Women's servitude blights Philippine society

- Published

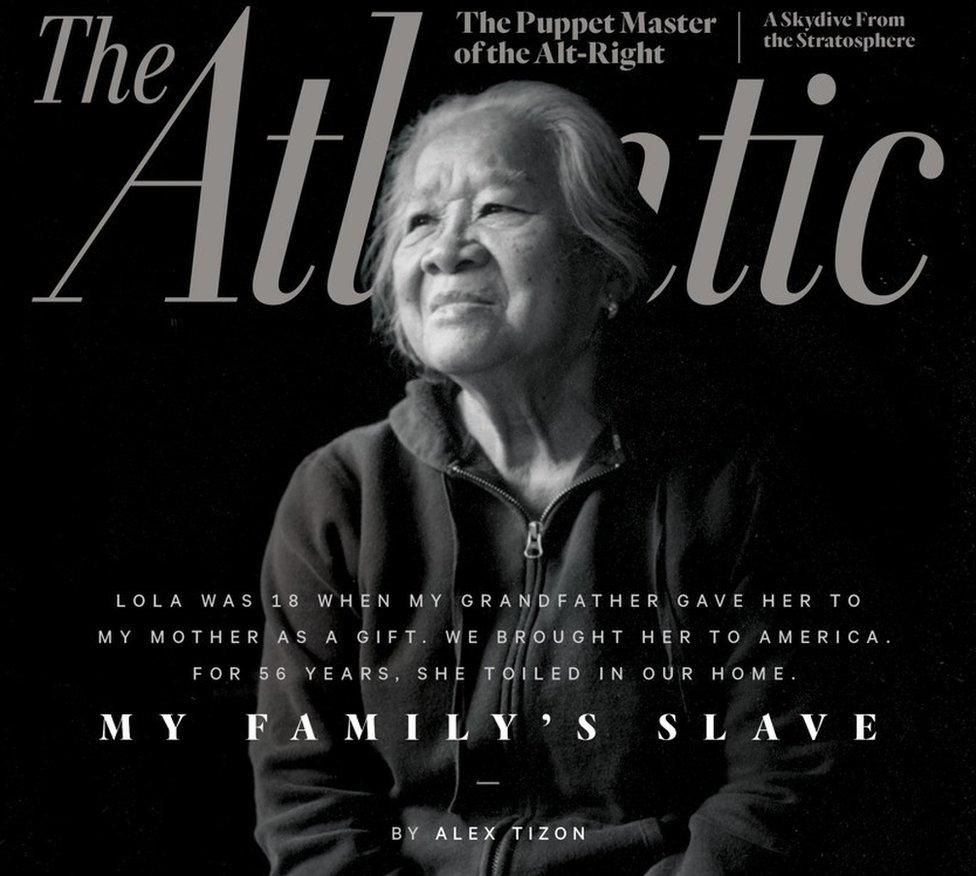

The final article by Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Alex Tizon was controversial when it was published shortly after his death - because it revealed that his family had kept a Filipina slave in the US.

Some readers were appalled, while others leapt to the author's defence. But the core of the story is one that Filipinos relate to - a power dynamic that is deeply rooted in society.

Alex Tizon's A Slave in the Family, external generated a maelstrom. A confessional-memoir, it remembers Eudocia Tomas Pulido, who had been a gift from his grandfather to his mother and who served the family for 56 years - without pay.

Mr Tizon did not evade the issue, naming her a "slave" - though he also called her Lola (grandmother).

The word was a trigger. It named the essence of a servitude familiar to Filipinos, both at home and overseas.

Few have childhood memories without the presence of the caretaker, the yaya, the utusan (the one commanded), katulong (helpmate), kasambahay (home companion) - and now, the industrialized domestic worker.

The name keeps morphing - but the essence of servitude remains the same: a life held hostage.

Americans reacted with a range of emotions to the alien concept

The pre-Hispanic name for the household slave was aliping sagigilid - the gilid embedded in the term means "periphery" or "on the margins" - a precise summing up of the relationship between the served and the one who serves: of the family, but not in the family.

It is a power relationship, indicating the status of the one who serves.

I once referred a Filipina American - who was having cash-flow problems - to house cleaning work for another friend. After a week, she quit. The pay was good, the employer was fine, but she "couldn't stand the power dynamics".

One had to be groomed - by culture, by tradition, by authority - into servitude.

Life in service

Life-long servants are not a rarity in the Philippines. In the multitude of household help in my family, there was always one who stayed.

