Thailand monks: Wirapol Sukphol case highlights country's Buddhism crisis

- Published

Wirapol Sukphol was seen flying in a private aircraft in a YouTube video released in 2013

It was a jarring image; a group of Buddhist monks, with shaven heads and orange robes, sitting back in the soft-leather seats of an executive jet, passing luxury accessories among themselves.

The video of the monk, now known by his pre-monk name, Wirapol Sukphol, went viral after being posted on YouTube in 2013.

A subsequent investigation by the Thai Department of Special Investigations (DSI) uncovered a lifestyle of what appeared to be mind-blowing decadence. They tracked down at least 200 million Thai baht ($6m; £4.6m) in ten bank accounts, and the purchase of 22 Mercedes Benz cars.

Wirapol had built a mansion in southern California, owned a large and gaudily-decorated house in his home town of Ubon Ratchathani, and had also constructed a giant replica of the famous Emerald Buddha statue in Bangkok's royal palace, which he claimed - falsely, as it turned out - contained nine tonnes of gold.

There was evidence, too, the DSI said, of sexual relationships with a number of women. One woman claimed he had fathered a child with her when she was only 15 years old, a claim the DSI says is supported by DNA analysis.

Wirapol fled to the US. It took four years for the Thai authorities to secure his extradition. He has denied criminal charges of fraud, money laundering and rape.

Monks behaving badly

How had a monk acquired so much influence, even in his early twenties? How was he allowed to behave in ways which clearly violate the patimokkha (the 227 precepts by which monks are supposed to live)? Monks are not even supposed to touch money, and sex is strictly off-limits.

Monks behaving badly are nothing new in Thailand. The temptations of modern life have thrown up many examples of monks with unseemly wealth, monks taking drugs, dancing, enjoying sexual relations with men and women or abusing girls and boys.

There are also temples which have attracted large and dedicated followings, through skilful promotion of charismatic monks and abbots, said to have supernatural powers.

These have capitalised on two aspects of modern Thai life; the yearning for spiritual succour among urban Thais, who no longer have a close relationship with a traditional village temple, and a belief that donating generously to powerful temples will bring success and more material wealth.

It appears Wirapol tapped into this trend. He arrived in the poor North Eastern province of Sisaket in the early 2000s, establishing a monastery on donated land in the village of Ban Yang. But according to the sub-district head, Ittipol Nontha, few local people went to his temple, because they were too poor to offer the kind of donations he expected.

Wirapol was questioned as part of an investigation by the DSI

The monk started holding elaborate ceremonies, he said, selling amulets, and built his replica of the Emerald Buddha, to attract wealthier devotees from other parts of the country.

These followers have described being beguiled by his soft, warm voice, and convinced by his claim to have powers - like the ability to walk on water and talk to deities. In turn, Wirapol gave generously to those with influence in the province; many of the cars he bought were gifts for important monks and officials.

Even today he still has supporters, who argue he is at heart a good man, entitled to enjoy donated luxuries.

Plagued by scandals

After a succession of scandals, people are openly talking about a crisis of Buddhism in Thailand. Numbers of ordained monks have been falling steeply in recent years, and many smaller village temples are unable to support themselves financially.

The body which is supposed to govern the Buddhist clergy is the Supreme Sangha Council, but this comprises a group of very elderly monks, and until this year had not had a properly functioning Supreme Patriarch for more than a decade. It has proved ineffective.

The National Office of Buddhism is also supposed to regulate the religion, but it too has been plagued by leadership turmoil and allegations of financial irregularities.

The government has now introduced a law requiring temples, which collectively accumulate $3-4bn (£2-3bn) in donations every year, to publicise their financial records. It is also talking about introducing a new, digital ID card for monks to ensure those tainted by malpractice cannot be ordained again.

The faltering morality of monks, though, is partly rooted in the way Buddhism has evolved in Thailand.

