and what had happened. I looked at the pictures again, and the faces started to become alive and familiar…"

A Riyadh-based newspaper carried a report of the arrests, but it was Farzana Jan who came out with the claim that the police had tortured everyone at the party and that at least two of them, including Meeno, had been bundled into hessian sacks and beaten with clubs.

According to initial reports provided to Farzana Jan by her contacts in Riyadh, both had died, though no evidence of a second body ever emerged.

Only Meeno's body was shipped back to Pakistan, in the second week of March.

Some transgender rights activists who have been calling for Islamabad to lodge a protest with Riyadh advised Meeno's family to allow a post-mortem of the body in Pakistan but the family refused, thereby foregoing crucial medical evidence.

One of those activists, Qamar Naseem of Blue Veins, received the body at Islamabad airport and says he had a chance to open the casket and look at Meeno's face.

"Her teeth were broken and a part of the torn upper gum was hanging loose in her mouth. I took some pictures of the face."

But in the absence of a post-mortem report, that has not impressed the authorities.

Meanwhile, the Pakistani Senate has responded to pressure from activists to form a committee to liaise with the Saudi authorities and establish how Meeno died.

But few expect a positive outcome - the two states have a "special relationship" that harbours no embarrassing spats over citizen's rights.

The facts of Meeno's death may never fully be known.

But what is clear is she spent her life torn between the necessity of being Mohammad Amin, the husband and father, and an enduring urge to be her other self.

- Published28 June 2016

- Published23 June 2016

- Published18 April 2013