In 2007, Emma, who had cared for my mother in her final years, said she had been with our family for 40 years. Recruited as a teenager, she had grown up in my younger sister's family, had become a live-out help, married, had children and funnelled nieces and nephews into service with various branches of my clan.

"My family has orbited your family for four decades," she said.

That was the first time I learned her last name.

A trainee works at a housekeeping school in the Philippines, 2013

A full identity is not given those at the periphery. We learn early enough that there is always a woman poorer and more vulnerable who can take on the relentless burden of housekeeping.

I can see a procession of women whose last names I never knew but who served my family: from the reflection in the mirror of myself carried by a yaya (baby caregiver) to the young woman who finally graduated from college and left my employ.

They were invariably browner and from the rural areas, recruited by friends and relations who were landowners. Browner because class and colour do correlate in the Philippines, though this is blithely ignored.

The Spanish-created feudal patriarchal family which persists to this day was a major historical education toward servitude and self-sacrifice. Mr Tizon's grandfather, a landowner, gave Ms Pulido to his daughter as a gift; it was he who administered 12 lashes on Ms Pulido, as punishment for his own daughter's transgression, sealing thereby in the girl's mind the conviction that those who serve must also endure undeserved punishment.

Ms Pulido's enslavement, in the context of millions of Filipinas in domestic work in some 200 countries, hits hard.

'Grooming toward servitude'

The common reason for Filipinas entering servitude is the same siren song used by Mr Tizon's parents to convince Ms Pulido to leave with them: she would be able to build a better house for her parents. The same seductive hope fuels the condominium and subdivision boom in the Philippines.

By April of this year, remittances to the Philippines had reached a record $2.6bn - enough to offset the balance of trade deficit of $2.3bn. According to the Walk Free Foundation, one of two Filipinas working overseas is "unskilled" and "employed as a domestic worker, cleaner or in the service sector".

This persistent devaluing of women's work is a key element in the grooming toward servitude.

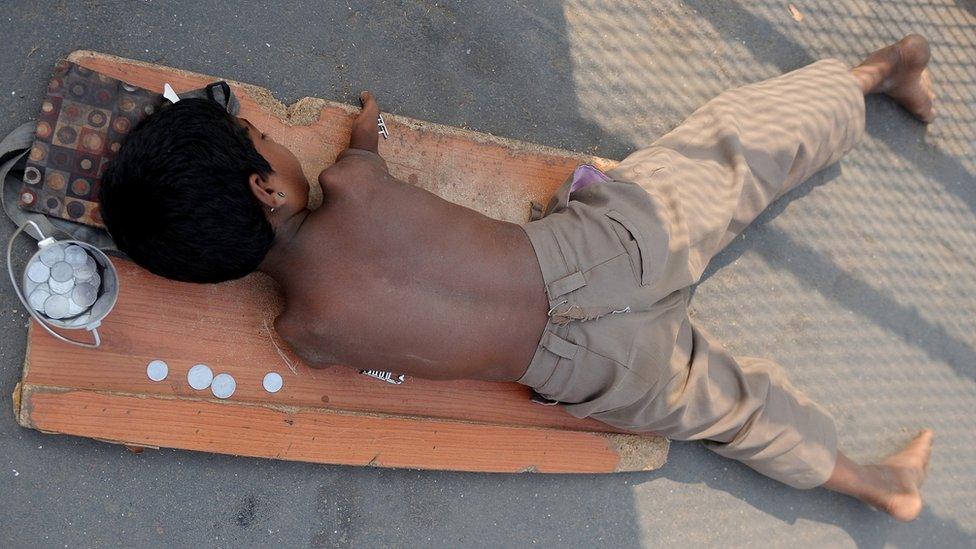

Filipinos are still highly visible in the service industry of many countries

Poverty is, of course, a key to the creation of a category of women whose lives can be held hostage. In China, where the poor make up 8% of the population, women are still associated with marriage, children, family and homemaking. In the same way, a woman with a career in the Philippines still remains responsible for the household, and is the principal nurturer.

While today's options for Filipinas may not be as limited as Ms Pulido's was, her story echoes the irony of fate for millions of Filipinas.

To build a home at home, she has to leave home. She must be indentured to a stranger family, for her own family and the national home to survive.

How to disrupt this relentless demand for self-sacrifice is the question we wrestle with, considering how amply the world rewards selfishness.

Ninotchka Rosca was born and raised in the Philippines, and lives in New York City. She is the author of two novels, and co-founded the women's organization AF3IRM in the United States. She returns to the Philippines regularly.

- Published31 May 2016

- Published28 December 2016