For 150 years there have been two quite different forms of Buddhism; that of the more austere, Thammayut tradition, practised in the elite, palace-backed temples of Bangkok, which upholds the strict rules about monks detaching themselves from the material world; and the looser Mahanikai tradition of the provinces, where monks are part of the community, joining neighbourhood activities, sometimes in violation of the patimokkhai.

In the villages, temples have served as schools or traditional centres of medicine and venues for local celebrations. The advice of monks has been sought on a range of worldly issues; in this environment the line between what is and is not acceptable behaviour can become blurred.

'Building cases against themselves'

The other source of the problem is the hold that superstition has over many Thais, and the way this has become commercialised.

Monks are these days often used more as deliverers of semi-religious rituals - like blessing new cars or houses for good luck - than practitioners of the 227 precepts. No-one in Thailand bats an eyelid at the sight of lottery tickets being sold inside temples.

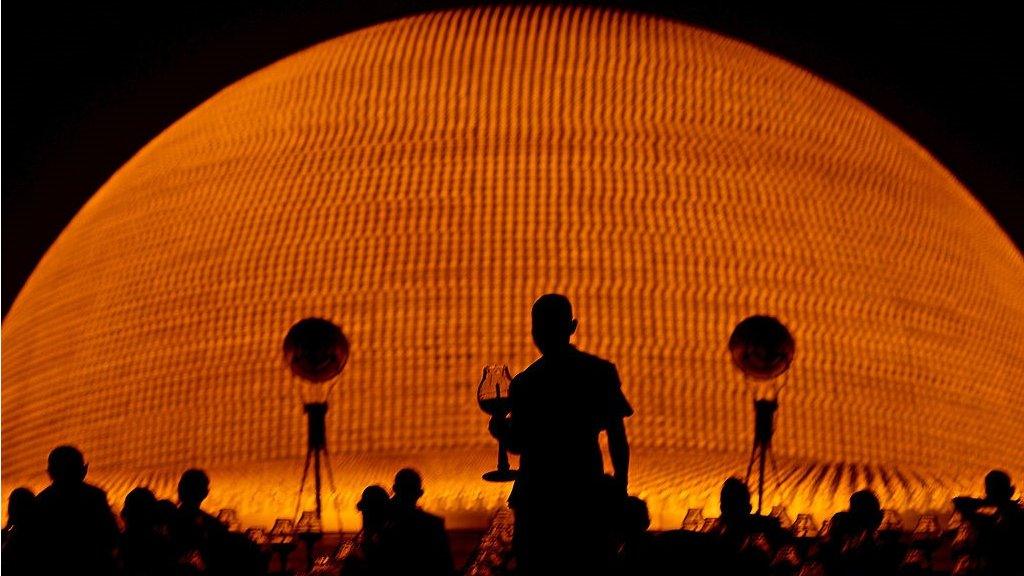

Buddhist monks are not supposed to touch money, and sex is strictly off-limits

This love of superstition extends to rich Thais, who are happy to donate generously in the belief this will ensure greater fortune in the future.

Phra Payom Kalayano, the abbot of a temple north of Bangkok well known for his criticism of the commercialisation of Buddhism, has appealed to Thais to be more thoughtful about donating.

"Nowadays people think good karma is about throwing money at temples - especially rich people. They have faith, but they don't think. That is not practising good karma, smartly. That is just blind faith.

"At the same time, some monks are stupid. They don't know how to manage the donations they receive. Instead of managing the money to build karma and prestige for the temple, the monks end up building criminal cases against themselves," he said.

In a simpler age, before the arrival of globalisation and its many consumer distractions, it was easier to advocate a monastic life that disavows all material pleasures. But it is harder today to insist that monks should forego technological conveniences like smartphones and air travel.

It is even harder to define what role monks should play in 21st Century Thailand, beyond the provision of services like amulets and good luck blessings, which can so easily turn into a money-making business.

- Published20 July 2017

- Published22 March 2017